” Feminist ” Australian plants. Female organ deflowers the males, and offers pollen in their place. Inflorescences similar to fringes, tooth brushes or fireworks. 250 species and many hybrids.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

The flowers are just the sexual organs of the plants.

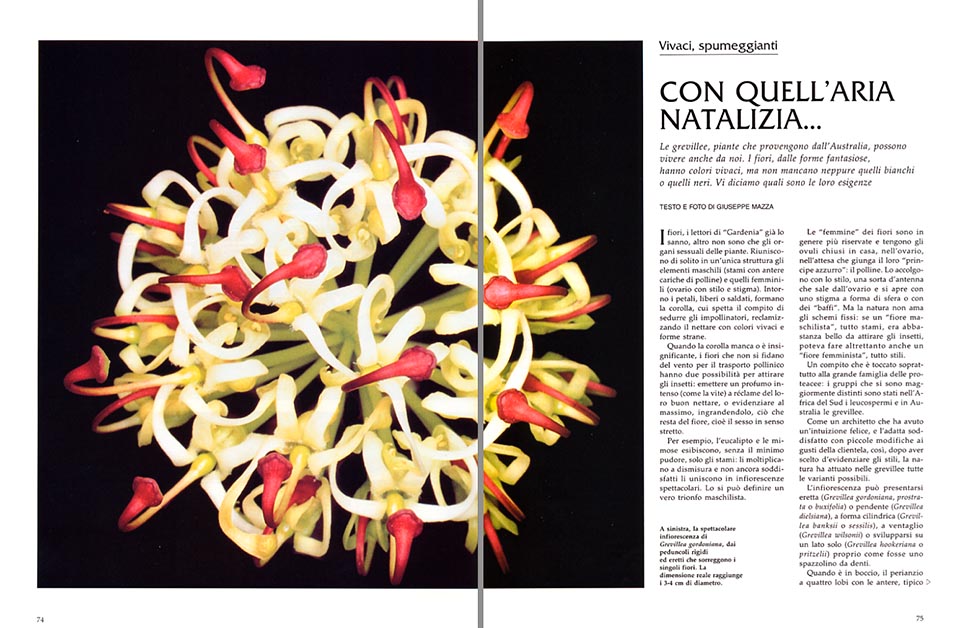

They normally assemble in a unique structure the masculine elements (stamens with anthers loaded of pollen), and the feminine ones (ovary with style and stigma). Around, the petals, free or united, form the corolla, which is in charge of seducing the pollinators, advertising the nectar with lively colours and unusual forms.

When the corolla is absent, or is negligible, the flowers, which do not rely on the wind for the transportation of the pollen, have two possibilities for attracting the insects: either to emit an intense scent (like the vine), for advertising their good nectar, or to point out, at the maximum, enlarging what remains of the flower, that is the sex in the strict sense.

We have already seen the eucalyptus and the mimosas, which exhibit, absolutely shamelessly, only the stamens: they multiply them to the excess, and, not yet satisfied, they assemble them in spectacular inflorescences. A real sexist triumph.

The females of the flowers are normally more discreet, and keep the ovules closed at home, in the ovary, waiting for the Charming Prince, the pollen, to come.

To welcome it, they emit the style, a sort of TV antenna, which goes up from the ovary and opens with a stigma, with the shape of a sphere or of a whisker, exactly like every respectable antenna.

But nature does not love static models, and much before the recent feminine revendications, has thought that is a “sexist flower”, all stamens, was beautiful enough to attract the insects, then it could do the same thing also with a “feminist flower”, all styles.

The duty of bringing ahead this “subject”, has been assigned mainly to the great family of the proteaceae, and the groups which have more distinguished, have been, in South Africa, the pincushions, and in Australia, the grevilleas.

Like an architect who has had a lucky intuition, and adapts it, satisfied, with minor modifications, to the taste of the customers, so, after having chosen to evidence the styles, the nature has put in effect all possible variations in the grevilleas.

