Family : Hominidae

Text © Dr. Silvia Foti

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Alpha male of Pan paniscus. It’s the anthropomorphous monkey closest to man © Giuseppe Mazza

The Bonobo (Pan paniscus Schwarz 1929) is a primate belonging to the group of the so-called “anthropomorphous apes”: it is a member, in fact, of the Superfamily Hominoidea and, in the context of this, of the Family Hominidae.

The bonobo shares the genus where is classified, that is the genus Pan, with its much more famous cousin, Pan troglodytes, the chimpanzee.

For a long time it was thought that these two primates did belong to a unique species: the bonobo has been recognized as separate species only in 1933 and later genetic studies have fully confirmed the present taxonomical classification.

The two “cousins” would be separated, in fact, by a difference in the genetic heritage equal to the 1% of their sequences and such evolutionary separation is deemed having occurred starting from about 1,8 million of years ago.

The reason of such separation appears to be attributable to the presence of the Congo River in the geographic area where the two species do live: the bonobo and the chimpanzee, distributed on the two opposite bans of the river, should have met a process of allopathic speciation not been provided, unlike the man, of the ability of swimming and, therefore, to come into contact.

Undoubtedly fascinating is also the remarkable resemblance between the bonobo DNA and the man’s one: like for the chimpanzee, also for the bonobo the level of closeness to mankind, on the genetic point of view, renders it as one of its closest “relatives”, so much that in the past some scholars had suggested to move the man into the genus Pan or, alternatively, to reclassify the bonobo, as well as the chimpanzee, into the genus Homo, with one of the following names: Homo paniscus, Homo arboreus or Homo sylvestris.

The bonobo is a species already suitable for bipedal stride. The female, 10 cm lower than the male, weighs 20 kg less. The chest, only case for apes, is prominent like humans © Giuseppe Mazza

At the state of the current knowledges, we know that the genetic differences between man and bonobo are not really negligible, as they might approach the 6% of the genetic heritage.

A really amazing news, however, talking about resemblances between man and primates, is that, though since always we think to the chimpanzee as the most similar monkey to the man, for some scholars it should actually be the bonobo to hold physical characteristics more similar to those of the man’s ancestors.

Such statements would be based on the fact that the bonobos have a physical structure more suitable to the bipedal stride, that in fact they practice it more than the chimpanzees, but also comparing their body structure with the bone remains of some australopiths.

Nevertheless, this hypothesis is not fully shared by the whole scientific world.

For what their common name, bonobo, is concerned, this has not a scientific meaning: it seems that it comes from a lapsus calami, bonobo instead of Bolobo, a location present in the former Zaire, the present Democratic Republic of the Congo, on a crate containing a specimen of Pan paniscus rightly addressed to Bolobo.

Zoogeography

The bonobo lives in the geographic area south to the Congo River, whilst the north area is occupied by the chimpanzee.

Ecology-Habitat

Bonobos habitat is mainly formed by the tropical rain forests of the Congo Basin included in an area bordered by the Congo River and the Lalaba, and by the area north to Kasai River, but it characterizes due to the presence of a high degree of heterogeneity due to the presence of areas converted to cultivations and others reverted to forest, and therefore “young”, factor rendering the typology, the density and the height of the trees extremely variable.

The males often display their exuberant virility © Giuseppe Mazza

It seems that the bonobos use all these typologies of habitat, preferring, however, an altitude included beaten the 300 and the 700 meters.

Whilst the research for food takes place in any type of habitat, the night resting hours are mainly spent in the woody zones, where the bonobos use to build nests on the trees, at heights varying from 5 to 10 metres from the soil.

Pan paniscus mainly nourishes of fruits, but it includes in its daily diet also other parts of the plants, from the seeds to the leaves, from the buds to the roots, even to the tubers, to the flowers and to the medulla, for a total of more than 150 vegetal species consumed.

Also the fungi, the honey and small invertebrates, though in lesser quantity, are part of the diet of the bonobos.

