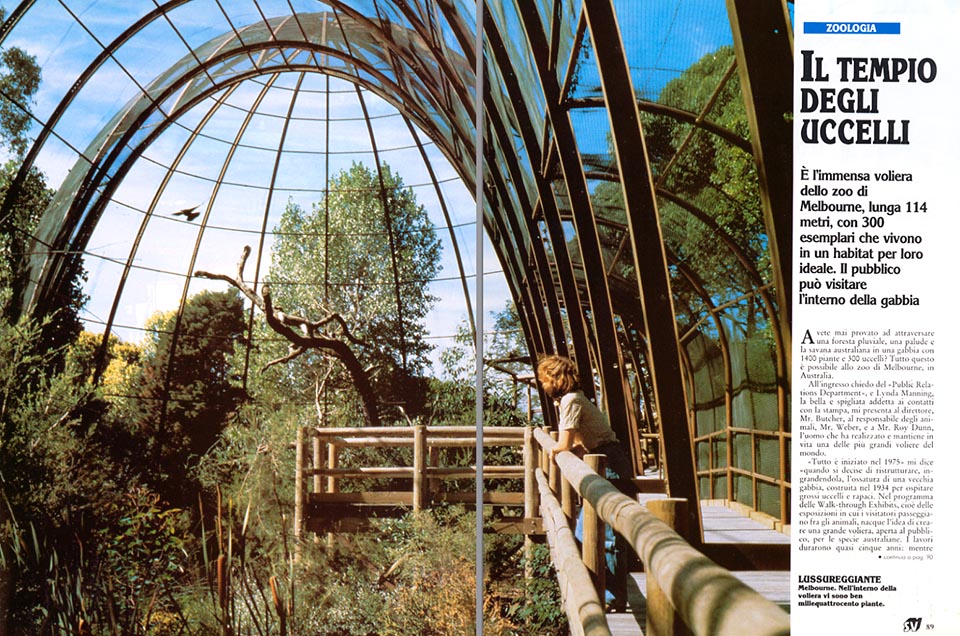

The temple of birds. It is the immense aviary of Melbourne Zoo, 114 m long, with 300 specimens that live in their ideal habitat. The public can walk on gangways through the cages.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Did you ever try to pass through a rainy forest, a marsh and the Australian savannah, inside a cage, with 1400 plants and 300 birds?

All this is possible in the zoo of Melbourne.

At the entrance, I ask for the Public Relations Department, and Lynda Manning, the handsome and smart person in charge of the relations with the press, introduces me to the director, Mr. Butcher, the responsible for the animals, Mr. Weber, and to Mr. Roy Dunn, the man who has realized and keeps alive one of the largest aviaries in the world.

“All has begun in 1975”, he tells me, “when it was decided to remodel, with an enlargement, the structure of an old cage, built in 1934 for giving hospitality to big birds, and birds of prey. In the programme of the walk-through Exhibits, that is, of the exhibitions where visitors can walk between the animals, the idea came to create a big aviary, open to public, for the Australian species.

The works lasted almost five years: while a team restored the metallic structure and positioned a net with meshes of 25 x 12 mm, in the interior were created waterfalls, small lakes and natural landscapes, with rocks and old trunks of trees.

