Family : Phasianidae

Text © Dr. Gianfranco Colombo

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Other than battery animals! Not even a snowstorm is capable to stop this intrepid male of Wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) in South Dakota © Charles G. Summers, Jr.

The arrival of the Europeans in the North American soil has marked irremediably the destiny of the Wild turkey, placing it, without any euphemism, at the centre of attention of the newcomers, and also at the centre of the table of every diner.

These birds would have never imagined that one day, in order to follow a Christian tradition begun on the distant year 1623 by the Pilgrims Father who wanted to render thanks to the good Lord for the prosperity of that just ended vintage and for having survived to the difficulties of the life in that new land, they should become the sacrificial victims of every North American.

This female is surely not behind. The turkeys, native to North America, are not migratory birds and therefore have always known how to get by also during the bad season © Evan Jenkins

On the fourth Thursday of the month of November, all North American countries celebrate this day by consuming that baked Turkey accompanied by pumpkin, cranberry sauce or by corn pies, typical of the autumn season.

They say that are consumed about 50 million of them in only one day, although by tradition the President in charge, a few days before Thanksgiving Day, grants grace to a couple of specimens in the name of a hypocritical kindness enlivened shortly after, rightly, by a meal based on turkey meat.

By sure they are not eagles, but when needed, like this majestic male, also know how to fly © Charles G. Summers, Jr.

By sure, for the first Europeans who arrived in the American territory to settle there permanently, being now in a late season for sowing, after months of navigation and now at the limit of their strengths, it was easy to copy the customs of the American Indians, Algonquins, Massachusetts and Mohicans, nourishing of roots of pokeweed and of Jerusalem artichokes, of mollusks collected on the beaches and, naturally, integrating everything with those tasty and big birds, so common and easy to hunt with the modern weapons carried from the old continent.

So, that was the story of this bird from that moment crossed that of the humans, transforming from an initial vital necessity in a later and real food tradition. But the adventure of the Wild turkey had much larger and more profitable developments during the following centuries.

Three parading males. Colors don’t miss and they strut, as indicates the scientific name of gallopavo, that is Peacock rooster © Mark Heatherington

Its prolificacy and its ability to adapt also to a life in cage, added to the ease of hybridization and adaptability to undergo evolutionary changes, have led during the centuries to become one of the most versatile producers of meat, with specimens that at times display morphologies well different from the original ones.

It has covered the same way as the Gallus gallus who, from wild cockerel of the South-East Asian forests, has transformed in more than 70 varieties of chickens and hens of all colours and all dimensions, reaching a record seeing it as the most numerous bird of the planet with more than 30 billion of individuals.

Turkeys are social animals moving in group, led by a pack leader, usually an old male, and cover even several kilometres per day © David Jahn

The arrival of the Wild turkey in other continents has been the object of a nice misunderstanding that has misrepresented its beyond the Atlantic origin, thus in favour of folk names with a completely different origin.

In Great Britain, rightly the homeland of the Pilgrims Father, it was called Turkey, in France, Dinde = of India, as well as in the northern part of Italy, where it is often called Dindio, in Holland and in the Scandinavian Peninsula, it is called Kalkoen, Kalkon, Kalkun, Kalkkuna = “Chicken of Calicut”= Indian city, in Portugal is strangely called Peru, in the Arabic Middle East, “Chicken of Ethiopia” whilst easternmost, Arabs do call it “Roman chicken”.

Males head is carunculate, greyish when resting, but fiery red and even azure when the animal is excited, as in this case. On the crop, on the chest and from the nose dandle no less flaming characteristic wattles © Dave Lawrence

In Greece the Wild turkey is called French chicken, in Russian Indjuk area = Indian chicken as well as in Turkey, Hindi chicken and in Malaysia even Dutch chicken, such a geographical confusion is leaving astonished.

Japanese, for their part, have invented an even more amusing name, calling it Shichimenchou, = bird with seven faces.