It has been observed, moreover, also a sporadic consumption of meat: unlike the chimpanzee, it does not go hunting actively but, if occasion arises, it kills small mammals such as Flying squirrels (Anomalurus sp.), Bay duikers (Cephalophus dorsalis) and Black-fronted duikers (Cephalophus nigrifrons) and dedicates to fishing, entering the water and catching the fishes.

Overall, from the aliments of vegetal origin the bonobos get the most of the nutrients intake, proteins included, and only the remaining protein requirement is satisfied by the proteins of animal origin.

It’s rare that the passing by females do remain indifferent © Giuseppe Mazza

A curious thing concerns the use of instruments for getting the food: contrary to the chimpanzee, exclusively user of tools, the bonobos in the wild have been seen using instruments in a sporadic way and mainly for making a headgear with the leaves, in order to shelter from the rain, or a toothpick, from a sprig.

Finally, they have been observed using mosses like sponges, soaking them in pools of water for quenching their thirst.

Another difference in respect to the chimpanzees is also their tendency to move among the trees to cover short distances or to escape possible dangers: if necessary, in fact, the bonobos demonstrate excellent brachiators, swinging from branch to branch, or opt for short jumps using all four limbs.

Morpho-physiology

The bonobo is often defined the “pygmy chimpanzee”, despite its size is not particularly small, much less if compared to those of the Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes).

It is thought, therefore, that the term “pygmy” probably refers to the geographic area where these primates do live, that coincides with that inhabited by the human populations of the Pygmies.

The females show their reproductive oestrus status with the swelling of the perianal tissues © Giuseppe Mazza

Their sizes almost reach the 2/3 of those of a human being, but the body is much more slender and streamlined than that of the chimpanzees.

With respect to these ones, in fact, they have thinner shoulders and neck, more rounded head with less pronounced cranial structures, more dilated nostrils, less prominent eyebrows, smaller head and ears, these last covered by the down of the muzzle.

The body is covered by a thick dark down covering also most of the face, contrary to Pan troglodytes, where the cheeks are mostly glabrous.

Moreover, we have to emphasize that also the parts of the body having no hair, that is the hands, feet and part of the face, have anyway a dark colouration, other peculiarity differentiating them substantially from the chimpanzees.

Their gait is mainly semi-bipedal, as they advance leaning on the knuckles; however, at times they can proceed with a fully bipedal gait.

In the specific, when they move for long distances usually they walk with semi-bipedal gait, whilst when they carry some food they may advance with three limbs leaning on the soils and the fourth used for holding the food, or completely bipedal.

However, being much more arboricolous than the chimpanzees, they can advance even for more than 1 km moving exclusively among the branches.

