The false petals that seduce insects. History and sexual life of these strange South African flowers. How to cultivate these plants in our climates. Hybridization and selection in the Côte d’Azur.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

The evolution of the plants, and of life too, generally speaking, does never proceed on a straight line, but spirally, and nature often invents something new, while following tracks already beaten.

Time ago, in the Green World, the sexes were separated. It’s the case, for instance, of the conifers, archaic plants, which, still now, show well distinct reproductive structures.

Small and numerous masculine cones, to produce the pollen, and feminine cones, the pine-cones, which swell, once the fecundation has taken place, to protect the seeds.

A valid scheme, after all, seen that it has come, unchanged, to our times, but with an Achilles’ heel: the pollination is entrusted to the wind, and, in order to reproduce, fir-trees and pines are obliged to live, side by side, in thick groups.

For this reason, at the shade of a prehistoric pine, a tropical “out of fashion” species, had, long time ago, a lucky intuition: instead of building the usual pine-cone, it created something showy, the flower, to attract the birds, “postmen of pollen”, much more reliable than the wind. The corolla, large and coloured, was well visible from far away, and the two sexes, united in a unique structure, allowed, at each visit of the guest, the withdrawal and the delivery of the pollen.

But also this strategy, which triumphed for millennia, had its weak points. First of all, the birds are intrusive partners, which, not satisfied of the nectar, eat often, without any scruples, the petals and the ovaries, the precious nurseries of the plant; and, then, are reliable at the Tropics only, where there is food all the year round.

In the cold climates, when the vegetative season is short, they come often too late, and they are not always around. So, to some storm plants, which were leaving for conquering the temperate areas, came the idea to exploit the insects. That was the rush to the miniaturization of the corollas, with gentle scents and structures suitable to the new pollen carriers. The front flowers became smaller and smaller, so much small, that, at a certain moment, also the insects could not see them any more.

The nature was again at a turning point. And to some plants, maybe the ancestors of the daisies, came the idea to gather together their tiny corollas in big bunches, the heads, to imitate in a sort of mosaic, the showy flowers of the past times.

What was good in the conifers civilization?

The clear separation of the sexes, the best method to avoid incests, and the cone-shaped structure which protects the seeds.

