Text © DrSc Giuliano Russini – Biologist Zoologist

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Not seeing in this Crocodylus niloticus some dinosaurs ancestral characters is difficult © Giuseppe Mazza

Class: Reptilia.

Subclass: Archosauria.

Order: Crocodylia.

Suborder: Eusuchia.

Family: Crocodylidae.

Subfamily. Three groups: Crocodylinae, Alligatorinae and Gavialinae.

The members of the family of the Crocodiles (Crocodylidae) form a small group, relatively homogeneous and are the only survivors, along with the birds, of the vast evolutionary line of the Sauropsids (Sauropsida).

This is a family known since the Upper Cretaceous (Mesozoic era), with specimens which have left several fossil traces in all the continents, including most of Europe and of North America, in the Old and New World. None of the old forms was particularly differing from the present ones and it seems therefore the type “crocodile” has formed since very long time. Then, different lines have originated, independently, close to short snouted forms, called “brevirostral”, long snouted forms, “longirostral”. But this is a typical adaptation, which profits by the phenotypical plasticity, caused by the piscivorous diet adopted by the species and not by a generic evolutionary tendency, even if the ancestral forms, the Triassic Protosuchids (Protosuchia all had a very short snout.

Among the three recognized subfamilies, the Alligatorines (Alligatorinae) are considered as the most primitive, whilst the Gavialids (Gavialinae), members of a unique genus known since only the Miocene, form a distinct group, which may be possibly stand closer to the Jurassic Telosaurids (Telosauridae) than the other crocodiles.

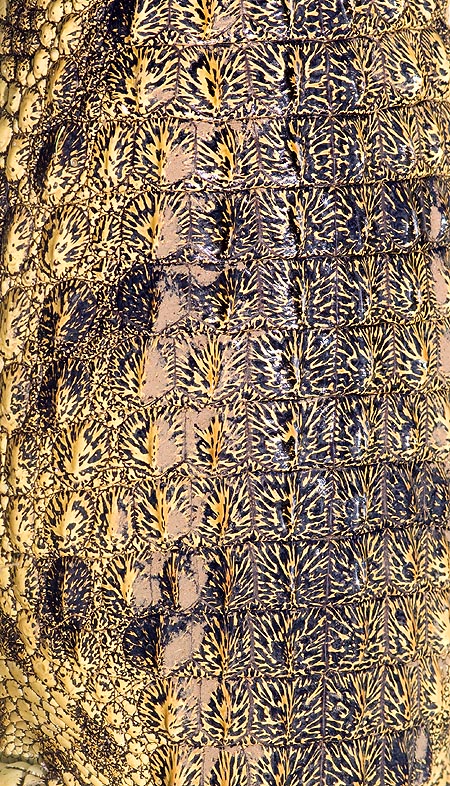

The overall appearance of the crocodiles, big head with long and robust jaws, heavy body, robust legs and thick, laterally flattened, tail, renders them one of the reptilians better known to the inexperienced persons, also because they are often present in the zoological gardens, aquatic parks and in many natural reserves, not to forget the private individuals homes, where at times they are the origin of deadly occurrences. They have an armoured skin with scales, subject to change, with a grey sand- dark green colour. The eyes are very close and protruding, placed on top of the head, and the nostrils, equipped with valves, are located at the front end of the snout.

The strong armor and the keeled scales lead to think to the Mesozoic Era © Giuseppe Mazza

The flattened tail and other particularities, such as the ears provided with a mobile pinna, the secondary bony palate, etc., are all indications of an aquatic and terrestrial life at the same time.

Although being descendants of biped terrestrial forms (dinosaurs) and perhaps at the beginning also partially arboreal, the present crocodiles are semi-aquatic tetrapods: they hunt and mate in the water, take shelter there, and usually come to the land only for basking or for laying the eggs.

However, at least some species has the habit to dig deep dens on the banks, for spending, depending on the needs, some periods of summer or of winter, or resting, by day as well as by night.

All crocodiles are oviparous.

The females lay from 15 to 95 eggs on the banks: some, in simple holes dug in the sand, others at the centre of a relatively high mound, made with a mixture of mud and vegetal debris. They are useful, with their fermentation, for generating the necessary warmth for the right incubation of the eggs, and it seems that in this case the females do remain in the vicinities for surveying the nest.

During the first half of the seventies of the last century, the herpetological American biologist Dr. H.B. Cott, has shown by means of field observations which had started in the sixties, how much important is such form of watch in the case of the Nile Crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus). In the Uganda national Park, where the scientist was working as wildlife conservator, he observed that the quantity of the nests destroyed, normally going from 40 to 50%, might even increase to the 70-100% where the excessive amount of tourists did disturb the females during the reproductive time. The author, among other things, did note that the main predators of the eggs are the baboons, the hyenas and the monitor lizards, are responsible, just them, of about the 80% of the damages caused. Obviously, we are talking of not watched nests as, when the mother is present, a hyena and, much less, a baboon or a monitor lizard would not have any chance!