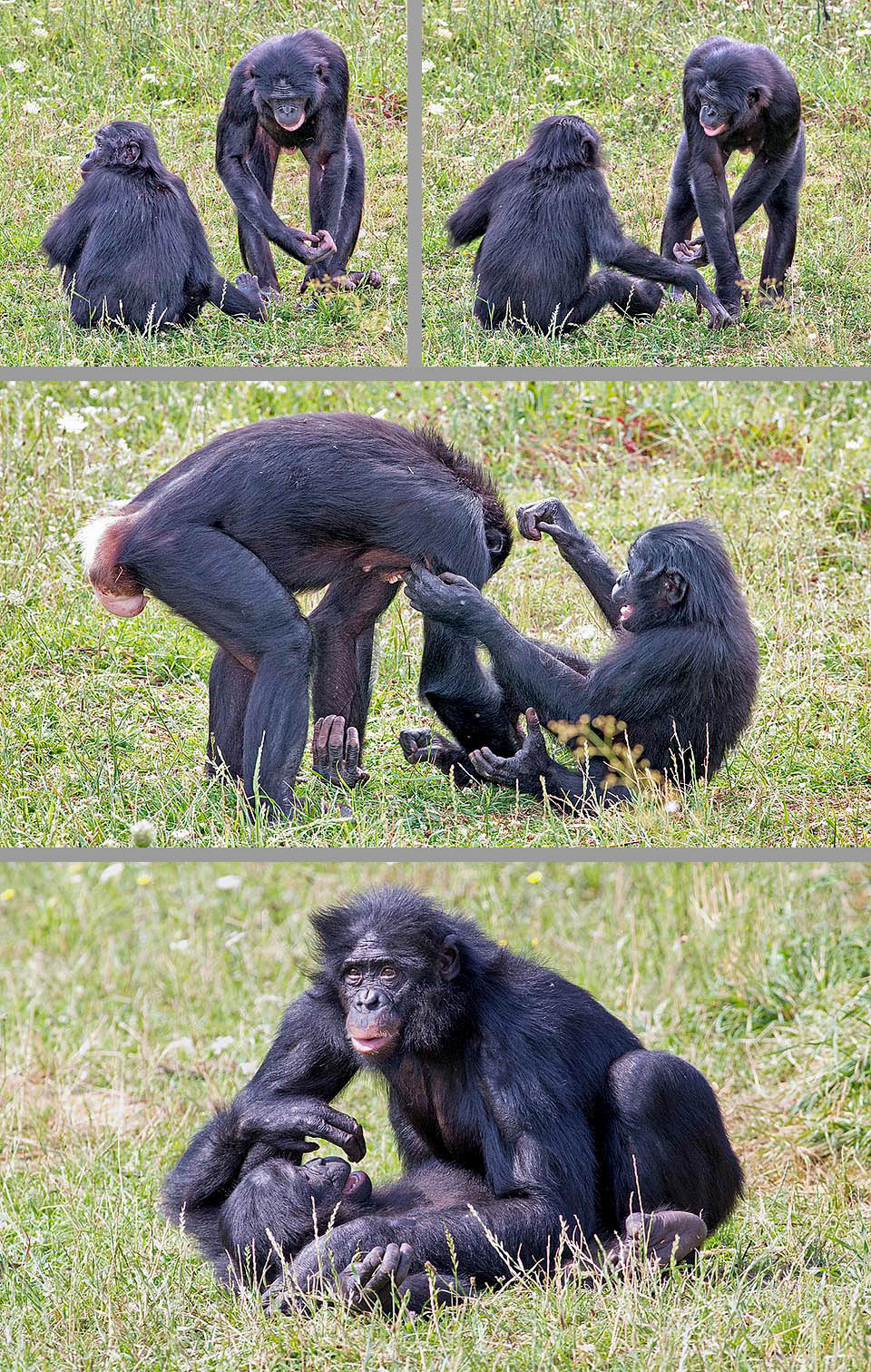

Make love not war. All hassles are smoothed with sex. Here two females quarrel and then rub their genitals in the liberatory ritual of a false copula © Giuseppe Mazza

Rightly thanks to this, the bonobo reveals also an excellent climber, taking advantage of the trunks of the trees.