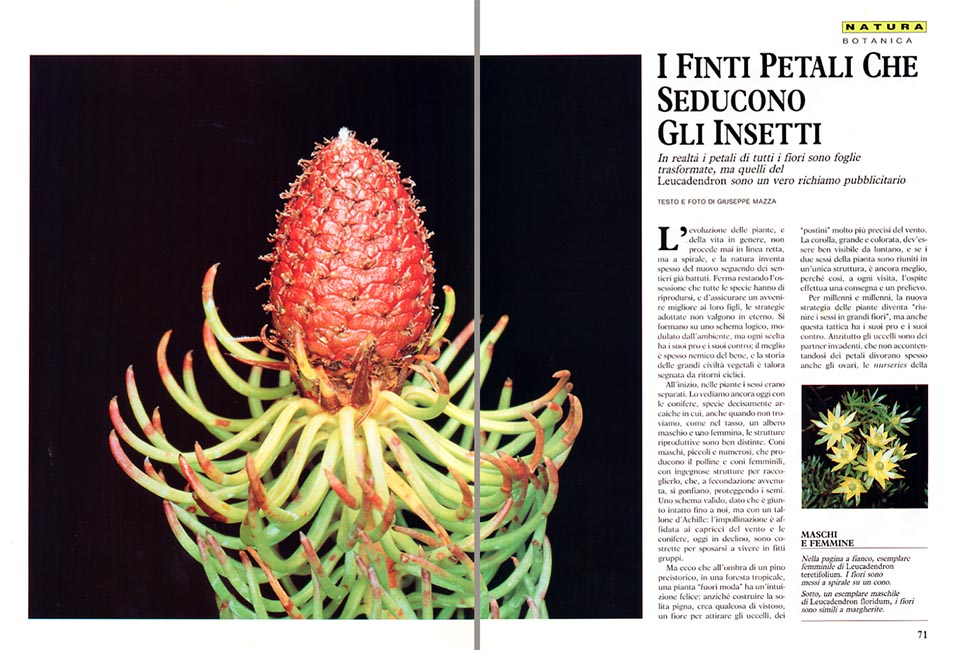

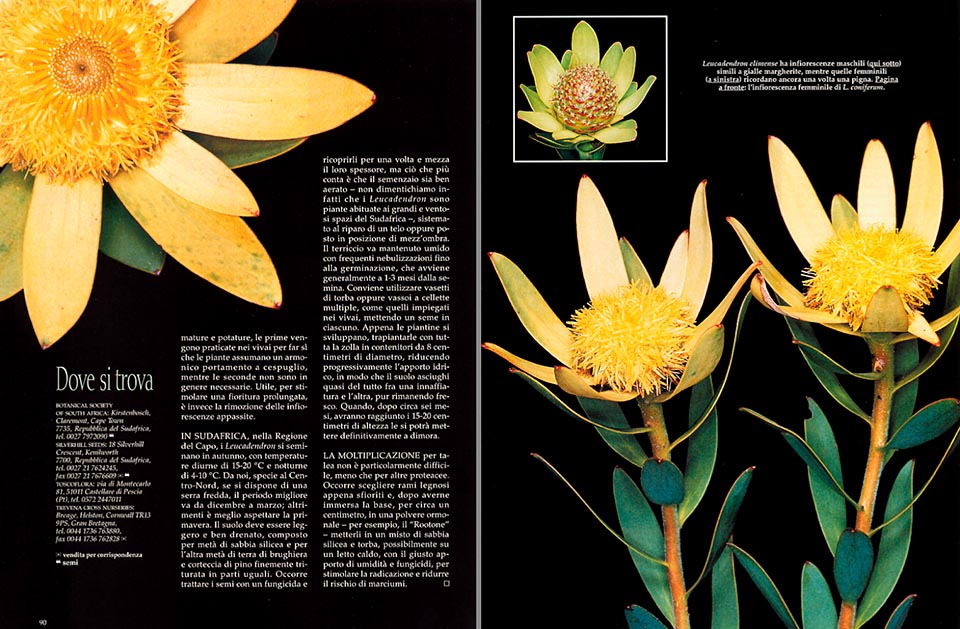

And the Leucadendron have taken possession of these intuitions. After having miniaturized the corollas, and having understood that union is strength, they decided to produce in some plants only male inflorescences, and, in others, female ones only, similar to cones.

And not all were at variance about the choice of the “postmen”.

Some “extremists”, nostalgic of the past, were resolutely favourable to the wind; but the “moderates” were thinking that, after all, the alliance with the insects was not too bad, and that it was more convenient to count on a rich nectar, perhaps crystallized, in lumps.

It is difficult to say who was the winner, probably, the last ones, seen that, nowadays, of the 79 species of Leucadendron, 4 have opted for the anemophilous pollination, and 75 for an abundant condensed nectar.