All crocodiles are carnivorous, and do not disdain the carrions and the various residuals (necrophagous), but their preys vary depending on their size, and therefore on the age and the species. The short-snouted species (brevirostral) nourish willingly of terrestrial animals, at times even of rather big mammals.

The eye of a night swimming Crocodylus niloticus cannot leave indifferent © Giuseppe Mazza

They seize them by surprise in the shallow water and, with a precise and instantaneous snap, make them fall with a very fast torsion of the whole body. Then, they drag them to the bottom in order to drown them.

They calmly tear them and when there are some difficulties, they wait for them to become more or less tender or decomposed for then eating them.

In fact, it is often matter of preys of a certain size, which fight for surviving, such as gnus, zebras, antelopes and gazelles, which go to water along the rivers where these reptilians stand in ambush, during their social seasonal migrations or during the daily wandering looking for food.

The highly efficient hunting technique of the crocodiles has remained mysterious until about the half of the sixties of lat century, when, by means of the cinematography associated with the photography, the zoological biologists and the documentarians have been able to clarify, at least in part, its mechanisms.

However, also in this case, as usual, most of the diet is formed by preys of a much more modest size of what is commonly thought. The young individuals and the smaller species nourish mainly of aquatic invertebrates, big insects fallen into the water, amphibians, nestlings of birds and, of course, of fishes (cichlids) which they can grasp. The long-snouted forms (longirostral) are markedly piscivorous, but never in an exclusive manner, even if, generally, do not tend to seize terrestrial preys.

The crocodiles, which are perfectly comfortable in the water, where they swim with strong lateral undulations of the tail and the legs folded along the body, when on the soil are clumsy, when they have to hoist themselves laboriously on the bank or the bask lying on their belly. But this is only an impression, as also the biggest specimens are able to move quickly on the ground, with the body kept much higher than the saurians and the legs that move on a practically vertical posture. The structure of the pelvis, anatomically closer to that of the birds than to that of the reptilians, explains this type of walk, justified, talking in an evolutional and paleontological way, by the origins of the family.

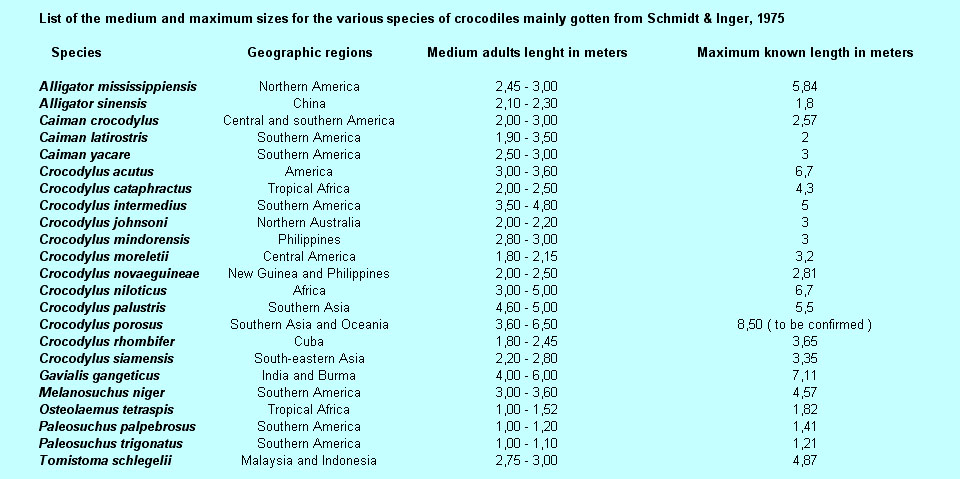

The size of the crocodiles fluctuates between a wide range of values, as it may be seen in the scheme below:

Dimensions and origin zones of the species belonging to the Crocodylia order

In any case, if considered as group, they are, without any discussion, the greatest extant reptilians and the weight of some seized individuals exceeds the ton!

Once adult, most of the crocodiles do not have foes, but the man with firearms or the spears, even if the Lions (Panthera leo), when upset or menaced, do not hesitate in attacking them. And, for the sake of the truth, even the greatest crocodile must be careful not to disturb too much the Hippos (Hippopotamus amphibius), seen that these animals do not tolerate in any way their harassment, especially hen they see their own progeny in danger. As it happens for the sea turtles, the eggs and the much young specimens become victims of various predators to which we have to add, in this case, also the congeners and the adult conspecifics.