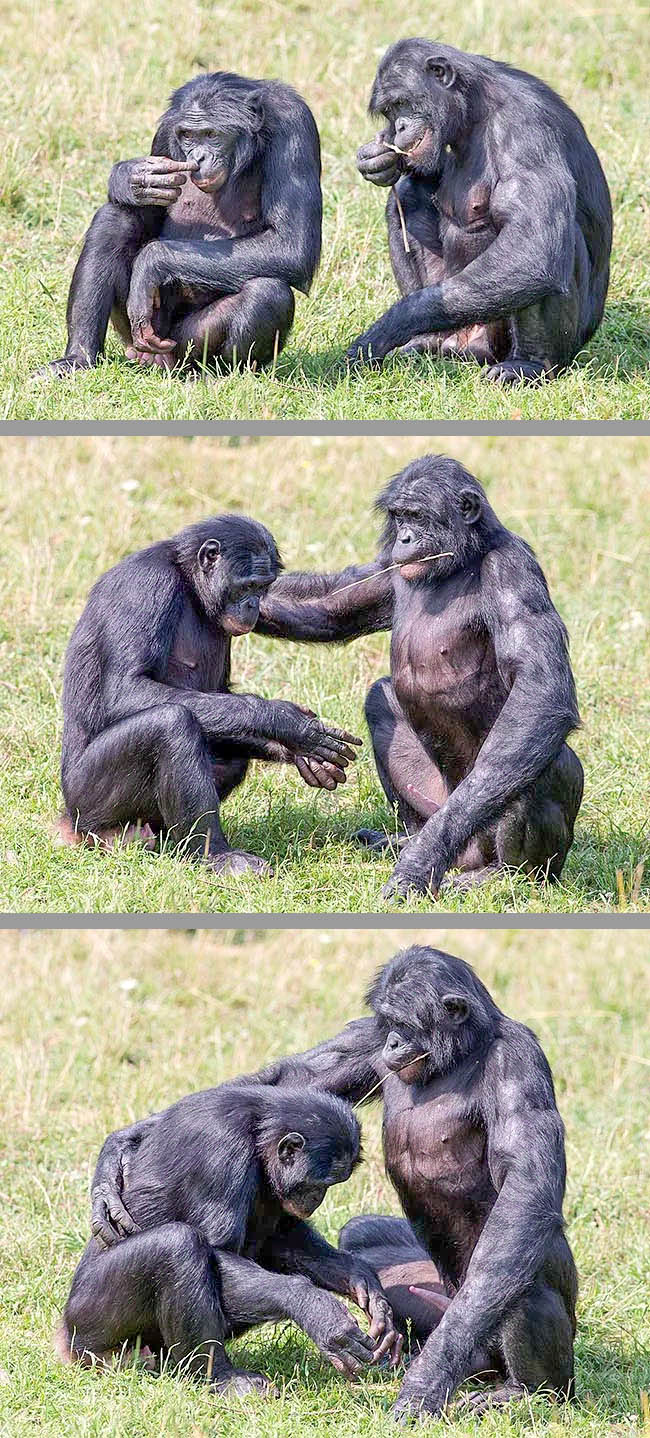

A pensive and dubious novice? The alpha, with the due sprig in mouth, encourages her showing its credentials © Giuseppe Mazza

When the bonobo is standing erect, thing happening much more frequently than the other primates, the arms reach below the knees.

The hands have long and tapered fingers.

The sexual dimorphism is little evident: the males have greater weight and height (as an average, 45 kg per 120 cm), in respect to the females (as an average, 33,2 kg pr 110 cm), even if the skeletal structure appears practically the same.

One of the few differences that can be found between males and females and that reminds on of the peculiarities of the human sexual dimorphism, consists in the greater development of the chest of the females, that appears more prominent if compared to the male one.

Conversely, the males have very developed canines.

Etology-Reproductive Biology

If from a physical point of view the differences between chimpanzee and bonobo are finally so much marked, from the behavioural point of view we can affirm without any doubt that the two species “cousin” represent “cultural” realities decidedly opposed: the bonobos are peaceful, relaxed, Dionysiac and easygoing and much prefer the cooperation inside the group, whilst the chimpanzees, in their comparison, appear as rowdy brawlers, where the conflictuality within the group is often the host.

Let us see then a little more in detail how the much more playful bonobos live.

They are polyandric; the females may usually mate with numerous males belonging to the same group, but with their own sons.

There is however an initial consideration to be done, useful for better understanding their reproductive system, as well as their sociality: the bonobos do fully represent the motto “Make love, not war”.

