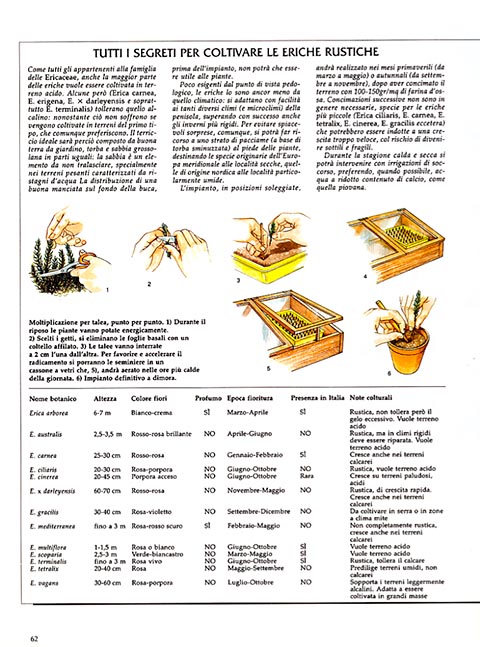

A small flower for all seasons. There are 1.900 species of heather, 95% from South Africa, great horticultural potential. They blossom not only in winter, as commonly believed, but in all seasons.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

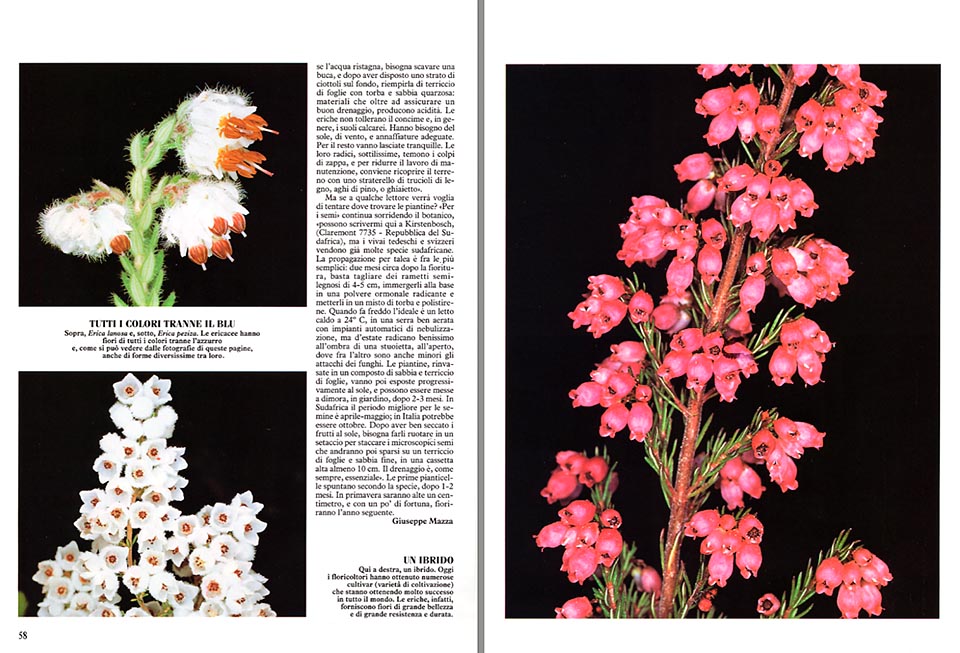

For flowering, the Heath (Erica herbacea = Erica carnea), has kept the most rigorous months. It is not unusual to find its very charming clusters of pink or red small bells ogling among the fresh snow, and seen that, beyond the cold, it resists well also to the drought, it has become, in our countries, the ideal plant for the cemeteries.

Suitable for an entirely seasonal “worship”, not to say daily, and to be miserably abandoned close to a gravestone.

Cultivars and hybrids have aimed a bit the shot, propagating with success the heaths in the verandas and in the “winter balconies”, also because, from December to February, there are not so many flowers around, and recently, for the rocky gardens, people has been looking also to the exotic species with vernal and summery flowering.

European nurseries already produce 50 millions of them each year, but in Italy, even if the Mediterranean climate is paradoxically one of the most suitable, the heaths are still to be discovered.