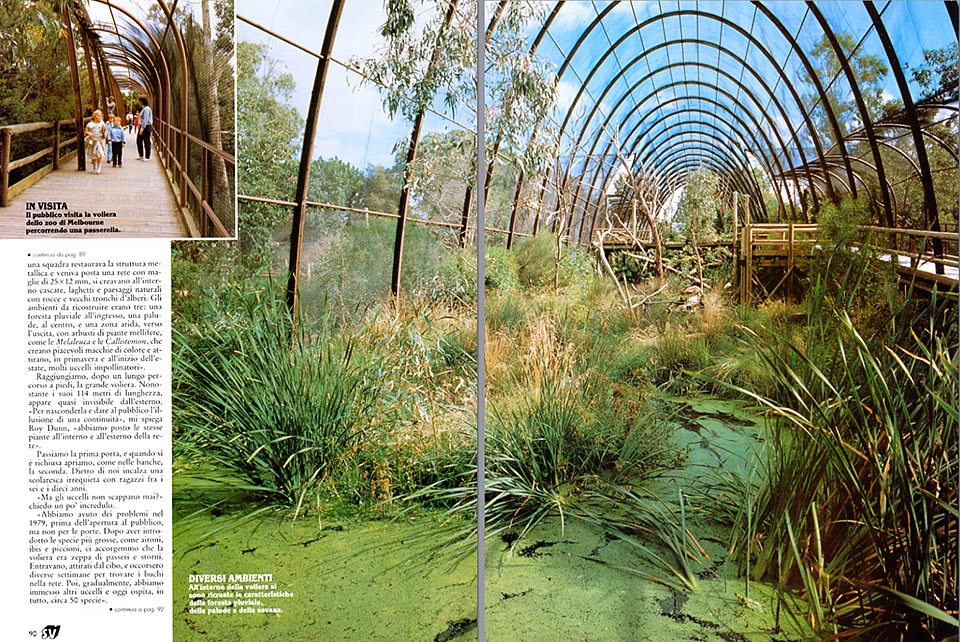

The habitats to be rebuilt were three: a rainy forest, at the entrance, a swamp, in the middle, and an arid area, towards the exit, with bushes of melliferous plants, such as the Melaleuca and the Bottlebrush (Callistemon), which create agreeable coloured spots and attract, in springtime and by the beginning of summer, many pollinating birds”.

We reach, after a long walk, the large aviary. In spite of its length of 114 metres, it seems almost invisible from outside.

“In order to hide it and to give the public the impression of a continuity”, Roy Dunn explains me, “we have placed the same plants inside and outside the net”.

We pass through the first door, and when this is closed, we open, like in the banks, the second one. Behind us, a restless group of six to ten years old students, presses.

“But the birds do ever flee?”, I ask, rather incredulous.

“We had some problems in 1979, before the opening to the public, but not for the doors. After having introduced the largest species like herons, ibis and pigeons, we realized that the aviary was full of sparrows and starlings. They were getting inside, attracted by the food, and it took several weeks to us to find the holes in the net. Then, gradually, we have put inside the other birds, and today the aviary has inside a total of 50 species.”

“But, they do not have cohabitation problems?” I ask, amazed.

“Of course”, he goes on, “we have rejected at once the predators and those which spoil the plants, and have chosen species not much territorial, and therefore less aggressive. Now and again, bigger birds break the nests of others or eat their young, but about thirty species reproduce, successfully, each year.”

“So, you risk the overcrowding?”

“Sure, the control of the delicate numerical balance between the various groups of birds, is our major concern. Seen the present population, we consider 300 the maximum quantity of subjects to be kept. Therefore, we remove periodically from the aviary the specimen in excess. Here, under the wooden footbridge, we have three main mangers, two are placed in cages and so it is easy to close them, and seize the birds.

Some time ago, we have been obliged to take off all the pigeons for an intensive treatment against the Chlamodiosis, a contagious disease dangerous also for men, and since then, as a prevention, we impregnate, periodically, the food with antibiotics. Every year, in the aviary, transit at least 100.000 students, and we do not want to meet any risk.”

While I thank him, and take some time to shoot some photos, I am, indeed, knocked down by a group of at least two hundred boys. Between 10 and 12 in the morning, it’s an uninterrupted movement of school boys.

Teachers are accompanied or replaced by a staff of 14 specialized instructors, who work full time in the zoo, and there exist seven halls, always crowded, for stages at every level. They insist in order that the boys touch skins, horns, bones, and handle, without stressing them, living animals, such as opossums, lizards, and snakes.

During the visit, they have also a “school work”: they must complete, with personal notes and answers, an illustrated booklet and some questionnaires. The function of the zoo, and of the aviary, is to sensitize them through the direct knowledge of animals and plants, to the respect of this naturalistic patrimony, which rates between the richest and best protected in the world.

SCIENZA & VITA NUOVA – 1984