The specimens included between the meter and the meter and a half, and therefore also the adults for some species, are at times eaten by the big Boids (Boidae), for instance, as we have seen in the Serpentes, by the anacondas that, being semi-aquatic, often do attack the small caimans and the alligators, menaced also by the Jaguars (Panthera onca), whilst the crocodiles of this size may form a meal for the Lions (Panthera leo) and the Leopards (Panthera pardus), and the gavials must deal with the Tigers (Panthera tigris) and the Asian leopards.

The American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) is the New World best known species © Giuseppe Mazza

After this general introduction on the family of the Crocodiles (Crocodylidae), we shall treat in a more detailed way the subfamilies in which it divides, and then outline the ecology and the compared physiology of the group, treating the typical aspects of these animals.

It should be noted that, whilst for the Chelonia, the Serpentes and the Sauria, the quantity of studies done, both on the field and in controlled environment (terrarium-vivarium in a zoological garden or and aquatic park) is conspicuous, for the members of the group of the crocodiles, the knowledge about their ethology, physiology and ecology are rather poor, seen the size and the dangerousness characterizing them, their wary nature and their capacity of spending a lot of time underwater.

Subfamily of the Crocodylines

(Crocodylinae or Crocodilinae)

The crocodylines are spread in almost all the tropical zones of the planet, but a small part of southern America, and do not expand in the subtropical zones, excepting one only species which reaches the Florida.

Of the 13 species of which presently consists this subfamily, 11 do belong to the genus Crocodylus. Among these ones, four live in Central America and in the northern part of South America, two in Africa, and five in the zone located between India, Philippines and northern Australia.

The American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) is the best known species in the New World. This huge animal, which in some rare specimen may exceed the 6 m of length, lives in the swamps and in the large water streams, and does not hesitate in venturing also in the sea. Due to this reason, it is met in the north-western coast of South America, starting from northern Peru and in Central America, at the southern tip of Florida and in the Antilles. More active and aggressive than the alligator, with whom it cohabits in Florida, this animal attacks big preys, but is not considered as a menace for the man, provided it is not disturbed.

The Crocodylus intermedius, of the Orinoco basin, reaches the same size of the previous species (with the gavial and the saltwater crocodile they are the greatest extant crocodiles), but with a much thinner and elongated snout, possibly due to its piscivorous diet. But this, very few information are available about its behaviour.

The Cuba Crocodylus rhombifer spreads up to th Pine Island, in French New Caledonia © Giuseppe Mazza

The other two American members of the genus, smaller, are rare and are localized in the swamps. They are the Crocodylus moreletii, at home in south-western Mexico, in Honduras and in Guatemala and the Crocodylus rhombifer of Cuba. This second species, however, extends (unique case) also up to the Isle of Pines, in the French archipelago of the New Caledonia in the Pacific Ocean.

The most famous of the proper crocodiles is, without any doubt, the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus).

Spread practically everywhere south to Sahara, at least till a recent time (the seventies of the last century), it has nowadays disappeared in many locations, especially in southern Africa, due to the intense hunting related to the leather industry.

In the past times, it had a remarkably ampler distribution. Some small population was present, until the second half of the seventies of the last century, in some “gueltas” (oasis area, formed by stagnating water, often surrounded by rocks, where nomadic peoples, such as the Sahrawis and the Tuaregs, installed temporary camps) of southern Sahara (Ennedi: system of mountains whose particular characteristics are its bizarre and impressive formations of Tassilian formations, which, along hundreds of kilometres originate a maze of canyons, gorges and narrow passages, where hide cool and crystal clear gueltas) and central (Tassili and Hoggar, mountainous and rocky systems of the Berber highlands of North Africa and Chad), reflects the fact that these animals did occupy good part of northern Africa, if not the whole of it, before the same did transform in desert. They were still found, in historical times, in the Mediterranean area where they did arrive by following the course of the Nile and even in Syria.

The Cocrodylus niloticus is robust and active, with a remarkable adaptability. It is content with little (the specimens of the “gueltas” of the Ennedis, which, to say the truth, are always small, nourish of insects or of terrestrial and aquatic invertebrates), but are always ready to attack also big preys, such a desert Oryx while watering.

It is a species which lives well in the arid zones, where it may spend in deep dens a summer sleep (“estivation”, see Chelonia), as well as in the big rivers, not to forget the central African reed marshes.

The Saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) often attacks the man © Mazza

It does not hesitate in swimming offshore and in such a way it has reached not only the Madagascar, but even the Comoro and Seychelles Islands.

The Cocrodylus niloticus gets often close to the villages, as it is greedy of dogs, and it is the only reptilian, along with the Saltwater crocodile of Asia and of Oceania (Crocodylus porosus), which sees the man as a prey.

It seems however that this attitude is to be attributable to local habits, as in Africa the incidents do happen almost always in the same locations, whilst in the rest of the continent they tend to consider these animals dangerous only when disturbed.

