Family : Cercopithecidae

Text © Dr. Giulia Ciarcelluti member API

English translation by Mario Beltramini

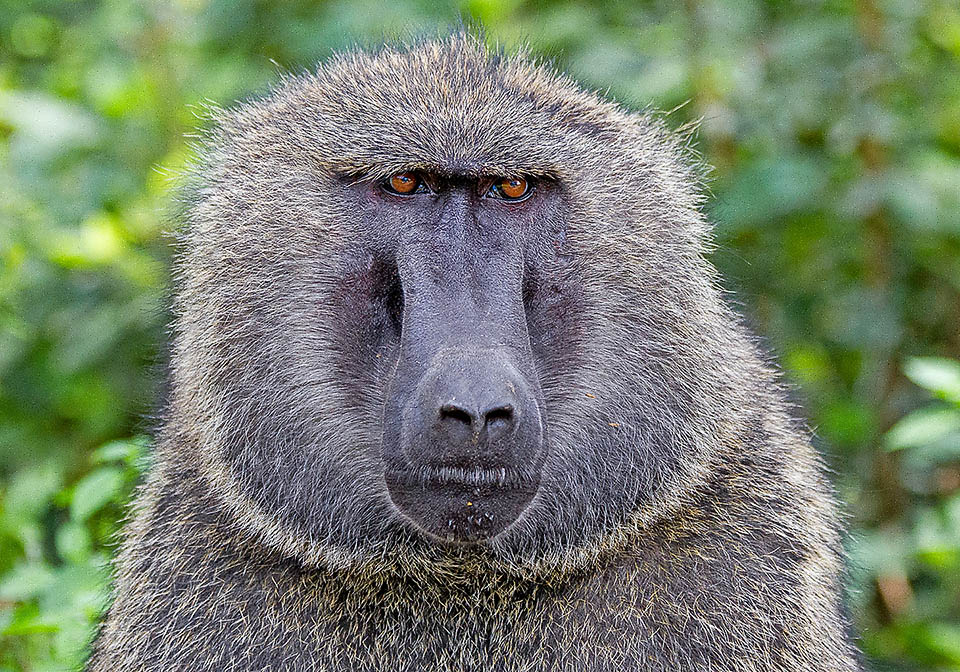

To the alpha male of Papio anubis is often sufficient a look to be obeyed, instantly, by all members of the group © Rob Sall

Papio anubis Lesson (1827) is a species of Monkeys of the Old World (Simiiformes Catarrhini) of the family Cercopithecidae.

The specific term anubis and the names under which the species is commonly known, Anubis baboon and Olive baboon, refer to Anubis, a deity of ancient Egypt, often represented with the head of a jackal or of a wolf, and to the coat that is olive in colour.

The generic name, Papio, comes from the French “babouin”, which in turn is similar to the Italian “babbeo”.

If it yawns then all tremble: in fact it exceeds 80 cm and 25 kg of weight with impressive canines © Robert Muckley

As well as Baboons, the species of Papio are also called Paviani, a name perhaps coming from the Italian city of Pavia.

The Anubis baboon, standing among the largest baboons, has a robust body, with the males reaching the average length of more than 80 cm and a weight of about 25 kg, whilst the tail usually exceeds 50 cm.

The females are smaller than the males and averagely reach the length of 60 cm, weigh about 14 kg and have the tail usually measuring 48 cm.

The head of the Olive baboon is massive and, like in the Catarrhine Monkeys, has a flat nose, with close and more or less open nostrils and facing forward, unlike what is observed in the other baboons of the genus Papio.

The top of the head is flat, a characteristic that distinguishes the Olive baboon from the Yellow baboon (Papio cynocephalus Linnaeus, 1766).

The face has close-set eyes and is glabrous.

The long and pointed snout is dog-like, with dark grey skin tending to black, in both sexes.

The mouth of Papio anubis is armed with robust teeth that, in the adult males, are more developed and form mighty weapons.

Furthermore, the mouth is equipped with two large cheek pouches that, while looking for food, allow to store the food already collected.

The fatty calluses of the buttocks are large, hairless and of bright red colour.

The Olive baboon, like the other congeneric species, displays a marked sexual dimorphism, with the males who, unlike the females, distinguish for the presence of a sort of big mane in the anterior part of the body.

And moreover, the males present the skull with thick bony crests on both sides of the nose and a prominent bone rounded above the eye sockets.

It’s twice as large as females and also the rebellious young males must obey immediately if they don’t want to taste its bites © Michael Heyns

Furthermore, as already mentioned, the males weigh about double than the females and their canines are greatly developed.