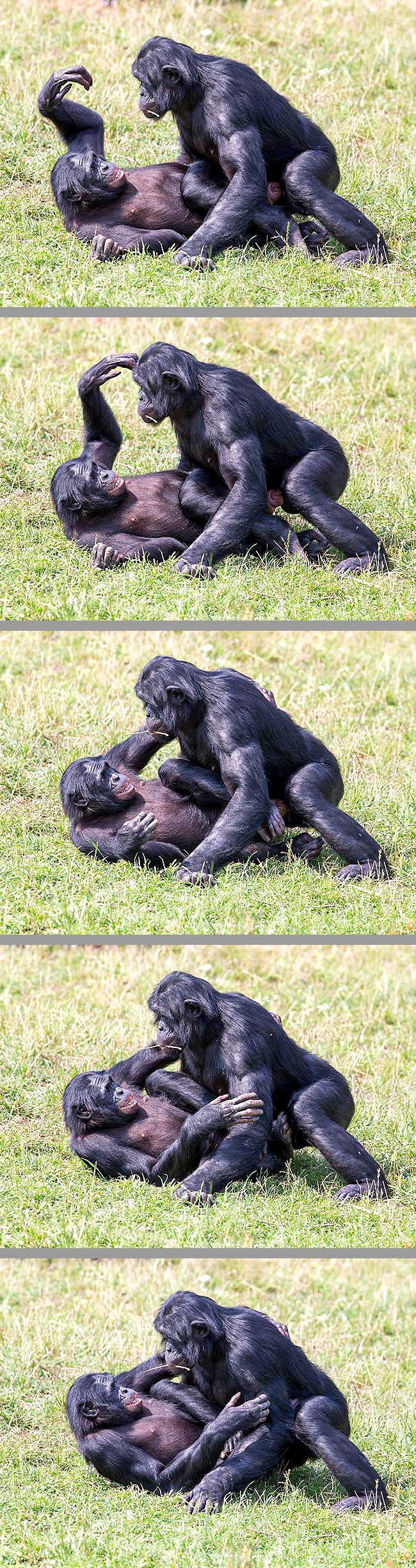

The sexual activity, for the bonobos, stands at the base of the structure of the society, as it is used to form and to mainatin the social links inside the group.

And rightly their own particular sexual liveliness should be at the base of the feelings of kindness, sensitivity, altruism, empathy and compassion shown and that render their societies splendid examples, in all the animal kingdom, of peaceful of peaceful coexistence.

However, the only limit that presently is met while describing in detail the dynamics ruling the bonobos society stands in the scarce number of studies bound to investigate this aspect, especially if compared to those existing that concern the chimpanzee.

Mating starts traditionally © Giuseppe Mazza

As a matter of fact, the bonobos have started to be studied only by the Japanese expedition that, in the seventies, investigated for the first time their behavior in the habitat of Congo and, more on detail, near the observation site of Wamba.

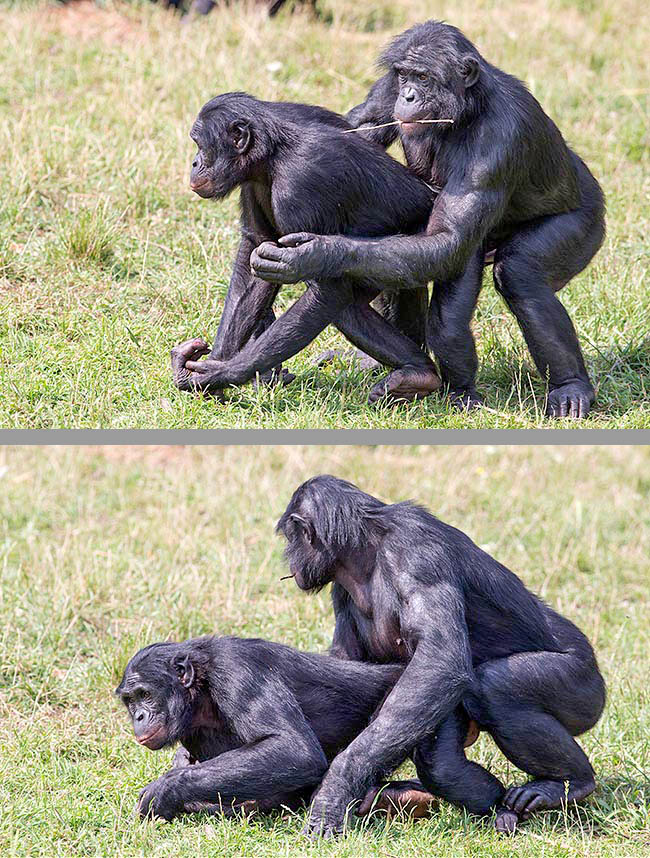

The females of Pan paniscus show their reproductive estrus status through the swelling of the perianal tissues, thing that represents the most evident sign of their period of maximum receptivity.

