Family : Delphinidae

Text © Andrea Tarallo

English translation by Mario Beltramini

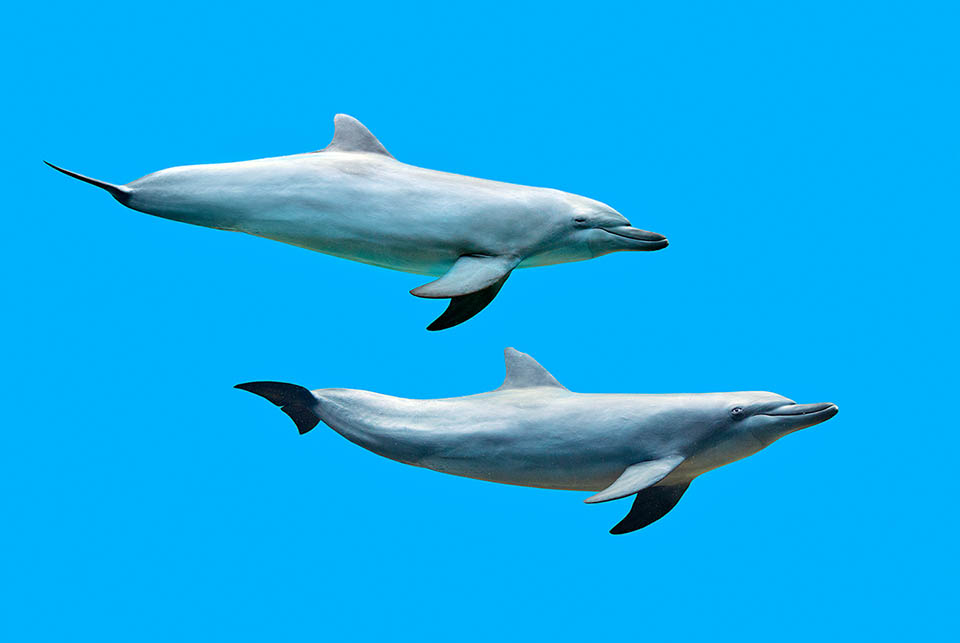

Present in Indo-Pacific, from East Africa to Taiwan up to the eastern coasts of Australia, Tursiops aduncus is a dolphin that loves warm waters, with 20-30 °C on the surface © Giuseppe Mazza

The genus Tursiops is probably the most known and the most studied among the cetaceans, and is the protagonist of the legends of ancient Greece and of ancient Rome. It is described already by Aristotle, Oppian of Anazarbus and by Pliny the Elder.

This because till the end of the nineties the genus Tursiops inclu- ded only the Common bottlenose dolphin, Tursiops truncatus, that has a practically cosmopolitan distribution, excepting the polar zones. Moreover, among the most common cetaceans, it is the species that prefers more the coastal waters, unlike the common dolphin and those of the genus Stenella which prefer pelagic waters. This has probably contributed in facilitating its study and observation.

Owing to the vast distribution range of the described subspecies, only on a morphological basis, were considered as simple regional variants of the same species. It has been then proved, thanks mainly to molecular proves, besides osteological and morphological studies, that the Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops aduncus Ehrenberg, 1833) is a real species reproductively isolated. Recently, it has been addes a third species endemic to the coastal waters of southern Australia: Tursiops australis Charlton-Robb et al. (2011). It is not to be excluded that an expansion of this kind of studies leads to a broadening of the genus.

Smaller than the almost cosmopolitan Tursiops truncatus, also present in its range, the Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin reaches 200 kg and about 2.7 m in length © Giuseppe Mazza

The name “tursiops” can be translated as “similar to a dolphin”, in fact “tursio” in Latin rightly means dolphin, while the suffix “-ops” comes from the Greek, and means look, appearance. Also “aduncus” is of Latin derivation and means “hooklike”, specific name probably due to the fact that the jaw on this species is slightly bent upward. The dolphins belong to the class Mammalia, order Cetacea, suborder Odontoceti, that is, the cetaceans with “true” teeth, family Delphinidae.