They are mistaken for the Calluna vulgaris, a species of the same family, synonym of moor and poverty, with a petaloid calyx longer than the corolla, and almost nobody knows that there are more than 650 botanical species of them, South African for the 95%, with inflorescences often showy and an enormous horticultural potential.

“But eucalypti”, Deon Kotze, specialist in heathers in the famous botanical orchard of Kirstenbosch, comments, “very few genera own a similar abundance of species. And, above all, their geographic concentration is amazing: 600 species in the Cape Province, smaller than Southern Italy, against the only 14 present in Europe.

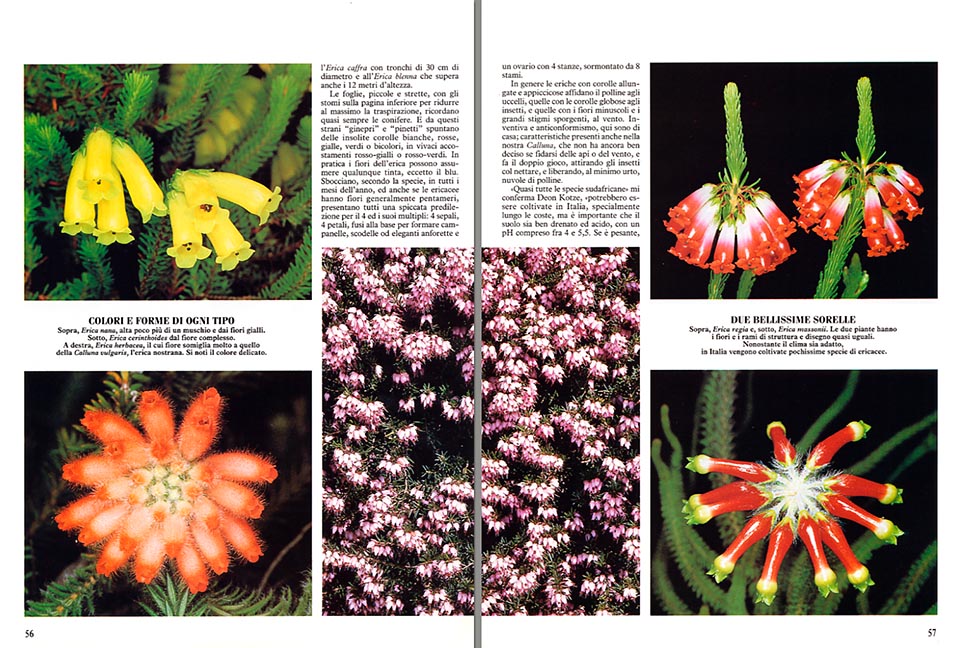

Incredible proliferation, incredible morphological modulations on only one theme. Species which often grow up, side by side, in an infinity of micro climates, adapting to every habitat, from the sea level to an altitude of 2.500 metres, from the dry regions to the “feet in the water”, with woody trunks and prostrate gait, shrubby or arboreal. We go from the Erica nana, not much taller than a moss, to the Erica caffra, with trunks of 30 cm, and to the Erica blenna, which overcomes a height of 12 metres.

The leaves, small and narrow, with the stomata on the inferior side, in order to reduce at the maximum extent the transpiration, recall almost always the conifers. And from these odd “junipers” and “small pines”, come out unusual white, red, yellow, green or bicoloured corollas, in lively red-yellow, or red-green matchings.

Practically, the flowers of heaths can assume any colour, but blue.

They blossom, depending on the species, in all the months of the year, and even if the ericaceae (the family which unites the heathers to the azaleas, the strawberry tree and the bilberries), have flowers usually pentamerous, present all a marked predilection for the number 4 and its multiples: 4 sepals, 4 petals, merged at the base to form little bells, bowls or fashionable little amphorae and an ovary with 4 rooms, surmounted by 8 stamens.