Usually, in fact, most of the matings takes place in the moment when the turgidity of the genital zone is at its peak, matings that may occur throughout the year.

For what concerns the period of post-partum amenorrhea, on the contrary, it lasts in some cases even less than one year.

After this time, in fact, in most of the females we see again the characteristic perianal swelling to which, actually, does not correspond a real reproductive fertility, probably also due to the breastfeeding.

The females can breastfeed the progeny even up to the 4th year of age.

However, though it is thought that the lactation can really inhibit the female fertility, because nowadays there are no precise studies bound to determine how many sons can generate a female during all her life.

During the oestrus period, the swelling of the genitals is a clear recall signal for the males, who approach the females exhibiting their genitals erect; on their side, the females do not refuse a coupling, showing no indifference at all in front of the male’s spectacular display.

Then the female turns and so can smile to the spouse and embrace him dearly. He is always deadpan with its sprig in mouth. The alphas control a group of even 10 units. Fidelity and jealousy don’t exist © Giuseppe Mazza

Nevertheless, it is quite a very difficult thing to be able to establish who is the true father of a newborn: the bonobos, as we have said before, reveal being “broadminded” and the female during her reproductive period can mate with various males belonging to the group, apart the sons.

For what concerns the development of the progeny, the adult age is reached only by the 15 years, a long period of time during which the sons cultivate a strict relation with the mother: she is, in fact, the one furnishing most of the parental cares.

However, the males, maybe due to the unsure fatherhood, contribute indirectly to the growth of the kids: they alert the group, share the food and protect the young.

The weaning, that occurs by the 4 years of age, foresees the mother teaching the son how to get the food and what foods to prefer, rather than furnishing them directly.

Contrary to what happens in the hamadryas, in the bonobos the males remain inside the natal group when adult, so to continue in having contacts with their mothers, whilst it’s the females leaving it.

They are social animals and live in groups formed by males, females and young.

The typical dimensions of a group go from the 3 to the 6 individuals, but can reach even the 10.

It may happen, also, that more groups melt temporarily in sites where is a particular abundance of food, to then divide and resume again the initial dimensions.

Inside the group exists a hierarchy of male dominance: the degree of hierarchy of a male depends strongly on the social position of the mother, as, the more this will have prestige inside the group, the more the son will get ahead inside the group itself.

Moreover, the females build up solid alliances and create strong links with each other, thus to reduce the frequency of the aggressions against them by the male specimens.

The dominance is naturally reiterated and maintained, every time the alpha male thinks it is necessary, through menace signals towards the other members of the group, who, usually, retreat without giving rise to real confrontations.

Furthermore it has been noted that immediately after a menace they usually practice reassuring behaviours, in order to dissolve any persisting tension inside the group.

Just in that regard, it is very interesting to resume the subject concerning the “sexual” behaviours and clarify in which extent these ones do contribute in maintaining firm and cohesive the group: it is thought that they are used as a negotiating tool, but also for maintaining the social status, in both sexes.

The females as well as the males, in fact, may show some particular non copulatory attitudes that include contacts female-female (such as the GG rubbing – genital genital rubbing, that is the rubbing the genitals of one with those of the other), contacts male-male (mount and rubbing of the rump of one by the other) and juvenile behaviours, continued for long time, consisting in mimick of copulatory acts, without, however, a real penetration.

These attitudes are shown usually among all the members of a group, and become particularly frequent every time a new female leaves her natal group for joining a new one, in order to speed up the creation of strong social links with the new members.