The second African species, the Crocodylus cataphractus, is a predator of fishes, and may reach the 4 m of length. Typically tropical, it lives in central and western Africa. Rather shy, it is much more tied to great expanses of water than the previous one. It is often found in the coastal lagoons and comes rarely to the ground.

The last 4 species of real crocodiles live in the eastern regions.

The biggest one and more feared among these, which has also the widest diffusion area, is the Saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus).

As indicated by its common name, this animal is perfectly comfortable at sea, even more than the American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) or the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus), and this fact explains the vast distribution, from the southern tip of India to the Fiji Islands, and from the north of Australia to the Philippines.

We remind, however, that the great density populations stop close to the Solomon Islands archipelago, and that only isolated individuals have been sighted in the Vanuatu Republic (former New Hebrides, name they had when still under international, Anglo-French, rule, lasted from 1906 to 1980, date of their independency as Vanuatu Republic) as well as in the Fiji Islands.

The preferred habitat of the species is represented by the estuaries and the margins of the mangrove zones, what allows them to venture not only in the sea, but, as already written, also in the rivers with a fairly consistent water flow rate. Its diet, quite varied, includes fishes, although the extended snout is not suitable for this sort of hunting, aquatic serpents, quite numerous in these regions (see Serpentes), turtles, small crocodiles, nestlings of aquatic birds, carrions and, at times, mammals of various sizes. Even if not frequent, deadly attacks to children and even to adult humans are not and exception.

The reproduction takes always place in fresh water and it seems that, in the time standing between the two reproductive periods, the males live on the banks and undertake also long marine explorations.

The wide snout Crocodylus siamensis is on the contrary little aggressive and even tameable © G. Mazza

In the Indian peninsula, from western Pakistan to Assam, up to Sri Lanka, the Mugger crocodile (Crocodylus palustris) practically occupies the place which the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) holds in Africa, even if it is found only in fresh waters.

Also this one, however, may live in rather arid zones, with estivation done in deep dens dug along the banks of the rivers, and, in case of serious drought, it may undertake quite long terrestrial displacements, looking for permanent water streams.

But it is mainly common in the swamps, or in the wide and slow rivers. This flattened-snout animal has a varied alimentation, where the carrions occupy an important place.

In spite of the remarkable size, it is considered as little dangerous for the man, and it can be easily tamed. In the natural reserves, which surround some temples, several specimens of this race may be found living quite well in conditions of semi-captivity. It seems, however, the Sri Lanka populations, which are often considered as a particular race or subspecies of the Crocodylus palustris, are much more aggressive.

Further east, the mugger crocodile is replaced by the Siamese crocodile (Crocodylus siamensis), which is much alike, but a little smaller. It carries an absolutely similar life, apart the fact that it will never be found in the arid regions. This is found in the Indochina Peninsula, where it is never too much abundant, from Java to Borneo, whilst it seems to be absent in Malaysia and in Sumatra.

Little farther east lives the Crocodylus novae-guineae, which, as the name suggests, is endemic to Papua-New Guinea, with a subspecies, or race, the Crocodylus novae-guineae mindorensis, which lives in the Philippines.

This crocodile seldom exceeds the 2,50 m of length and lives exclusively in fresh waters, even if this has not prevented it to colonize the Sulu archipelago, at the extreme western south of the Philippines.

The long and narrow snout Crocodylus cataphractus eats fishes © Giuseppe Mazza

The Filipino race, once most abundant in several regions, is, as for most of the crocodiles, on the way of a quick rarefaction, from the eighties of the last century up to now, due to the commercial and gaming hunting to which is subjected.

The last species of the genus Crocodylus, the Crocodylus johnsoni of northern Australia, has the same type of snout, much elongated, as the species Crocodylus cataprhactus of tropical Africa, and like this last is mainly piscivorous, even if it eats what ever, also if small, comes under its teeth, from rodents to insects.

Only exceptionally it overcomes the length of 2 m and is therefore totally harmless for the man, provided, of course, that it is not disturbed, because one 1,50 m long crocodile, is still capable, if it is grasped without any precaution, to cause deep and quite serious wounds.

It is a fresh water species living in all the rivers of northern Australia, from the Fitzroy on the west, up to about the twenty-first degree of latitude south, on the south-east. Although the Saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) lives in the same regions, it never happens the two species abound in the same ecological niche.

The other two genera of the subfamily of the Crocodylines (Crocodylinae) are monospecific. The Dwarf or Bony crocodile (Osteolaemus tetraspis) of tropical Africa is represented by two subspecies or races: the Osteolaemus tetraspis tetraspis in western Africa and the Crocodylus tretaspis osborni in central Africa. The first reaches the 1,80 m of length and lives in much varied biotopes, south of the 10th degree of latitude north. The second one does not exceed the metre of length and lives more strictly in the forest.