Plantigrade animal, adapted to move on all fours on the ground, the Olive baboon presents the front and rear limbs, of practically the same length and with opposable but short thumb.

The tail is of medium length, is provided at the extremity with a tuft of hair and is never prehensile and is often kept folded with a strong downward angle, which makes it appear as if it were “broken”.

Unlike Papio cynocephalus, the head of Papio anubis is typically flat. The snout, long and pointed, is canine in shape with blackish skin © Giuseppe Mazza

Due to these morphological characteristics, as well as for the four-legged gait, this species is somewhat reminiscent of a dog.

Zoogeography

The distribution of the Olive baboon extends through most of central and sub-Saharan Africa. Isolated populations are found also on the mountainous areas of the Sahara region.

Ecology-Habitat

The groups of the Anubis, present in tropical and Saharan Africa, usually spend the night on the trees or rocky cliffs to escape predators © Luis G. Restrepo

Papio anubis, of which have been described various subspecies, is met in very varied environments, such as the savannah, evergreen tropical forests, semi-desert zones, steppes, mountain forests, semi-arid woods and even areas close to urban settlements.

It has diurnal habits and dedicates most of the day looking for food.

The night hours are dedicated to rest by taking refuge on rocky cliffs or on trees in order to escape from possible predators.

They come down to feed and their erect position allows them to observe the territory © Arnaud Delberghe

The Olive baboon is mainly a terrestrial four-footed animal, but succeeds, when necessary, to move on two legs albeit for short periods of time.

It is able to climb trees to scan for any possible danger or to get a specific food.

The Olive baboon is an opportunistic omnivore, a thing which allows him to colonize different environments.

The ability to adapt to a low-quality diet based only on vegetables allows this monkey to survive for long periods of time in conditions of food scarcity and to adapt to inhospitable habitats.

The vegetable part is quite varied and includes grasses, roots, tubers, leaves, exudates, cactuses, mushrooms, as well as fruits, flowers, buds, seeds and bark.

The populations living close to the forests eat mainly fruits, whilst those close to the savannah feed chiefly on seeds and grasses.

During the dry season, the Olive baboons dig into the ground to get roots, tubers and corms in order to integrate the scarcity of food.

The diet of the Olive baboon also includes insects, scorpions, spiders, birds and eggs.

Both males and females are skilled hunters that, with various hunting strategies, manage to kill small birds, rabbits, foxes, lizards and even other primates and gazelles.

The proximity of human settlements to the Olive baboons’ habitat allows these primates to raid cultivations of corn, bananas, sugarcanes and beans.

On an ecological level the Olive baboons play an important rôle in the aeration of the ground by means of the excavation of corms, roots and tubers, and are dispersers of the seeds of fruits and cereals they eat.

Natural predators of the Olive baboon are: the hyena, the crocodile, the leopard and the chimpanzee.

Ethology-Reproductive Biology

Social animal, the Olive baboon lives in mixed communities of males and females, of about 15-150 individuals.

Besides leaves and fruits fallen down, Papio anubis finds always something to eat: insects, scorpions, spiders, birds and eggs © Rosemary Locock

Each community is hierarchically organized.

The reproductive behaviour of Papio anubis is promiscuous and strongly related with the social organization of the species: living in mixed communities, there is the possibility for each male to mate with any female, a thing that creates great competition among the males.

Normally, the correlation between the hierarchical position of the male within the group and its reproductive success is valid.

Roots, tubers, leaves, exudates, cacti, mushrooms, flowers, buds, seeds, bark allow them to survive under any circumstance, and here the infant has already ogled the fruits © Roger Wasley

Other social dynamics concurring to the reproductive success of a male are the alliances with other males within the group that can subvert the established hierarchy.

The males also follow a development strategy of “friendship” with the females, that increases their mating opportunities. In these friendships, teh males dedicate themselves to grooming (cleaning of the hair), share the food and have strong affiliative links with particular females and their progeny.

It’s no coincidence that the colour is inviting, and look tasty © Achim Mittler

It is common for the males to defend their own friends during competitive meetings with other females and with other males.

These relations are not limited to the period when the females are sexually receptive, but persist throughout the female’s life.

The females tend to display a preference for mating with their male friends, and therefore render more probable a faithful relation with their male friends.

Moreover, as the females of Papio anubis prefer their friends as partners, it is most probable that they cooperate with them in maintaining a relationship. rather than cooperate with other less favoured males.