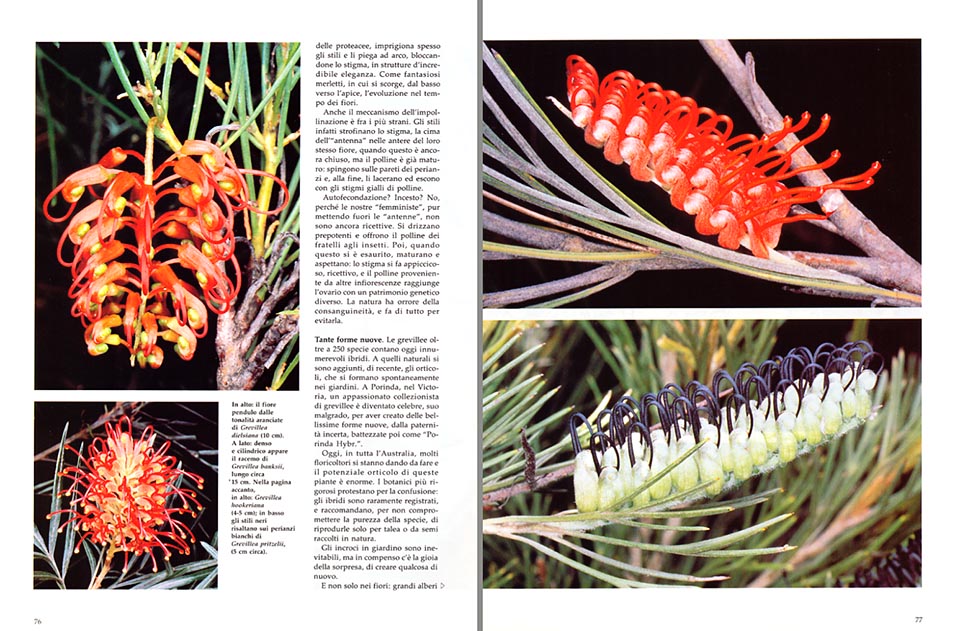

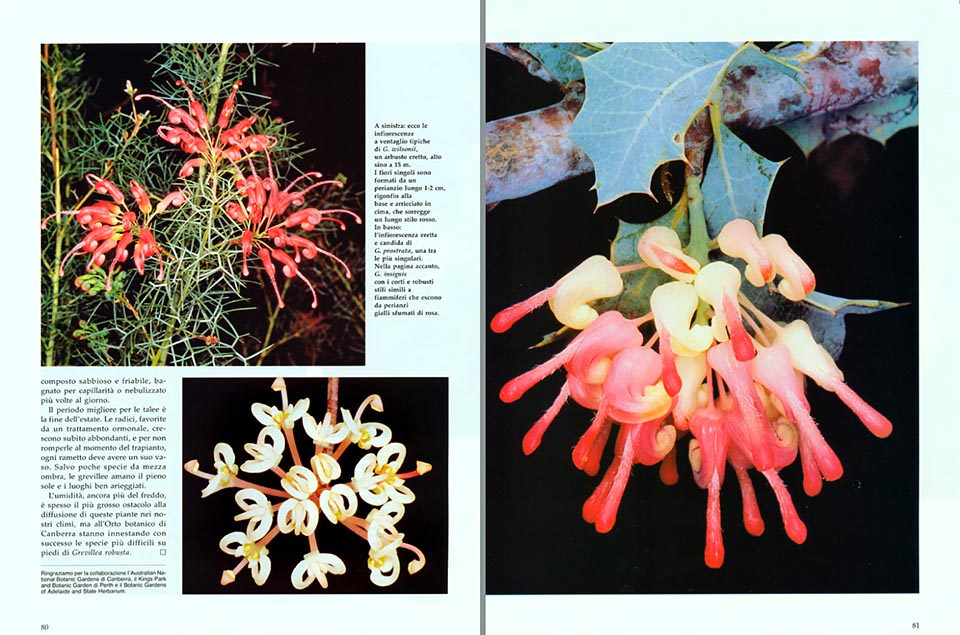

The inflorescence can appear upright (Grevillea gordoniana, Grevillea prostrata or Grevillea buxifolia), or hanging down (Grevillea dielsiana), cylindrical (Grevillea banksii or Grevillea sessilis), fan-like (Grevillea wilsonii), or develop on one side only (Grevillea hookeriana or Grevillea pritzelii) as a tooth-brush.

When in bud, the four lobed perianth with the anthers, typical of the proteaceae, often keeps inside the styles, and bends them like a bow, blocking the stigma, in structures of incredible elegance. Fanciful laces, where we can perceive, from the bottom to the apex, the evolution of the flowers in the time.

Also the mechanism of pollination is among the strangest. The styles rub the stigma, the top of the “TV antenna”, on the anthers of their same flower, when this is still closed, but the pollen is already ripe. It’s the moment of the “Dance of the bows”, the one where the “girls”, folded as a bow, push on the sides of the perianths. By the end, they lacerate them and get out with the stamens, yellow of pollen.

Self-fecundation? Incest?

No, because our “feminists”, even if drawing out the “antennas”, are not yet receptive, they have not yet switched on, in short, the “TV set”, which is kept down, in the ovary. The genetic “programme” of their flower does not interest them, and they prefer to wait for other “emissions”.

They stand up, overbearing, like males, and offer their brothers’ pollen to the insects.

Later on, when this is finished, they ripe, and like all the “girls” of the world of the flowers, they switch on their “TV set”, and wait.

The stigma becomes sticky, receptive, and the pollen coming from other inflorescences, reaches the ovary with a different genetic patrimony.