They are small, pacific, animals, with a very short snout, equipped with ventral osteoderms (bony plates), from which comes the name of bony crocodiles.

Similar look for the Crocodylus johnsoni at home in Australia © Giuseppe Mazza

Their diet is varied and includes a remarkable proportion of aquatic invertebrates, fishes, amphibians and perhaps also fruits.

They live especially close to the isolated swamps, or by the small warm water streams, and it seems that they spend good part of their time on the ground, in shady locations.

The Tomistoma schlegelii, also known as false gavial, due to its more elongated and narrower snout than any other crocodyline, and quite similar to that of the true gavial, may be found in Malaysia as well as in Sumatra and Borneo.

It is a fairly big piscivore, totally harmless and quite rare, so much to belong to the painful “red list”, thus standing among the IUCN endangered species.

It lives only in fresh water, especially in the water stream of a certain flow rate and in the big rivers. At times, the genus Tomistoma is classified by some zoologists in a special subfamily, that of the Tomistomines (Tomistominae), but the International Commission for Zoological Nomneclature (ICZN) is still discussing about the validity of this classification.

Subfamily of the Alligatorines (Alligatorinae)

Excepting the Chinese alligator (Alligator sinensis), the alligatorines are found only in the New World and in particular in southern America. There are, however, several genera which have lived in the Old World, especially in Europe, until the mid-Tertiary, Cenozoic Era.

The alligatorines, usually smaller than the crocodylines and considered as more primitive, have all a fairly flattened and broad snout. Usually they are lazy and little dangerous animals, strictly closely tied to the fresh waters. The alligators do have the characteristic of living in subtropical and almost temperate zones, between the 25° and 35° of latitude north.

Alligator mississippiensis has a wide and flat snout with non visible fourth tooth with shut mouth © Mazza

For this reason, at least when in the most northern zone of their range, they are obliged to hibernate and spend therefore the coldest months in deep dens dug along the banks.

Once, the Alligator mississippiensis was very much common in all rivers, water streams, lakes and swamps of the south-east of USA, from Florida to Texas, reaching, west, the northern California. The intensive hunting has rarefied it so much that a legal protection by the USA Government has been necessary.

It is by sure one of the crocodiles which better tolerate the life in captivity, and in fact the zoological biologists often form breedings called “farms”, especially in Florida, in order to ensure their repopulation.

A particular morphological characteristic which allows to distinguish at first sight an alligator from a crocodile itself is that this last one, when the jaws are tightened, it has the fourth canine of the lower mandibular exposed, whilst in the alligator the same rests in a gingival pocket concealing it from view.

Like many crocodiles, its diet changes with the age. The young specimens nourish mainly of aquatic invertebrates (molluscs, crustaceans and insects). While growing up, they start paying attention to small fresh water vertebrates (fishes, amphibians, serpents at times), to which, quite soon they will add bigger preys such as rodents and aquatic birds. The big adults occasionally eat fairly great mammals, such as dogs, cervids and calves, but, as a general rule, the alligators are much less active and resourceful than the genuine crocodiles and in spite of their size, they do not ever represent a danger for the human being. But obviously, if disturbed or menaced, they do not have any difficulty in killing even an adult human.

The second member of the genus Alligator, the Alligator sinensis, lives in China, Therefore very much far away from the similar America form, but in a climatic zone of the same type: subtropical biome, with rains during the warm season. Few specimens are known, all coming from the lower basin of the Yangtze Kiang.

At home in north eastern USA is not dangerous for man if not disturbed © Giuseppe Mazza

We do not know if this species, presently rare and limited to definite zones, has had in historical times a more extended distribution, and is man is responsible for this deterioration. As there the winters are very cold, the Alligator sinensis has a very long hibernation; but, apart from this, quite little is known about this small alligator, shy and very difficult to observe in the wide flooded valley where it lives.

All other alligatorines are native to southern America and are called currently caimans, even though the zoological biologists have subdivided them in three different genera.

The most known is the Caiman crocodylus, spread from the southern part of Central America to Paraguay. There are three subspecies, or races, of it, well differentiated, which have been, for long time, considered as true and proper species. They were called Caiman yacare, Caiman crocodilus (or Caiman sclerops) and Caiman fuscus.

They are often called spectacled caimans, because, right between the eyes, they have a bony crest which somewhat reminds the central frame of the glasses.

These animals, which seldom exceed the 2 m of length, are definitely harmless. The live in the still waters: slow water streams, swamps and lakes. Their diet is in good part based on aquatic invertebrates (molluscs and crustaceans), small fishes, amphibians and small serpents.