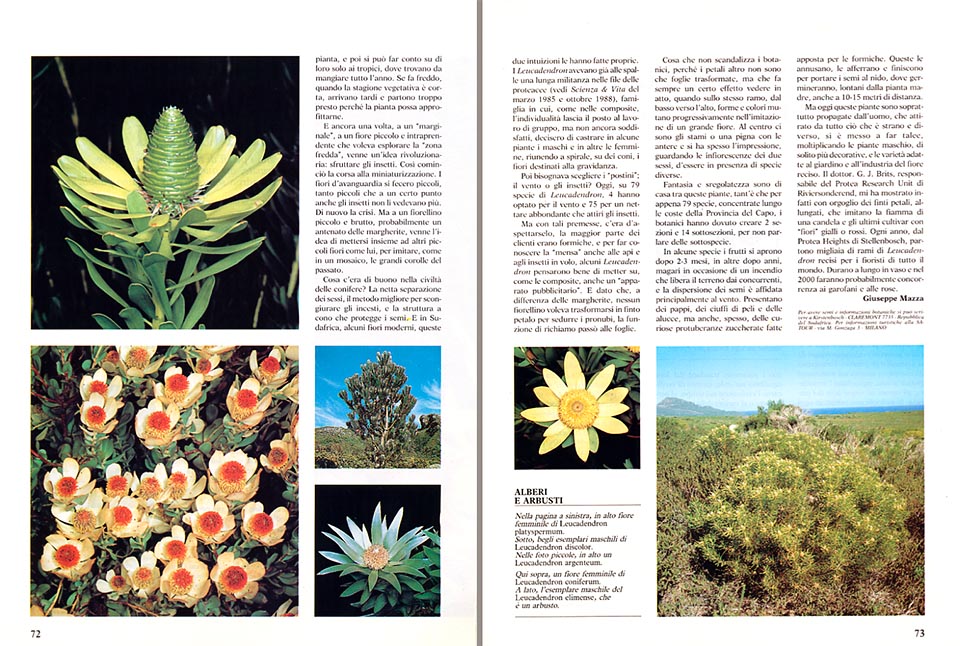

Most of the pollinators are ants; but, in order to multiply the chances of reproduction, some species have built, like the asteraceae, also a major advertising apparatus meant for the flying insects, with flowers disposed like petals, thus creating flowers with an unusual look, often very different, depending on the sex, also in the same species.

Inflorescences like big daisies and anemones, but also “green hallucinations”, with cones, bright and sticky, like jam, or velvety and almost spherical like the globose fruits of the cypresses.

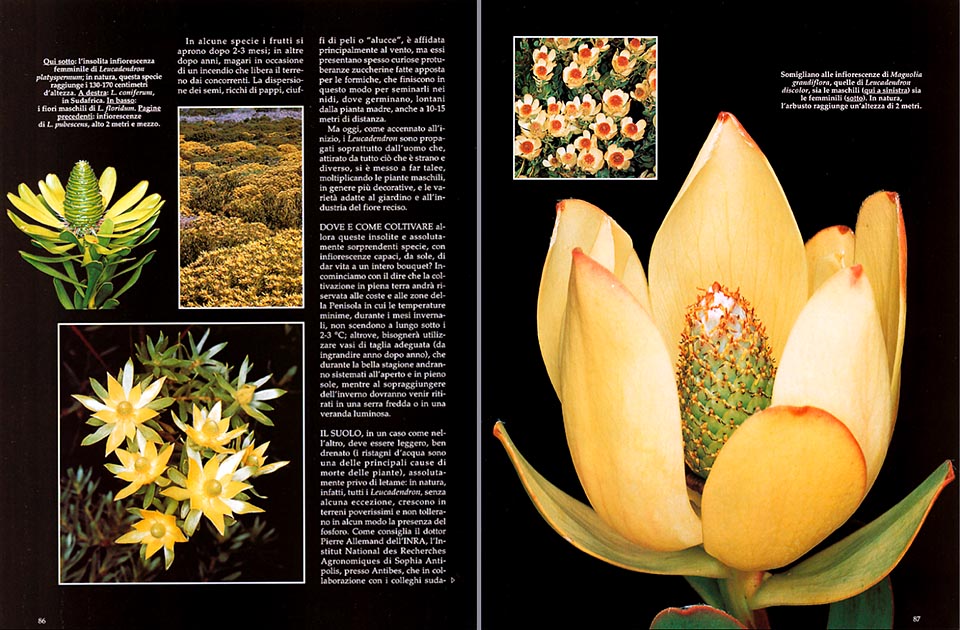

Shrubs often united in wide waving extents, but also 10 metres tall plants, such as the Silver leaf tree (Leucadendron argenteum), one of the most rare and elegant in the world.

In some species, the fruits open after 2-3 months; in others, after years, maybe after a fore which has freed the soil from the competitors.

The scattering of the seeds, rich of pappi, wisps of hair, or small wings, is entrusted mainly to the wind, but they present often funny sugary protuberances made expressly for the ants, which, in this way, end up in sowing them in the nests, where they can germinate, far away from the mother plant, even at a distance of 10-15 metres.

But nowadays, the Leucadendron are mostly propagated by the man, who, attracted by all what is strange and different, has started to do cuttings, multiplying the masculine plants, usually more ornamental, and the varieties suitable for the garden and for the industry of cut flowers.

Dr. G.J Brits, in charge of the Protea Research Unit of Riversonderend, shows me, proudly, some fake, prolonged, petals which imitate the flame of a candle, and the last cultivars, with yellow or red “flowers”. Every year, from Protea Heights of Stellenbosch, leave thousands of cut branches of Leucadendron for the florists of all the world. When in vase, they last long time, and they are already competing with the carnations and the roses.