Zoogeography

The Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin has a distribution limited to the coastal waters of the Indian Ocean and of the western Pacific one, from East Africa to Taiwan, up to the eastern coasts of Australia.

Ecology-Habitat

Usually the species of bottlenose dolphins prefer the coastal waters, in areas with high productivity, such as rocky or coral reef, the prairies of marine plants and the estuaries.

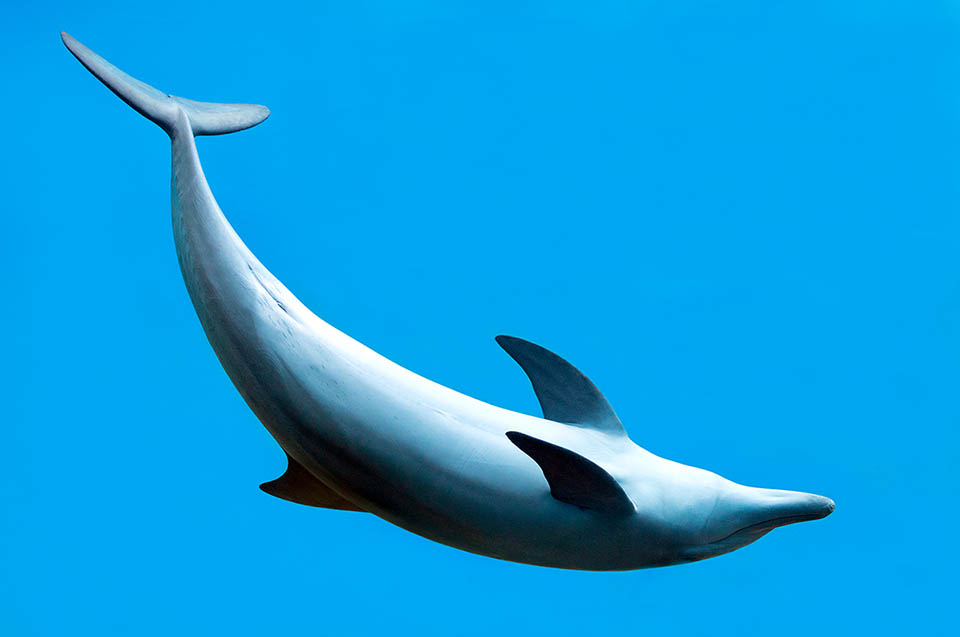

A skilled swimmer, it appears slimmer due to its long, thin snout with proportionally larger fins and rostrum © Giuseppe Mazza

Have also been reported movements at great depths, but it is not known if this type of behaviour is common in Tursiops aduncus.

Mainly, this species loves the warm waters, being the temperatures recorded at the surface included between the 20 and the 30 °C. The ample range of temperatures varies a lot also due to the vast distribution of the species and the lowest recorded temperature is of 12 C, in the Japanese waters.

Tursiops aduncus has a superimposable distribution with many other species of cetaceans, and are recorded often cases of mixed groups of species swimming together. The degree of heterogeneity of the groups at times varies regionally: for instance in the waters west to Taiwan, despite the presence of the Sousa chinensis, it has never been observed a mixed group of the two species.

There is a lot of geographical variability also in the diet. The main preys of the Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin are demersal or reef fishes and cephalopods, but does not disdain the hunting to pelagic and epipelagic species, usually of small size.

Predated by sharks, it eats fishes and cephalopods, hunted on the seabed or in open seas © Giuseppe Mazza

In some zones, the level of specificity of the predation may be very high, with two or three species neatly dominating the others as choice. For observations in captivity it seems that the necessity of alimentation is of about the daily 4-5% of the body mass, but tends to increase with the lowering of the temperature.

Little is known about the predators of this species, but in most cases the sharks appear to be the main cause of death of dolphins in nature, except man, especially the tiger shark, white shark, sand tiger shark and the dusky shark.

For some populations the probability of attack is very high, more than the 70%. They are not predated by killer whales which however attack often other marine mammals. They are affected by external parasites (cirripeds and amphipods) and internal (roundworms and tapeworms), but probably less affected than other cetaceans.