The Caiman latirostris, living in Brazil south to the Amazon River and in Paraguay, has similar size and attitudes. On the contrary, the Paleosuchus (Paleosuchus sp. ) frequent the fast waters, at times even the rapids disseminated among the rocks. Their osteoderms (we remind that they are bony plates), extremely developed, form a sort of cuirass wrapping them completely.

This morphological character has been related to their habitat, seen the high risk of violent collisions with the rocks. This hypothesis is clearly valid, but we have also seen that the dwarf of bony crocodiles of the genus Osteolaemus, more or less protected by the ventral osteoderms, lived in quite different habitats. For this reason, the zoologists have not yet validated such hypothesis.

The Spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodylus) rarely exceeds the 2 m and has three subspecies © G. Mazza

Even though the Paleosuchus are of a rather reduced size (the biggest specimens never exceed the 1,50 m of length, as it can be seen on the list), the Smooth-fronted caiman (Paleosuchus palpebrosus) and the Dwarf caiman (Paleosuchus trigonatus) both have a diet composed mainly by vertebrates: amphibians, fishes, serpents, aquatic birds and small mammals.

The last member, the Black caiman (Melanosuchus niger), is the giant of the group. Most of the adults exceed in fact the 3 m of length and some of them reach the 4,57 m.

This caiman, widely spread in the basins of the Amazon and Orinoco Rivers, from Peru to Guianas, is the only one which, occasionally, attacks the big mammals, but, being little aggressive, there is the tendency to consider it as non dangerous for the man. But the fact remains that considering a species of crocodile or alligator little aggressive does not mean that it cannot seriously cause harm to a man, if disturbed or manipulated without the proper caution.

The subfamily of the Gavialids (Gavialinae) is represented by one only species: the Gavial (Gavialis gangeticus), diffused in southern Asia, from Indo to Irrawaddy, but is completely absent in all the south of India. It is maybe the biggest, if not the heaviest of all crocodiles and the biologists have registered specimens long even more than 7 m!

But its fundamental characteristic is formed by the extraordinarily long and narrow snout (longirostral), which, in the adult males shows a clear swelling. The gavials do preferably live in the ample water streams and in the large rivers, as well as in the estuaries and seldom come ashore. Their diet is mostly based on fishes, to which, at times, they add birds, aquatic serpents and carrions, in particular human corpses, not completely burnt, and carried regularly by the Ganges River.

It gets the name from the bony crest reminding the glasses frame © Giuseppe Mazza

It does not seem, however, that they attack big living animals, in spite of their impressive size. Therefore, they do not form a danger for the man, except what mentioned above.

Comparative Physiology of the crocodiles

In the introductions of the Chelonia, Serpentes and Sauria, we have treated about the characteristics which are common to the class of the Reptilia, in terms of systems and organs.

For instance, the Jacobson’s organ, the structure of the eye, the psychology and the central nervous and neurovegetative system, have been widely described, as well as the excretory system, comparing this last with that of the birds; furthermore, talking of the mechanisms of the “moulting” in the serpents, we have mentioned also the mechanisms which rule the renewal of the skin in the crocodiles (which, however, is not a moulting) and the aspects of the dermal appendices. The same goes for the skeletal system.

For such reason, we shall treat in the case of the order of the Crocodilia, about those structures more typical of the group, that is, the ears, as they are the only reptilians presenting a developed tympanic bulla. We shall talk about their reproductive mechanisms, and in particular about their growth rate, which has been object of study and interest by the herpetological biologists, as it has some peculiar characteristics and especially because it is characterized by much evident “allometric” increments, in times relatively short, thus involving the intermediary metabolism and relevant variations. Finally, we shall talk about their circulatory system, as, even if standing among the most primitive extant reptilians, the same is much closer to that of the mammals if compared to that of the serpents, saurians and turtles.

Cardiovascular System

Paradoxically, although the crocodiles were born just 5 million of years after the decline of the dinosaurs, having maintained intact their ancestral anatomy and physiology, they are nowadays more evolved than the other reptilians for what the circulatory system is concerned.

Circulatory system of crocodiles is more advanced than that of turtles, serpents and saurians © G. Mazza

As it is well known, the heart of the reptilians is divided only in three cavities: two atria and one ventricle.

There are, however, two aortic arches, the right and the left one; this particular anatomical characteristic is utilized as a further demonstration of the direct evolutionary descent of the class of the birds from the reptilians one (besides the cleidoic egg); as a matter of fact, in the birds the aortic arch is single and right, as vestigial residue of the reptilians structure; actually, also in the mammals, and therefore also in the Homo sapiens sapiens, the presence of a single and left aortic arch suggested to the XVIII century biologists the direct descent also of the man from the reptilians, when talking of Homo reptilis.