The same confusion has arisen about the “Helmeted guineafowl” (Numida meleagris) by the British and many European countries that had called it Guinea fowl = fowl of Guinea or Pintade de Numidie in French or Gallina de Guinea in Spanish, whilst for Italians it was a more high-ranking Faraona d’Egitto.

The origin of the misunderstanding has come from the fact that at that time the merchants of poultry passed off as good, in absolute good faith, the provenance of any strange bird from the most unlikely countries and the Turkish dealers were masters in this at that time, hence this is the origin of the Anglo-Saxon name, whilst in their own country, fantasizing even more, they did call it Indian chicken.

Even on the coasts of the Balkans they called it also “chicken coming from the sea”, just because from that side they saw the dealers of the time coming but also in eastern Africa, with Giant hen, they have been able to satisfy their fantasy.

Other international common names are Truthuhn in German, Pavo comun in Spanish, Dinde or Dindon sauvage in French.

The Wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo Linnaeus, 1758) belongs to the order of the Galliformes and to the family of the Phasianidae and is one of the biggest members of this family.

The scientific binomen gets its origin from the Greek ‘meleagris’ = Guinea fowl and from the Latin ‘gallopavo’ from ‘gallus’= cock and ‘pavo’ = peafowl.

For the sake of truth, Meleagris, in the old Greek mythology, was a great fighter, upon whose death the sisters were so sad the Artemis, out of pity, turned them into a bird whose feathers were stained by the white of their tears, rightly the Guinea fowl.

The vulgar names given locally in Italy are quite many and some more sound more like cute nicknames, even if most of them take up the above-mentioned themes: Pirillo and Pit, Bibbin and Pulin, Pita and Viccia, Nia and Billo, Lucio and Pao.

Female turkeys, without large wattles and frills on the chest, have paler colours and do not strut as males usually do © Bill Amidon

Zoogeography

Meleagris gallopavo is native to North America where it occupies the central-eastern belt of the USA, from the Gulf of Mexico to the southern regions of Canada and from Texas up to Oregon.

It is also present in the mountain part of Mexico and in some areas in California, in this last area it was probably introduced during the last centuries.

Introductions have occurred everywhere with some positive results in Germany.

Conversely, the farmed turkey is present in a widespread way and in big numbers in all continents.

It is impossible to determine the exact number of the specimens present in the nurseries of the whole world but presumably are constantly present in some billions of them.

The Wild turkey is a sedentary species and the number of the populations present is almost stable after the reintroduction during the last century, in the locations where it was scarce due to the strong hunting impact.

Still now, it is a species strongly hunted but it is kept under strict control by the naturalistic authorities to protect its survival.

Ecology-Habitat

Meleagris gallopavo is a terrestrial species and like most of the phasianids it spends the whole day on the ground in the open and semi-shady thickets where it scratches wandering looking for food in big family groups and covering and covering several kilometres per day.

The guide is led by a dominant male, usually an old one, who is in charge of defending the group, at times even sacrificing itself for saving the membres of its tribe.

Although the withered bush is their natural habitat, it does not disdain areas of open plain without trees but with low bushes, where, if needed, to hide from the predators and also in the swamps and in the mountain forests.

Male in full courtship. The sexual dimorphism is evident. It can reach the length of 120 cm and a weight of 11 kg, whilst the female is much smaller © Mark Heatherington

Conversely, during the night it becomes arboricolous, and perches on the high branches of leafy trees to avoid the many terrestrial predators present in their territories.

Meleagris gallopavo is not a great flier, on the contrary, the effort to keep flying is so big that it is most often avoided, but it is an exceptional runner that can move at more than 40 km/h, escaping most of the predators. Only in case of extreme necessity it takes off with a very rapid and violent beat of the short wings and with the typical and thunderous noise.

