Family : Syngnathidae

Text © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

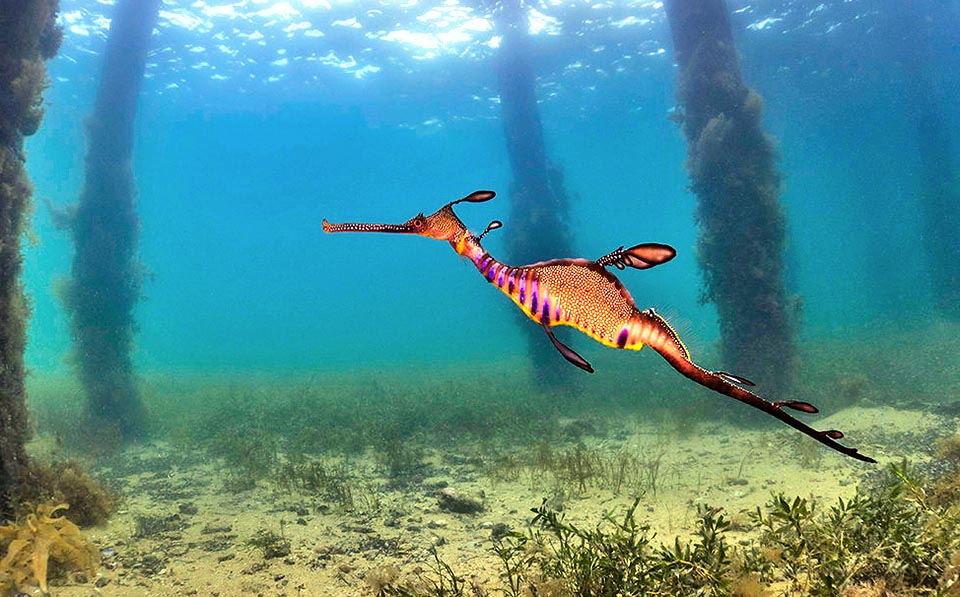

The Common seadragon (Phyllopteryx taeniolatus), here in a seagrass meadow of the genus Amphibolis, lives in temperate waters between South Australia and Tasmania © Paddy Ryan

Called Common seadragon or Weedy Seadragon, Phyllopteryx taeniolatus (Lacepède, 1804), is not an oceanic monster but a harmless and unusual species belonging to the class of Actinopterygii, the ray-finned fishes, to the order of Syngnathiformes and to the family of Syngnathidae, that of the pipefishes and of the seahorses, that groups more than 300 species often present also in the brackish waters of the estuaries with some members in the fresh waters.

The genus Phyllopteryx comes from the old Greek “φύλλον” (phyllon), leaf and “πτέρυξ” (pteryx), meaning feather, wing because of the mimetic appendages, similar to leaves, it has on the body.

Here in the majestic scenery of a bottom with giant columnar weeds of the genus Macrocystis. It can go down up to 50 m, but is often found also in the surface waters © Rafi Amar

The specific term taeniolatus comes from the Latin “taenis”, ribbon, and therefore “with small ribbons”, evoking the violaceous vertical bars of its livery.

Zoogeography

Phyllopteryx taeniolatus is endemic to southern Australia: from Geraldton, on Western Australia, to Tasmania and Port Stephens in New South Wales.

30-32 cm long, with a record to 46 cm, belongs to the family of seahorses. Here looks for microscopic crustaceans among the algae of the genus Ecklonia © John Turnbull

Ecology-Habitat

It is mainly found between 8 and 20 m of depth, but is often present in very shallow waters and has been sighted even at 50 m. It does not live in tropical waters but in temperate ones, in climates similar to the Mediterranean with temperatures standing between 12 and 23 °C.

It frequents the seagrass meadows of the genus Posidonia and Amphibolis, and various species of algae, with a predilection for the tufts of Ecklonia ovalis and Ecklonia radiata, the expanses of the genus Amphibolis and the suggestive columnar structures of Macrocystis pyrifera and Macrocystis angustifolia. All with fronds rich in the microscopic crustaceans it feeds, belonging mostly to the order Mysida.

It sucks them whole, like the seahorses, with its very long snout. Also here the scaleless body, taller in the females, is armoured under skin by bony plates. Has no prehensile tail but big cutaneous appendages like leaves and a fanciful mimetic livery transforming it in a fragment of a drifting withered weed © John Turnbull

When it is associated with floating weeds such as the dargassoes it can be found offshore or ended up beached and the sea storms often make massacres of those navigating on the surface throwing them on the coasts. In fact, the Common seadragon is a very bad swimmer and cannot anchor to the bottom like the seahorses because its tail is not prehensile.

Morphophysiology

Phyllopteryx taeniolatus does not exceed the length of 46 cm, with an average size of 30-32 cm.