Obviously, this last descent is not direct, even if traces of a gradual evolution from the reptilians, passing through the birds, is evident in the mammals, not only due to the presence of the aortic arch, but also due to the limbic system (the most primitive brain structure, called “paleoencephalon”, or, also, reptilian brain) and in the case of the oldest order among the extant mammals, the Monotremes (Monotremata), for an ovoviviparous reproduction, as is the case of the Spiny anteater (Tachyglossus aculeatus) and of the Platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus).

The term Monotremes (Monotremata), is indeed a denomination given by the zoological biologists of the early XIX century, in common to the birds and reptilians, because they have a duct of reproduction and of delivery coinciding with that for the disposal of excretes (faeces, with urine, semi-solid as in the birds or liquid as in the reptilians and monotreme mammals).

The heart of the saurians, turtles and serpents is provided of two atria and one only ventricle, which two walls (emiseptae) divide in an incomplete manner. These walls limit but do not entirely prevent the mixing of the blood. The right aortic arch, from which originate the carotids, departs from the left portion of the ventricle; the left aortic arch and the pulmonary artery, which later on forks, depart for the right portion.

The heart of the crocodiles is, on the contrary, more evolved: the ventricles are two, instead of one, separated by a complete septum, like the mammals. The oxygenated blood does not mix any more in the ventricle with the blood borne of carbon dioxide (venous).

The Crocodylia are the only reptilians with ears with ample outer pinnae © Giuseppe Mazza

The circulation looks perfect (double and complete); but there are always the two aortic arches, one of which departs from the right ventricle and the other from the left one. As a consequence, the venous blood goes back in circulation through the aorta.

Furthermore, in the crocodiles, the left aortic arch where the venous blood floods is narrower than the right one; between the two arches there is a communication, the “foramen of Panizza”, which allows the oxygenated blood to partially pass from the right to the left arch. Into the systemic circulation enters mainly oxygenated blood.

And rightly as a consequence of the double imperfection of their circulatory and respiratory apparatuses, the reptilians never have a quantity of oxygen sufficient for well supplying their tissues. This metabolic factors combination leads them to be defined as “cold blooded” or, more correctly, poikilotherms or poecilotherms, or ectotherms or eurytherms (all synonyms), that is: the body temperature is variable and depends from that of the environment. Usually, it is just capable to increase of some degrees over the surrounding temperature; only a few species (such as the boa and the python) are able to increase the heat of their body during the period of the hatching of the eggs, by contracting rhythmically their coils. Such an advanced anatomic-physiologic characteristic, for the heart of one of the oldest extant reptilians, still does not find a clear and complete explanation in evolutionary terms.

Ear

The crocodiles are the only reptilians with ears equipped with ample external pinnae. These ones, usually, are fixed and do not protrude from the surface of the head. They are attached just behind the eyes and extend from each side up to the calvarium, covering the tympanium completely.

It is thought that this sort of wings protect effectively these so much sensitive organs from possible lacerations caused by submerged roots and probably also from the increase of pressure during the immersions.

At the forward extremity of each pinna, there is an operculum which is usually open when the head of the crocodile surfaces, whilst is closed during the immersion.

Also ashore the Crocodylia move quickly with the body kept higher than the saurians © Giuseppe Mazza

This orifice seems to represent the way normally followed by the sound waves, carried by the air, for reaching the tympanium.

The whole pinna has some possibility of movement, as it is articulated to the skull along its upper edge. If an animal is docile, it is possible to uplift its pinna; and with the dissection they have been able to highlight the existence of two small muscles on the rear edge which allow the animal to raise and to lower it depending on the circumstances.

In any case, in order to see a crocodile contracting its pinna, it is sufficient to spray a little water directly on the surface of the pinna. In this way, the same quickly opens and then closes several times, as it should have to expel the water, and then definitely locks.

What is however difficult to understand is why in the crocodiles there is a pinna-like structure so ample, when a simple piece of skin with a mobile folding movement should be enough for covering and discovering the auditory orifice. The structure of the middle ear and of the “Eustachian tube” is extraordinarily complicated in the crocodiles. The whole is practically surrounded by bones, in such a way that the back part of the skull appears traversed by a maze of tubes and communicating spaces, all full of air. The connexion of the middle ear and the pharynx happens through the two Eustachian tubes. Besides this connexion, the two ears communicate among themselves through the head, under the calvarium. Another extension of each cavity wedges inside the quadrate bone, getting out from its dorsal wall, for reaching a membranous tube called “Siphonium”. This penetrates the mandible through a tiny orifice of the internal face of the articular surface, ending up, finally, in the cavity of the bone. This structure is possibly drawn for the reception of the acoustic-mechanic vibrations.

Reproduction

The most prolific reptilians are probably the great sea turtles, whose deposition may reach even more than 100 eggs! But, we have to add that the Chelonia have also a particular case, that of the Pancake tortoise (Malacochersus tornieri), which lays just one unique egg at a time!