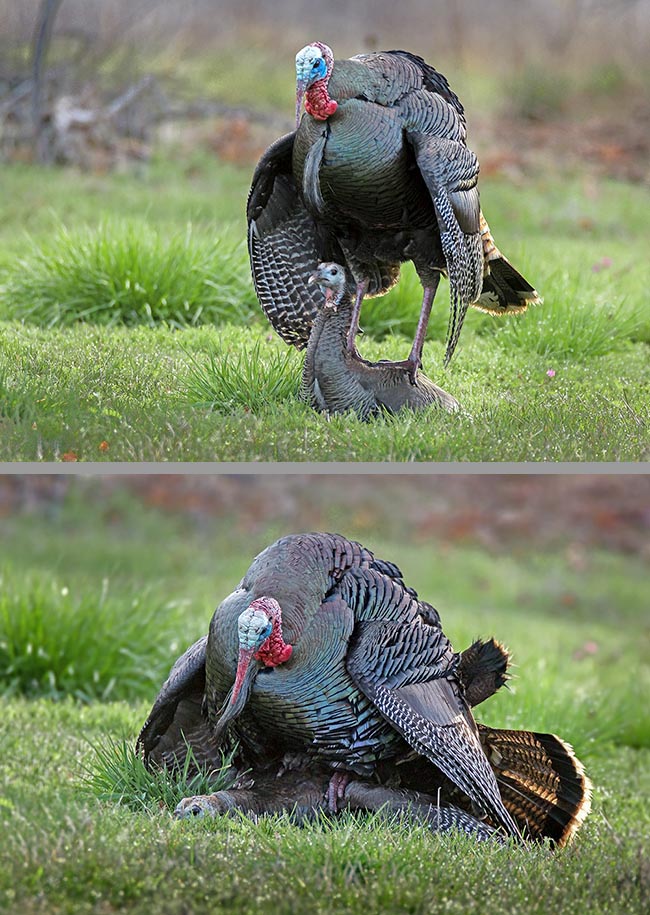

For mating it jumps on her back, whilst the partner on duty, under the strong weight, reflects flattened on the soil © Mark Heatherington

A flock taking off can terrorize even the most experienced intruder, with such a violent and sudden noise, to leave astonished for some seconds whoever is attending the event.

After that, covered a few tens of metres most of them gliding with curved wings, here it lands with a wild rush to cushion the descent and huddle behind some bush waiting for the danger to pass.

Morphophysiology

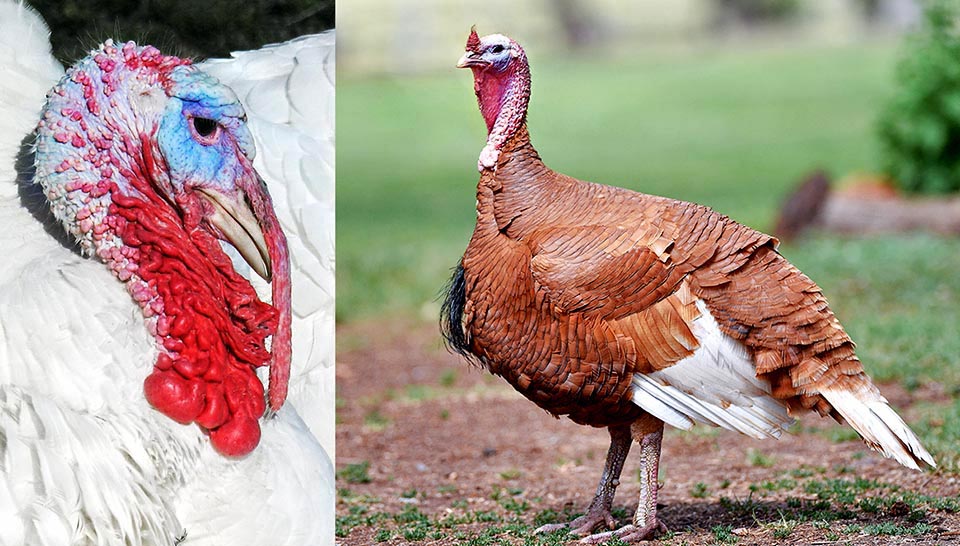

It is a must now to make two neat distinctions between the Wild turkey and the farming one.

The first one is now rather different from the second, in the morphology as well as in the livery and even more in the dimensions.

