Family : Octopodidae

Text © Sebastiano Guido

English translation by Mario Beltramini

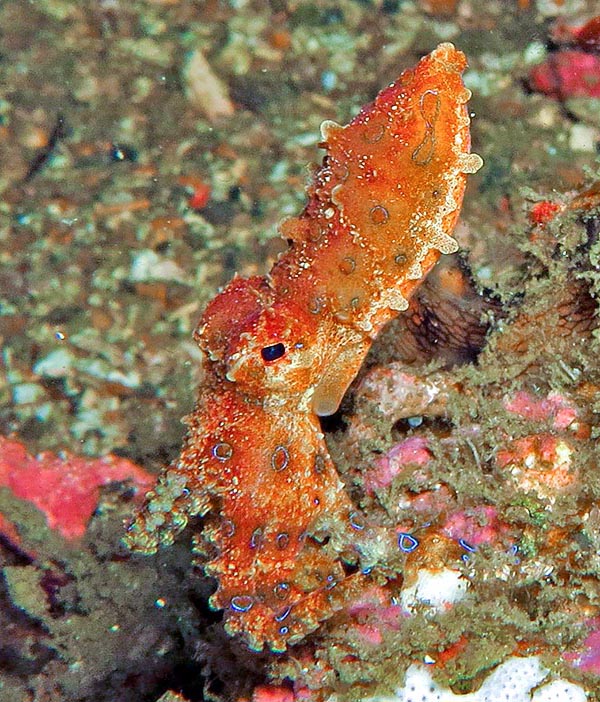

The Greater blue-ringed octopus (Hapalochlaena lunulata) loves warm waters. Indicatively, is present, patchy, in the reefs of Australia, Papua, Solomon, Indonesia and Philippines up to Japan © S. Guido

The Greater blue-ringed octopus (Hapalochlaena lunulata Quoy & Gaimard, 1832) belongs to the class of the Cephalopoda, marine molluscs with shell absent or very reduced, order of the Octopoda and to the family Octopodidae, octopus with eight arms, sac-like body, head equipped with strong beak, very developped eyes and a membrane that unites at the base the tentacles, usually endowed with a double row of suckers.

The etymology of the genus Hapalochlaena comes from the Greek words “hapalo” (delicate) and “chlaena” (cloak similar to the chlamys). Hence it describes a delicate epidermis as delicate is the octopus wearing it, who shows the precious light blue patterns only during the important moments of its life.

The name of the species lunulata, in Latin resembling a small crescent, described the shape of the rings (even if actually the lunula of the Roman senators had the shape of a crescent).

The Italian name (Polpo dagli anelli blu) evidences the most striking part of the livery: those blue rings it displays during the courting, when in fear and when upset.

Zoogeography

It is a warm waters octopus, present only, patchy, in the reefs of Australia, Papua, Solomon, Indonesia, Philippines and Japan, even if not excluding the possibility to encounter it also in adjacent zones.

Ecology-Habitat

The Hapalochlaena lunulata lives in close contact to the bottom and it is possible to meet it from the decimetres of the tide pools up to the depth of about fourty metres.

The extreme mimicry and the small size lead us to believe that during the next years with the progress of research systems and the increase of searchers, interesting developments of the knowledge of the habitats frequented will occur.

Presently, rightly for the two factors cited, besides in the rock pools it is easier to find them on barren, pebbly seabeds having few oases where they can hide. Even if the reefs might be full of them, in fact, they would have there too many hideouts and it would be necessary to have Argo’s eyes to be able to see any of them.

It lives in touch to the bottom, in low waters, not more than 40 m, surely in the rocky pools, where it’s easier to see it © Sebastiano Guido

Morphophysiology

The tentacles do not exceed the ten centimetres of length, as well as the body whilst the average, in the rare specimens met, reaches roughly the half. The weight varies from ten to hundred grams.

The mollusc, when found on the bottom, is clinging to something, pretending to be an integral part of the same. In those instances, the body is recognized due to the shape of the sac most of the time ending in a point and often edged with a lace of small excrescences.

It can be, tentacles included, 20 cm long but usually measures about half. When excited for the marriage or when disturbed, on the body appear, almost fluorescent, some blue rings emphasized by reddish spots. A way for being noted or as a remainder to predators that its bite is very venomous © Sebastiano Guido

Its colouring is tuned to the environment, with very sheer small circles that, rather than see them, may be guessed. Only the hawk’s eye of a guide, who knows where to search, may be able to find it, often only after long research. Once the specimen is found, in order to have it exhibiting the splendid blue circles that embellish its image, we have to proceed closing our hand in a fist and, when close to the subject, stretch out the fingers suddenly. The fright induces the gastropod to a threatening attitude that consists in the exhibition of the blue rings: the same circles that, shown during the period of oestrus for courting a female, have allowed the guides to localize and memorize the territory inhabited by the mollusc.