In addition to this, the bonobos make extensive use also of the grooming: during the resting periods it is quite frequent thatb two females or a male and a female brush down the hair mutually, signal interpreted as a display of inter-individual affinity or of cohesion and harmony inside the group.

These displays of “affection” are not rare not even when bound to members of other groups: some studies done exclusively on the captive bonobos have evidenced the phenomenon of the “third party affiliation”, that is the affiliative contact, that can manifest in form of hugs, caresses and grooming offered to the victim of an aggression by a member of a group different from the aggressor’s one.

This behaviour seems to contribute to mitigate the stress of the victim of the aggression and to reduce the possibility of future aggressions against her.

The male deals with the group security, whilst the female for four years must breast feed and educate the son, showing him what to eat and how to behave © G. Mazza

Besides these modalities of communication, the bonobos emit numerous vocalizations: the females by means of screams, the males, on the contrary, through grunts, verses and whistles. The contexts in which these vocalizations are used are various: they express aggressiveness, satisfaction, excitement, but also a looming danger ot threat.

Bonobos don’t neglect the body care. They make full use of grooming, currying the hair as friendship sign also to other groups members © Giuseppe Mazza

Like the tactile and vocal communication, the bonobos utilize also the visual one: they can turn their gaze with particular attention to some individuals, especially if these ones handle some food particularly desired, or if they are females in oestrus, as courting sign.

Bonobos don’t neglect the body care. They make full use of grooming, currying the hair as friendship sign also to other groups members © Giuseppe Mazza

Being extremely playful, the bonobos have developped many behavioural patterns referable to real “games”, particularly since the playful aspects appears to be an important component also in social and sexual contexts: they are not only the young individuals who play, in fact, but also the adults and even adults and young may indulge in entertainment sessions together.

Generations meeting between males: a stately alpha and the kid, just bigger than his hand © Giuseppe Mazza

In the sexual relations, then, it seems that the play is a sort of a prelude to a passionate meeting, whilst inside the society it seems to serve for easing tensions and strengthening the link between the components. Obviously, before starting a moment of play, an individual shows its peaceful intentions to the other mate by means of a specific facial expression.

Yes, it’s just a willy, but one day I will also be an alpha … I have already learnt to keep the sprig in mouth! © Giuseppe Mazza

Unlike the chimpanzees, who prefer to play sith the young and soon lose the interest towards the game they are carrying on, the bonobos do not have particular preferences about the age of their playmates, but especially, like children, they adore to play for long time and try to keep high the level of interest of their mate, towards such activity.

Curiosities

– A really curious peculiarity is that the bonobos, like humans, may manifest baldness in old age.

– Presently the information related to the longevity of the bonobos are fairly limited as any research conducted on these primates has concerned the entire vital cycle of the specimens studied. We can infer the life expectancy of the bonobos, however, from the only semi-continuous study carried on in 1976 in the Wamba site: from the data collected it would appear that the bonobos may live more or less as long as the chimpanzees, that is up to 45-50 years.

– It is good to precise that, about the sexual practice of the bonobos, that these ones, actually, are not the only ones to utilize the matings as powerful social tool: also the baboons and other species of primates use the sexual behaviour for smoothing threads. However, the bonobos stand out for the huge variety of sexual practices, often quite imaginative, that highlight their great inclination to inventiveness and to the play.

– After the Red List of IUCN, the bonobos are a species “EN, Endangered” threatened with extinction and is expected a reduction of the 50% of their number, or even more, within three generations, due to the exploitation and the distruction of their habitat. Moreover, the bonobo is victim of the poaching done for getting meat and medicinals or for the pet trade.

– Rightly a bonobo, named Kanzi, has entered history as the first communicating ape, as, after some researchers it was able to articulate some understandable spoken words.

– Finally, a last point of thought about this good-natured, peaceful ape is offered us by Caparezza, singer certainly liked among youngsters. If what you have read is not enough, then listen to his Bonobo Power and you will appreciate it even more!

→ For general notions about Primates please click here.

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within the PRIMATES please click here.