The wild one is about 12 cm long, with a weight of 4 to 11 kg, in any case linked to the availability of food and to the seasonality and with a wingspan of about 120 cm.

Completely different is the farmed species that sees specimens reaching even the 40 kg and of such dimensions to compete and contrast even the attack of a dog.

We cannot talk of the flying capacities of these animals now so sore and burdened by an extraordinary weight that would render any attempt to fly in vain.

The male of Meleagris gallopavo has significantly larger dimensions than the female and even well marked sexual dimorphism in the livery and in the behaviour.

Similarly, it might be compared to a Peacock (Pavo cristatus) with a bit modest livery but with the same social behaviours.

The male has big dangling wattles on the nose that grow from year to year until they form an accentuated growth, so much to cover part of the face and of the beak. An even more swollen outgrowth when it is excited during the courting of the defense of its harem.

The Wild turkey often attacks also the human being chasing him and pecking him vigorously as soon as it gets closer to its territory, be this a chicken coop, an open meadow or a small space of a farm.

Moreover, it is equipped with strong legs having heavily clawed fingers and a some centimeters long spur that it uses impartially to show the intruders the right way of escape.

Wild turkey’s nest is a dimple on the ground, covered by dry leaves and grass, often hidden sheltered in a bush. It contains 10-20 eggs, hatched by the female for 28 days © Alan Cressler

Also the beak is strong and slightly hooked and is suitable for looking in the humus and the leaves fallen on the soil as well as for seizing and dismembering alive preys it often hunts.

The traditional livery of the male turkey is well known to all. A blackish plumage with whitish edging of all feathers of the body, enough to make it look grizzled and with tail also black clear bordered on the apices it opens like a fan while courting. Its tail is formed by eighteen rectrices that have a rather stiff rachis that keeps them well stretched during the parade.

A just born chick, already gritty looking © Becky Matsubara

The head is naked and carunculate of greyish colour when resting but that turns fiery red and even azure when strongly excited. Also on the crop the wattles display round red ball swellings that hang on the chest dangling upon every movement.

Always on the chest, the male has bristly feathers going down like a gag creating an appendix similar to the purse that goes with the Scottish kilt or, even better, to the bristles of a broom carried dangling on the neck.

The females of Meleagris gallopavo have paler colours and have neither wattles nor frills on the chest and do not strut as usually males do.

The farm specimens usually have the same colours, even if the minor age allowed to them before being slaughtered, does not allow them to reach the brilliance of the shades of colours typical to the adult individuals.

Moreover, are usually farmed females having slightly paler colours as their flesh is much softer and juicier.

Then there are about forty domesticated breeds having quite different colours and hardly comparable to that of the holotype but very elegant and attractive. Among them, we cite the Ermellinato di Rovigo, the Black of Sologne, the White, the Sweden blue, the German red, the Bronzed of America, the Black winged bronzed, the Australian slate, the Slate and the Early brown.

In nature, only two species of turkeys do exist, both native to the New World, the aforementioned Wild turkey and the Ocellated turkey (Meleagris ocellata).

The latter is much more elegant in its livery that shows metallic golden shades and ocelli on the whole body and remarkably stronger colours. It can never be confused with the Wild as it lives confined in the Yucatan, as well as to show a completely different livery from that of the conspecific.

The hatch is almost simultaneous and in a few hours the brood leaves the nest, carefully followed during some weeks by the broody hen © Bruce Smith

The Wild turkey has six subspecies differing on the shades of the colours, the dimensions and the territories occupied. The Meleagris gallopavo silvestris, M.g. intermedia, M.g. mexicana, M.g. osceola, M.g. merriami and the M. g. gallopavo.

Ethology-Reproductive Biology

Meleagris gallopavo is an excellent reproducer and the female an unbelievable sitter guaranteeing exceptional results in the broods. Traditionally, in our countries, often the sitter is exploited for hatching the eggs of other poultry because it can guarantee good results and inevitable success.