CULTIVATION

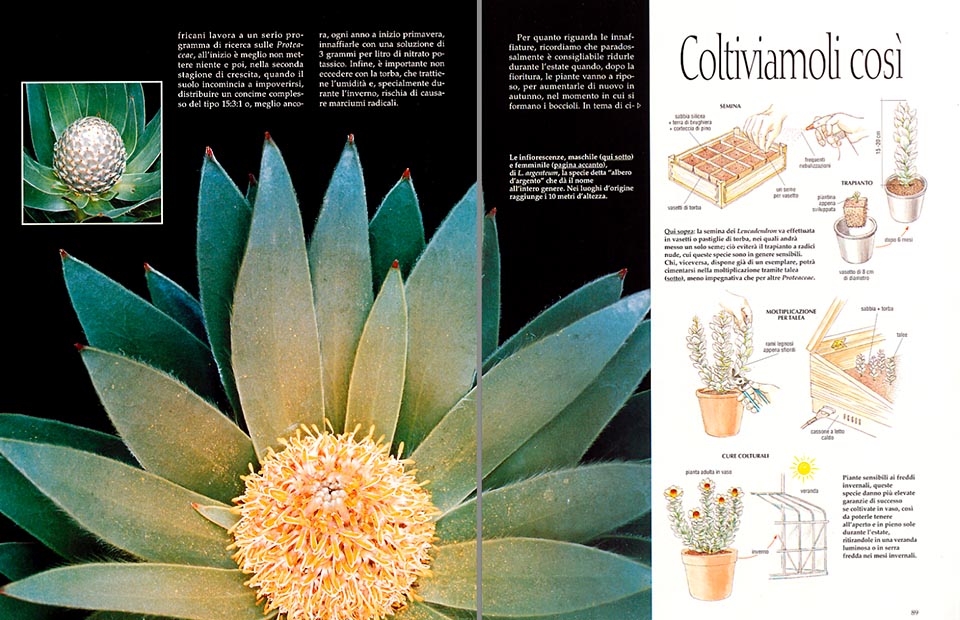

In South Africa, in the Cape Province, the Leucadendron are sown in autumn, with day-time temperatures of 15-20 °C, and 4-10 °C, during the night.

In our countries, in the warm Mediterranean climates, in cold greenhouse, the best period goes from December to March. Otherwise, it is better to wait for the spring.

The soil must be light and well drained, composed for a half of siliceous sand, and, for the rest, in equal parts, of land of moor and bark of pine finely ground. It is necessary to treat the seeds with a fungicide and to cover them for one and a half times their thickness; but, first of all, the seed-bed must be well ventilated, sheltered by a curtain pr in mid-shade positions.

The compound must be kept wet with frequent nebulizations till the germination, which usually happens 1-3 months after seeding.

Usually, it is convenient to place one seed per box in the plaques with cavities on the market; and, as soon as the small plants develop, to transport them with the whole sod in small 8 cm pots, reducing progressively the water input in such a way that the soil dries up almost completely, even if remaining cool, between the various watering.

When, after six months, they have reached the height of 15-20 cm, they can be settled in place in the garden, or in pots of adequate size, for embellishing terraces and bright verandas, where, in any case, they must be placed during the winter, when the lowest temperatures remain for long time under the 2-3 °C.

The multiplication by cutting is not difficult. We have to choose some woody branches just withered, and after having dipped them at the base, for about one centimetre, in a special hormonal powder, the “Rootone”, they must be placed in a mixture of siliceous sand and peat, possibly on a warm bed, with the right input of humidity and fungicides, in order to stimulate the rooting and reduce the risk of rottenness.

All Leucadendron love the sun, the wind, and the soils well drained, but without dung. In the wild, they grow up, in fact, in very poor soils and do not absolutely tolerate the presence of phosphorus.

It is better, at the beginning, not to put anything, and then, sugegsts Dr. Pierre Allemand of INRA, the Institut National des Recherches Agronomiques of Sophia Antipolis, which carries on, in cooperation with some South African colleagues, a serious research programme on the Proteaceae, it is good practice to put a manure of the type 15, 3, 1 or, even better, to water the plants, at the beginning of the vegetative season, with a solution of three grams per litre of potassium nitrate.

Better, also, not to exceed with the peat, which holds the humidity and, particularly in winter, can cause rottenness to the roots.

SCIENZA & VITA NATURA – GARDENIA – 1990