Male, often darker, is much slender than female. Swimming is entrusted to the modest dorsal fin and stabilized by two small pectorals placed close the head © Rafi Amar

Like the seahorses, it has no scales but is armoured under the skin by bony plates and has small defensive spines along the body with two, more showy, placed at protection of the eyes.

The snout is long and cylindrical, born from jaws welded together as happens with all the Syngnathiformes, apart from the adults of the genus Bulbonaricus that, like Bulbonaricus brauni, lose it during their growth.

But with respect to the seahorses, it is a very long snout, so much that when looking in profile together with the head evokes the shape of a pipe.

A couple. The long courting dance lasts 2-4 weeks. When male is ready it curls the tail and the female pastes on it even 250 ova, immediately fecundated © John Turnbull

Also here is present a suction mechanism because the mouth has no teeth, and the small prey are gulped down whole.

The locomotion is entrusted to the modest dorsal fin, longer than the seahorse but equally low. Transparent and almost invisible ii arranged at the beginning of the tail in a very backward position, whilst the small pectoral fins, placed close to the head, serve to maintain the balance and when maneuvering. The caudal and the pelvic fins are missing, but on the ventral side we note two showy symmetrical appendages similar to leaves, like those placed like a handlebar at the apex of the back, where we could expect to find a fin.

The glue stimulates the skin of the male forming some vascularized small cells © Rafi Amar

Another isolated sail is present on the head and one on the neck, whilst the others, in pairs, always smaller, follow each other towards the tip of the tail.

The shape of the body is not less surprising like the fanciful mimetic livery. The background colour, usually reddish brown or with orange shades, is studded with small yellow spots that continue on the snout and towards the head we note the 7 characteristic violaceous vertical bands that have given the name to the species.

When it moves the predators confuse it for a tuft of wandering algae and in the meantime it surprises, without being seen, the small crustaceans and the larvae of the fishes that are part of its diet.

The males, darker and much slender than females, have during the reproductive period a vascularized structure under the tail with small separate cells for the incubation of the eggs, as occurs, in ventral position, for the pipefishes, for instance, Dunckerocampus dactyliophorus.

Phyllopteryx taeniolatus does not have subspecies but in the same range goes around a close relative, the Leafy seadragon (Phycodurus eques), quite similar and at times confused, with more abundant and developed foliar appendages.

Ethology-Reproductive biology

The Common seadragon lives solitary or in pairs nourishing almost non-stop, because, like the seahorses, it does not have a stomach and its fast intestinal digestion is little efficient.

It reaches the sexual maturity when about 30-32 cm long and the reproductive period, that begins when the temperature of the water exceeds 14 °C goes from spring to late summer.

The very long courtships last 2-4 weeks.

Thus, every embryo is fed, besides the yolk, by the blood capillaries of male that carry, at the same time, also the oxygenation necessary for their development © Rafi Amar

The partners go swimming together in a sort of a dance and when the male is ready for mating it signals it by curling the tail.

Then the female lays there even 250 ova, immediately fecundated, covered by a sticky substance that keeps them stuck to the skin stimulating the formation of the small cells.

Thus, the embryos grow up nourished by the yolk and by the paternal blood that furnishes also the oxygenation necessary for their development.

Usually, the gestation lasts 30-38 days and the male takes the brood for a walk protecting it from predators © John Turnbull

Usually, the gestation lasts 30-38 days and when just born the kids predate copepods and rotifers. In turn they are threatened by the sea anemones who eat almost half of them, but the resilience of the species is good with a possible doubling of the populations in less than 15 months and a vulnerability index linked to the fishing that marks nowadays, in 2022, just 24 on a scale of 100.

In fact, it is not a species threatened like Hippocampus kuda by medicinal beliefs and by trawling because it does not live anchored on the bottom.

The newborns nourish of copepods and rotifers, but almost half of them dies among the sea anemones tentacles © Rick Stuart-Smith, Reef Life Survey

Moreover, it is not required by the aquarium fish trade, because besides the feeding difficulties and the necessity of big pools, it needs chilled water.

Only a few public aquaria have been able to exhibit, like jewels, some specimens of Phyllopteryx taeniolatus and to grow the kids carried by the males.

Since 2017, this species appears in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as “LC, Least Concern”.

It is however to be kept in mind that the environmental degradation linked with the human activities, with the reshuffling of the coasts and the incessant pollution caused by the fertilizers that accumulate in the sea, cannot go on without damages to the shallow waters where they live.

Synonyms

Syngnatus taeniolatus Lacepède, 1804; Syngnathus foliatus Shaw, 1804; Phyllopteryx foliates (Shaw, 1804).

→ For general information about FISH please click here.

→ For general information about BONY FISH please click here

→ For general information about CARTILAGINOUS FISH please click here.

→ To appreciate the BIODIVERSITY of BONY FISH please click here.

→ To appreciate the BIODIVERSITY of CARTILAGINOUS FISH please click here.