Here it is, resembling a small sac, in one of its mimetic liveries, thanks to chromophores of various colour that expanding or dwindling create instantly environment colours and patterns © Sebastiano Guido

Eight spindly tentacles start from the neck, that closes the cephalic sac. Over them, two “big” eyes look around with an enigmatic look the surrounding world. At the centre of the tentacles a small horny beak, dispenser of death. It is connected to the salivary glands, where some species of symbiont bacteria produce the lethal tetrodotoxin.

The skin is a miracle of nature: equipped with nervous terminations that allow it to flex out at will protrusions and warts, is endowed of particular cells, the chromatophores.

Each one of these “colour bearers” has a different colour and, if solicited by the nervous system of the octopus, expands showing its own colour. If, for instance, the gastropod would decide to tune to a yellow bottom it would expand only the yellow chromatophores and the same would be done, with other chromatophores, to even out whatever colour and drawing of the bottom.

Besides mimetizing the octopus, the colourations are a language of which we, for the moment, are able to understand only a “scream”: that transmitted by the blue rings.

In nature the bright colours are warnings for informing the observer that the carrier is not just a simple bite. Even if our octopus might run away from the mouths that should have swallowed it by moving on its own tentacles, and leaving the “whale” agonizing, our new Jonah prefers to avoid frights and maybe some bite that might hurt it, hence it waves the banner with the circles that warns for the danger, hoping that every predator is able to read it.

Besides to avoid to become food, in order to survive is necessary also to eat and a deadly toxic cocktail is the perfect weapon for getting a lunch. To compensate the escaping speed of the victims (that could get far away considerably in a few seconds, perhaps ending up prey of some rascal hidden in the neighbourhood), the venom the octopus injects is so strong to paralize and kill in milliseconds. The prey is dead even before having had any escaping reactions.

It has been calculated that the venom of the Hapalochlaena lunulata, (a mix of neurotoxins where the tetrodotoxin does the lion’s share) injected in a quantity of 8 µg (eight millionths of a gram) per each pound of body weight of a person, is sufficient to kill her.

Difficult to distinguish it on this ascidia smaller than a span. Who would say that such a small being may rapidly kill a human? Its strong weapon is the tetrodotoxin, venom produced in the salivary glands by symbiont bacteria. Eight millionth of gram per kilo are sufficient to kill the importunates © Sebastiano Guido

For this reason the unfortunate that should get a bite, depending on the quantity of venom received, would have available an agony not longer than a couple of hours, with progressive paralysis of the whole body just after 15 minutes from the unlucky event. The impossibility of breathing, with consequent hypoxia, might lead also to the cardiac arrest.

Under the water hardly the victim would have any chance of scraping through it; better luck might have only he who had been bitten by an octopus touched by him in a tide pool. In this case, the timely intervention of a rescuer (able to keep alive the victim with the cardiorespiratory resuscitation until when he reaches a medical centre that should continue effectively these therapies) might perhaps avert the tragedy.

Crustaceans, molluscs and fishes are surprised while sleeping and do not even realize that they are dying. The venom paralyzes and kills preys in milliseconds © S. Guido

As antidotes to the venom do not exist, this is the only possible care for keeping alive the unfortunate until when (after 15-24 hours), the toxin modifies spontaneously and ends its action. If, after this time, the unfortunate has been able to survive, he will gradually resume his vital functions, without reporting aftermathof any kind.

Ethology-Reproductive Biology

The Hapalochlaena lunulata nourishes mainly of crustaceans, and in particular shrimps and crabs, but seizes also molluscs and even fishes, surprised while resting during the night hours.

Here, crouched, has noted a danger and tries to avoid it. It has taken an irregular mimetic contour and activated the chromatophores. Venom and mimicry are not enough. Also Hapalochlaena lunulata has its predators: they are mainly morays and groupers that can overcome it without being bitten perhaps immune to the ingestion of venom © Sebastiano Guido

Its predators are especially morays and groupers that are able to overcome without being bitten and that appear to be immune to the ingestion of its venom. Towards man it is usually shy, but might bite if afraid and prevented to escape.

For the mating, the male, smaller than the female, binds tenaciously (from behind) to the cephalic sac of the partner introducing in its pallial cavity a small sac of spermatophores. Later on, these will be utilized by the female to fecundate the eggs.

Once danger has past it has moved to a more uniform support and is relaxing. The blue circles and the reddish zones fade whilst the protuberances disappear © S. Guido

To deliver it the gametes, the male uses the third right tentacle (the hectocotylus) with which takes them off from its own Needham pocket to give them to the partner. The approach from behind suggests the possibility that the lady has cannibal instincts, as the cannibalism is a common practice in many species of octopuses and there is no reason to think that the Hapalochlaena lunulata does not use it.

Presently the resilience and the vulnerability index are unknown.

Synonyms

Octopus lunulatus Quoy & Gaimard, 1832.

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within the MOLLUSCS please click here.