Chicks are predated by coyotes, foxes, lynxes, raccoons, minks, snakes and raptors. Protected by a mimetic cloak, in two week they learn to fly for sheltering on the trees © Melanie Howarth

The female Wild turkey can remain on the nest incessantly for days, leaving rarely the nest, and for quite very few minutes, losing weight and strength up to weaken even considerably. The effort lasts about 28 days in absolute solitude as the female cares for the progeny since the conception.

Meleagris gallopavo is polygamous and mates with several females that it abandons immediately after, to lead an idle and disinterested life. The phases of the courting take place following a well known scheme that we often see repeated often in any place where these birds are raised.

In fact by night the wild turkey becomes arboricolous and perches on high branches of leafy trees to avoid at least the terrestrial predators © Roy DeLonga

Strutted tail, wings lowered to touch the ground vibrated frantically as if they were hit by hysterics, head back, reddened and swollen wattles, accompanied by an incessant and boring gobbling that may last hours. In this state of excitement, the Wild turkey even responds to human provocations, fearing that it is a possible amorous competitor, thing well known by the country children, who, for fun, make them emit violently the fateful “glo glo glo” endlessly as if it were an unrestrainable sneeze, simply emitting a plaintive whistle that seems hitting its erotic fantasy.

The dimple where the nest is placed is dug by the female under a well-hidden and sheltered bush, lined with leaves and dry grasses softened by the down the female loses while hatching the usual 10/20 eggs.

In case of danger, when surprised on the ground, the first reaction of the turkeys is a stampede at more than 40 km/h © Ron Wolf

These eggs are of considerable size, weighing even 100 g and are now considered as a delicacy, perhaps even more than those of our laying hens. Moreover, the Wild turkey is one of the few vertebrates that may reproduce by parthenogenesis, that is from eggs not fecundated by the male.

The chicks of Meleagris gallopavo are nidifugous and come to life already covered by a streaked yellowish down that camouflages them perfectly on the ground of the environment where they live.

The hatching is almost simultaneous and in the time of a few hours the brood leaves the nest to start their group life, carefully followed for some weeks by the mother hen who defends them from any danger.

Only in case of extreme necessity they take off, with a very violent and fast flapping of the short wings that causes a typical and thunderous noise © Tom Murray

The childhood spent on the ground is however a rather dangerous moment for the Wild turkey chicks who are subjected to a sometimes substantial predatory sampling. After only two weeks from hatching the chicks are able to perform their first flights and to hide during the night on the highests branches of the trees.

Meleagris gallopavo has a huge number of predators in the environments where they live wild. From the coyotes to the foxes, from lynxes to raccoons, from the snakes to the minks but also from the sky, where don’t lack owls and birds of prey of all sorts. We have not to forget the hunters who deem these birds a very coveted prey due to the particular type of hunting to which they are subject as well as for the delicacy of their flesh.

The domestic turkeys, often white or with fanciful liveries, my reach even the 40 kg of weight and have now lost completely the flight attitude © Helmut Steiner (left) and © Gianfranco Colombo (right)

As they say, the turkey has an iron stomach!

It eats everything, from fruits to any type of seeds, from the buds to the berries, from the insects to the mollusks and does not disdain to gulp down without dismembering them, reptiles and small mammals it meets along its way. Its stomach produces gastric acids so powerful to digest even pieces of metal besides the small stones it often swallows to facilitate the crushing of hard seeds it gulps down disproportionately whole.

The luckiest ones scratch around the houses of man, like these two young on duty, freeing the area by small snakes, and where stay the turkeys the vipers do not exist © Claude Rousseau

In popular tradition it is believed that the stomach of the turkeys can also affect gold, notoriously a metal that only the acqua regia can partially corrode.

As mentioned before, its food gluttony does not stop in front of grass-snakes and small snakes that it often meets during its intense scratching. In fact, in many European areas, particularly the piedmont ones, choice sites of the reptiles, the turkey is often used to fight their presence close to the farmhouses. Where turkeys go scratching, vipers and chicken snakes do not exist.

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within GALLIFORMES please click here.