In the females, the rank is inherited from mother to daughter, because these remain in the family group and the leadership determines the accessibility to food and the opportunities to reproduce.

Within every community, the matrilineal lines have their own hierarchies.

The females maintain and strengthen their social bonds with the grooming, and stay close to the females of their own family during the times of rest.

The males leave their birth groups at the time of maturity, when about 6-9 years old.

During the rest of their life, they move from one community to another every few years, to avoid hybridization with their own progeny.

When they approach a new community the strategy of the males is to appear friendly, creating links first with the females and the solitary males who do not enter the hierarchic line. Later on, they try to enter the hierarchy and to climb it, comparing themselves with the male holders of the leadership, in aggressive and highly competitive clashes.

At the same time, when there are no resources for which to compete (food, reproduction), the males respect the existing hierarchy and keep tolerant of each other.

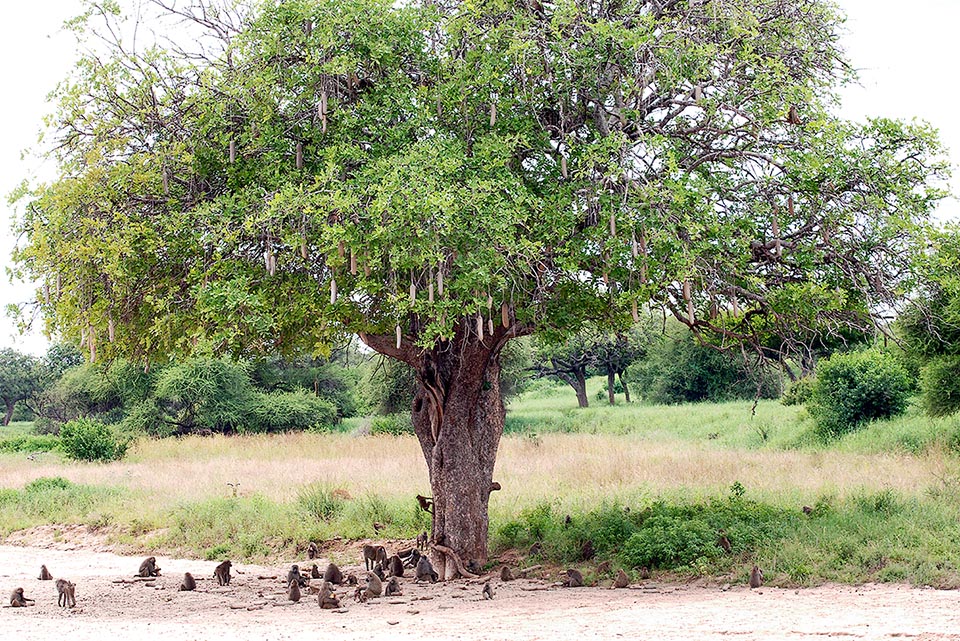

After such a long walk here the group rests in the shade of a majestic Sausage tree (Kigelia africana) © Harvey Barrison

Many are on the ground and with a little bit of ingenuity can be munched © Harvey Barrison

When they have conquered good rank in the hierarchy, the adult males are used to form coalitions among themselves, often for protecting the females in estrus from the young turbulent males.

An interesting phenomenon in Papio anubis is the secondary transfer of old adult males from their groups.

As the ability of a male to compete for mates is linked to the youth and the vigour, or with the long term social relations with the females, the transfer in a new group in old age reduces the opportunities of a male to mate.

The leader surveys and ponders. There are so many females. But one day it will get old and it pays to build alliances © Rob Sall

Furthermore, the transfer in a new group exposes a male to a large number of dangers, among which an increase of the risk of predation and dangers deriving from the aggressivity during the integration into the hierarchy of male dominance for the group.

On the other hand, should they remain, it seems that the old males that once had high dominance degrees are subject to constant harassment from the younger males, who appear to remember the old “grandeur” of such older males.

It seems however that the males with a greater number of female “friends” have more probability to remain in their group despite the harassment.

The sexual maturity is reached at the age of 4-6 years, whilst the actual adulthood is around the 7-10 years.

The females typically have an estrous cycle of 31-35 days.

There is a remarkable menstrual flow lasting 3 days, by any cycle, if the female does not conceive.

In the period close to the ovulation, the genital area of the female swells, becomes of pink colour and aliphatic acids are produced, tha work as chemical sign for the males of its potentially fertile condition and increase its attractivity.

Mating may occur during the whole year, and the males as well as the females can have multiple partners.

When oestrus is present, male and female court, mate, groom each other’s fur and spend enough time together.