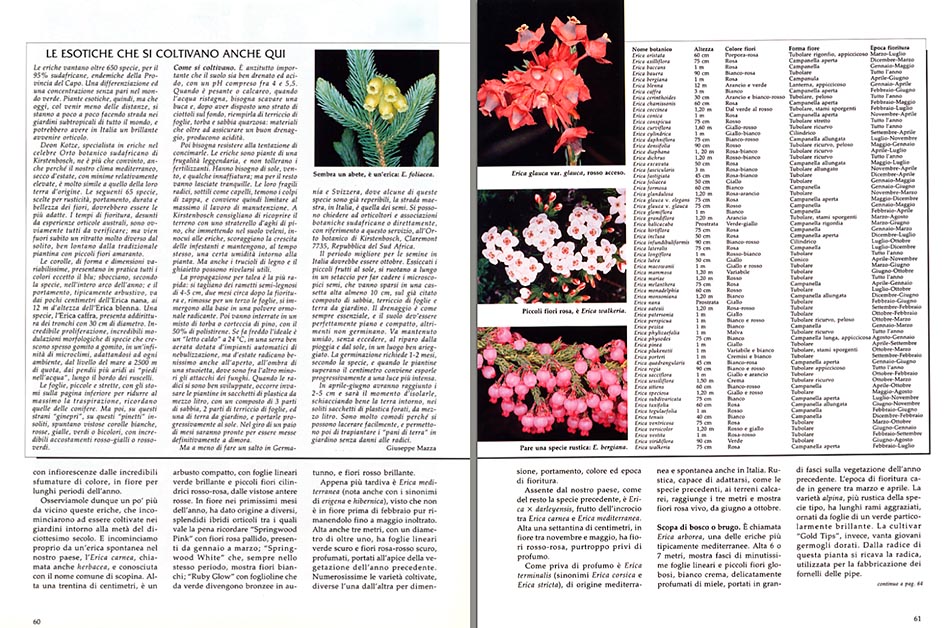

The anthers, examined with the microscope, are real jewels: each species has its own exclusive “design”, and the two small cells from where the pollen goes out, present often a couple of puzzling small wings. Nobody knows what is their use, but they have certainly an important part in the various strategies of reproduction.

Usually, the heaths with longer and sticky corollas, entrust the pollen to the birds, those with globular corollas, to the insects, and those with the very small flowers and large, protruding, stigmata, to the wind.

Inventiveness and non-conformism are here of the family; characteristics which are present in our Calluna, which has not yet well decided if to rely on bees or on the wind, and so is double crossing them, attracting the insects with the nectar, and releasing, after the smallest shock, clouds of pollen”.

“Almost all the South African species”, Deon Kotze confirms to me, “might be cultivated in Italy, especially along the costs, but it is important that the soil is well drained and acid, with a pH between 4 and 5,5.

If it is heavy, if the water stagnates, we have to dig a hole, and after having placed a layer of pebbles on the bottom, to fill it with a mould of leaves with peat and quartzy sand: materials which, beyond assuring a good drainage, produce acidity.

Heaths do not tolerate the manure, and, in general, the calcareous soils. They need sun, wind, and adequate watering. For the rest, they must be let alone. Their roots, very thin, cannot stand the hoeing, and, in order to reduce maintenance work, it’s convenient to cover the soil with a light bed of wood chips, pine needles, or gravel, thus maintaining a certain humidity and discouraging the growth of infesters.”

“Am sure”, I interrupt him, “that many readers will be longing to try, even if, then, they will not know where to find them.”

“For the seeds”, he goes on, smiling, “they can write to me, here in Kirstenbosch, but German and Swiss nurseries sell already many South African species.

The propagation by cutting is very simple: about two months after the flowering, it is sufficient to cut off some small woody branches of 4-5 cm, dip their base in an hormonal rooting powder and place then them in a mixture of peat and polystyrene. When it is cold, the best thing is a bed heated at 24 °C, in a well ventilated greenhouse, with automatic nebulizing systems, but in summertime they root quite well on the shade of a small mat, in the open air, where, on the other hand, fungi attacks are lesser.

The small plants, potted in compound of sand and mould of leaves, must be then progressively exposed to the sun, and can well be settled in place, in the garden, after 2-3 months.

In South Africa, the best period for seeding is April-May; in Italy should be October.

After having dried up well the seeds under the sun, you have to whirl them in a sieve in order to separate the microscopic seeds which then will be scattered on a loam of leaves and then, sand, in a small case tall at least 10 cm. Drainage is, as usual, essential, the soil must be well flat and compact.

The first small plants come out, depending on the species, after 1-2 months. By springtime, they will be tall one centimetre and, with some luck, they will bloom the following year.”

SCIENZA & VITA NUOVA + GARDENIA – 1990

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within the ERICACEAE family please click here.