Morpho-physiology

Like all cetaceans, dolphins are mammals adapted to the sealife. Consequently, though maintaining some characteristics typical of the terrestrial cousins, their external look has modified to adapt to the aquatic life until they looked like fishes. This phenomenon is called convergent evolution.

The body in fact is characterized by a fusiform shape, head with a “beak”, the rostrum, equipped with homodont teeth, that is, all the same. They have no external ears and have one single bowhole, on the top, for breathing, which, obviously, is aerial. The pectoral appendages are transformed in fins, the pelvic ones have gone lost. The tail has no bony structures apart the vertebrae, as well as the dorsal one, and consists in two symmetrical lobes placed on the frontal plane (horizontal) and not sagittal like in the fishes.

For what concerns the specific morphology of Tursiops aduncus, this is usually smaller than the cousin Tursiops truncatus, reaching at most the 200 kg of weight and a length of about 2,7 m. In some populations the maximum length is even minor.

In respect to Tursiops truncatus the appendages (dorsal fin, pectoral fins and tail) are proportionally bigger. Also the rostrum is proportionally bigger in Tursiops aduncus, the snout is longer and thinner, the melon (the adipose organ placed between the rostrum and bowhole responsible of the echolocation) is less bulbous, and the head has a more pointed profile. This helps to give a more slender look to the species.

Very intelligent animal, has changeable social relations with units joining and leaving the group. Males and females associate in monosexual groups, the first to compete with other males groups for the access to the females and entrap them for reproduction, the females instead for defense against too aggressive males © Giuseppe Mazza

The eye region appears laterally swollen if seen from above. The pigmentation is rather simple, from darker grey on the dorsal surface gets paler on the sides, at times with a quite neat break. The abdomen is whitish, often with nuances tending to pink.

In Tursiops aduncus is peculiar the presence of dark maculae on the ventral part. Even if usually the shape and the distribution of these small spots is similar among the subpopulations, several regional variabilities and even individual ones are recognizable, whereas some individuals may show also some spots on the dorsal part.

The pattern of spots can be utilized for recognizing the individuals. The intensity and the specificity of the presence on the body of this particular drawing begins with the achievement of the sexual maturity and increases in intensity with the age, and we may also try to estimate an approximative age by evaluating the level of pigmentation of the maculae. Also the perimetre of the mouth and the tip of the rostrum tend to turn white with the age. The young, conversely, have usually a paler pigmentation and have no maculae.

A mating. After 12 months of gestation, females give birth, usually in spring or summer, to a young of about 1 m © Cordenos Thierry

Ethology-Reproductive Biology

The sexual maturity is achieved between the 7 and the 15 years, but also this character probably varies on regional basis, and the females tend to mature earlier than the males. The fecundation is internal. After 12 months of pregnancy, the female delivers, usually in spring or summer, an about one metre calf.

This also means that the peak of births coincides also with the peak of matings. The mortality of the calves is high during the first three years of life, period in which they do not leave the mother. Studies on dolphins in captivity report an 18 months long breastfeeding, but studies on the field report periods long even the double, an indeed remarkable maternal investment. In some areas the males are little bigger than the females, but apart this there is not a real sexual dimorphism.

The life span is of about 50 years. The societies of the cetaceanas are traditionally considered as very complex, seen also the great volume of their brain, and the odontocetes develop societies more complex than the mysticetes.

Mother with calf. In captivity it is breastfed for 18 months and about double at sea, where it can reach 50 years of age © טל שמע

In the case of the Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin we talk of societies of fusion-fission (fusion and division) rightly because their composition varies even very fast in the time, with individuals who become part of the group, and others that go away. The associations in groups have variable size, often even mixed as we have already briefly said, but always very flexible. Usually, during the day the groups are very small, maybe to facilitate the huntings, and then gather in larger groups towards evening, probably to better defend themselves from the attacks of the sharks.

Males as well as females associate in monosexual groups, the first ones to compete with other groups of males for getting the access to the females and to entrap the groups of females for reproductive purposes, the females, on the contrary, for defending themselves from too aggressive males.

Population trends are little known and since 2019 Tursiops truncatus has been listed as “NT, Near Threatened“ on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species.

Synonyms

Delphinus aduncus Ehrenberg 1832.