In Papio anubis, the females are usually receptive during 15-20 days per cycle and in this period of time they mate with more than one partner: these multiple matings can confuse the actual paternity of the progeny of the female, which helps in mitigating the infanticidal tendencies of the males.

The gestation lasts 180-185 days.

The infants depend totally on their mother until weaning, around the 10-12 months.

After weaning, also the males begin to take care of the little ones in order to allow the females to look for food and dedicate to the cleaning of the fur: this is a fundamental phase where the infants observe the social dynamics of the group, teaching they will carry with them when they leave their group of origin.

In addition to hard ways also the male and female friendships matter, and grooming some subject is a passport for the future © Rosemary Locock

The females have an interval between births from 12 to 34 months. This interval varies depending on a series of factors: the oldest females or of higher rank tende to have shorter internatal intervals.

Most of the parental care is borne by the mother. The females breastfeed, clean and play with their offspring. There doesn’t seem to be a cooperative care of the offspring among the females in Papio anubis, but it is not rare that the females other than the mother take care of an infant. The subadult and young females, who have not yet reproduced, display with greater probability an alloparental behaviour.

Mother with infant. Also females form alliances to defend from unwanted males and to survey the progeny © Giuseppe Mazza

As is the case of all baboons, the infants are very attractive to the other members of the social group and they stand at the centre a great deal of attention, especially when still presenting their black hair.

The males have complex relationships with the newborns and the young, that in some cases may be a form of parental care.

They are known for transporting, protecting, sharing the food (especially the meat), cleaning and playing with the progeny of their friends.

As it is more likely that they mate with their female friends than with other females, these newborns and young are more likely to be their offspring than to other immature animals within the group.

The relationship between adult males and the immature can be even more complex: the adult males often bear stuck to their ventral zone the kids during agonistic interactions with other adult males.

This contact can have the effect of inhibiting the aggressivity on the part of other males, thus having the effect that the newborn acts essentially as a “shield”.

Communication

The communication in the Olive baboon is varied and complex and includes vocalizations, facial expressions and gestures.

In the visual communication stands the “social presenting”, the display of the anogenital zone, and it is used by the females towards the males.

The same behaviour can be also a mark of submission, when accompanied by the smacking of the lips.

The chattering of the teeth and the smacking of the lips, though not even being vocalizations, are auditory signals of reassurance, often done by a dominant male when another individual appears.

When danger is imminent, the Olive baboons give out a cry of alarm, a series of high-pitched barks, to encourage the others to flee that area.

Infant already grown up. Seems to wrinkle the face but life is nice © Bruno Conjeaud

The grunt is the most common vocalization used in all ages and in many social situations. The vocalizations emitted by Papio anubis include a “barking”, or call “wahoo”, that the adult males address to the feline predators or to other males.

Yawning, staring, raising eyebrows and grinding the teeth are warnings and signals of aggressivity.

The adult males emit vocalizations that seem grunts as menace and a vocalization that recalls a “roar” during the fights.

A strident roar that is a deep and resonant call, is emitted by the alpha male after a fight, and at times is emitted by the adult males when a nocturnal threat is present.

Shaking heads, clapping jaws, flattening ears and even sticking out the tongue are some of the communication facial expressions.

The clicking of the tongue is a versatile display that can transmit pacification reassurance and submission. It is often used while grooming and during the mating contexts.

Tail extension, fearful grins and the rigid crouching are all submissive behaviours.

In the baboons tactile communication is common. The social toileting (grooming) is utilized for strengthening social bonds, as well as for removing the parasites and the dirt from the fur. Social mounting is a behaviour used to reassure.

Conservation

Papio anubis is not a species of primate at risk of extinction. However, the conflict with human beings, especially farmers, breeders and hunters, renders this species worthy of special attention.

In some areas of Nigeria, the Olive baboons are hunted for their flesh.

High risks are associated with the consumption of their flesh as they are carriers of the Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), the Ebola virus and of a bacterium closely related to syphilis.

It can already climb trees, play with friends and follow the mother in an upright position. Perhaps one day he will be the boss © Joel Greenblatt

The growth of the human population, the loss of habitat and the transmission of diseases have the potential to threaten the survival and to have a significantly negative impact on the conservation status of Papio anubis.

The Olive baboon is listed in the Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), an international treaty among governments whose aim is to ensure that the international trade in animals and wild plants does not threaten their survival.

Papio anubis appears as “LC, Least Concern”, in the IUCN Red List of the endangered species.

→ For general notions about Primates please click here.

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within the PRIMATES please click here.