The nature hates consanguinity, and does its best to avoid it.

On the contrary, once switched on the “TV set”, the grevilleas are wide open also for far away “networks”, and, besides 250 species, they number today countless hybrids.

To the natural ones, have joined recently, the horticultural ones, which form, spontaneously, in the gardens.

In Porinda, in the state of Victoria, a passionate collector of grevilleas, has become famous, unintentionally, for having created some very nice new forms, with uncertain fatherhood (this is the risk of free loves), christened, later, as “Porinda Hybr.”

Nowadays, in the entire Australia, many floriculturists are bestirring themselves and the horticultural potential of these plants is enormous.

The most rigorous botanists protest for the confusion: the hybrids are seldom registered, and recommend to reproduce them only by cutting, or by seeds collected in the wild, in order not to compromise the purity of the species.

The garden cross breeding are unavoidable, but, in return, there is the joy of the surprise, to create something new.

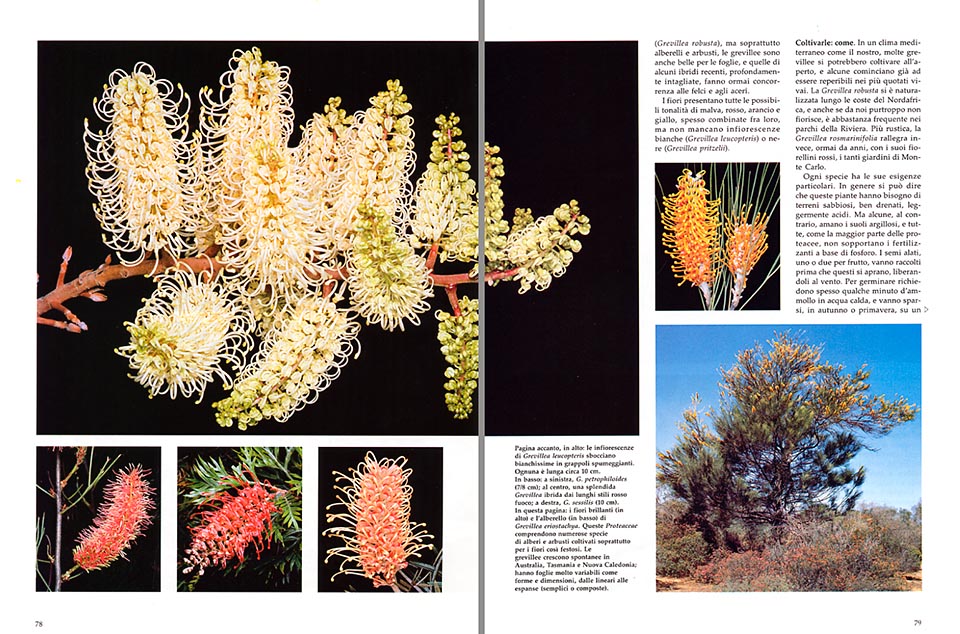

And not only in the flowers: big trees (Grevillea robusta), but, mainly, saplings and bushes, the grevilleas are also beautiful for the leaves, and those of some recent hybrids, deeply indented, now compete with the ferns and the maples.

The flowers present all the possible tones of mauve, red, orange, and yellow, often combined between them, but there are also completely white inflorescences (Grevillea leucopteris), or black (Grevillea pritzelii).

In a Mediterranean climate like ours, many grevilleas could be cultivated in open air, and some of them begin already to be available in the nurseries.

The Grevillea robusta has naturalized along the coasts of North Africa, and even if in our country is seldom in flower, is rather frequent in the parks of the Riviera.

More rustic, the Grevillea rosmarinifolia gladdens, since years, with its small red flowers, the gardens of Monte Carlo.

Each species has its own exigencies. As a rule, we can say that these plants need sandy soils, well drained, slightly acid. But some of them, on the contrary, love clayey soils; and all of them, like most of the proteaceae, do not stand the fertilizers based on phosphorus.

The winged seeds, one or two for each fruit, must be collected before they open, freeing them in the wind.

To germinate, they often require some minutes of immersion in warm water, and must be spread, in autumn or spring, on a sandy and crumbly compound, watered by capillarity or nebulized several times a day.

The best period for the cuttings is the end of summer. The roots, supported by a hormonal treatment, grow up, at once, abundant, and in order not to break them at the time of the transplantation, each small branch must have its own pot.

Apart few mid-shade species, the grevilleas love the full sun and the well-aired locations. The humidity, more than cold, is often the impediment to the diffusion of these plants in our climates, but in the Botanical Orchards of Canberra, they are grafting, successfully, the most difficult species on feet of Grevillea robusta.

Besides insect, these odd “feminists”, have, by this time, seduced also men, and their horticultural adventure is just at the beginning.

GARDENIA -1988