The Crocodylus porosus builds its nest with vegetables mixed with mud © Giuseppe Mazza

The females of crocodile, like also those of the great pythons, lay an abundant quantity of eggs, but it almost sure that they reproduce only once per year.

At each deposition, the number of the eggs varies between 15 and 88 in the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) and between 25 and 95 (about 60, as an average), for the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus).

Also the crocodiles, like some saurians, prepare nests close to the water. The female of the American alligator, for instance, builds up its nests with a complex technique. At the beginning, by biting and tearing up by the roots the vegetation, cleans the ground on a surface of about 2,5 m x 3 m. Then, with the help of its jaws and body, it piles up the torn plants in a compact small bridge where it creates a sort of crater with the hind legs and rotating the body.

At this stage, the hole is filled up, they say, with mud and chopped vegetables. The alligator then digs in its centre a cavity and lays there the eggs, covering them with the surrounding debris, fresh mud and aquatic plants, which it goes to find in the water and carrying them with the mouth. Finally, it flattens the nest with the body and crawls all around in such a way that the whole assumes the shape of a smooth and well formed cone, about one metre tall. The whole operation lasts about 2-3 days. The fermentation process of the vegetables increases the temperature inside the nest, allowing the normal development of the eggs, as their metabolism is kept constant.

Also other species, such as the Saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) and some caimans, for instance the Caiman larostris, build up nests of plants mixed with mud, whilst the Nile and the American crocodiles utilize a different method, by burying their eggs along the sandy banks.

The behaviour of the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus), has been precisely described by the herpetological American biologist Dr. H.B. Cott, during the second half of the sixties of the XX century.

The young alligators of Everglades National Park grow of 30 cm per year © Giuseppe Mazza

To him we owe many of the observations done on this extraordinary African reptilian, which are still absolutely valid and confirmed.

Usually, the nests are dug into the muddy and sandy ground, propped against trunks or other objects which may cast shade, at a distance of 1,80 m or even more, from the water.

Where the crocodiles are left in peace, they tend to lay the eggs together on the beach, as turtles do; but this behaviour has become rare as it is difficult, due to phenomena of human settlements and eco-tourism that the crocodiles can now live undisturbed.

Where possible, they dig the nest with the hind limbs up to 60 cm of depth, and lay there the eggs, which are covered at once.

For what the reproduction method is concerned, the crocodiles are not less careless than the turtles; but it is possible that the monitoring of these aggressive mothers is capable to markedly reduce the risks.

During the whole incubation time, the females of the American alligator or of the Nile crocodile stay on top of the net or close to the same, abstaining from eating in order to prevent intruders from approaching.

It is not given to know if also other species of crocodiles do survey their eggs in the same way, but they say that the American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) leaves the nest unprotected. It is difficult to evaluate the aggressiveness of the female which are watching the nests. It is sure that the alligators attack without any hesitation, or, at least, they frighten anyone who approaches, but these are attacks easy to avoid.

Furthermore, H.B. Cott thinks that in the case of the Crocodylus niloticus, the monitoring is always passive: most of the females observed by the scholar, while in their nest, were, in fact, in a state of torpor. It is possible that the mother’s presence by itself is sufficient to discourage the most audacious and biggest monitor lizard, as well as other predators, which hurry up in quickly plundering the nests, when the females leave them, even for short periods of time.

When the time to leave the nest comes, the young of Crocodylus niloticus emit a raucous sound for alerting the mother, which helps them stretching on the nest and rolling on itself for pushing away the sand.

In fact, it would be very difficult for the young to get out by themselves, seen that the about 30 cm thick layer which covers the eggs placed closer to the surface has hardened so much under the sun that a knife should be necessary for breaking it.

When six, they reach, with the sexual maturity, the 180 cm of length © Giuseppe Mazza

It is also possible that the mother continues the monitoring of the newborns (we remind that it is matter of apt-presocial offspring, which gets out from dirty white-white eggs with a membranous, cleidoic, with absence of cares, both homo and allo-parental) just gotten out from the nest; some reports, deemed reliable (especially by members of local tribal populations), talk about mothers worrying to accompany the brood, unharmed, up to the water, sending away storks and other types of predators.

In spite of this, a great number of young crocodiles end up eaten by birds, big fishes, lizard monitors and turtles, not to forget the adult crocodiles.

The paleontological biologist H.B. Colbert, has described, during the second half of the fifties of the XX century, the fossil nests of the horned dinosaur, Protoceratops, of the Cretaceous, Mesozoic era, discovered by this scholar in Mongolia along with the skeletons of other adult individuals.

The up to 20 cm long eggs, were placed in concentric circles, as if the female should have turned several times on itself during the deposition, forming increasingly larger circles, at the centre of a crater dug in the sand. The most important group consisted in 18 eggs, but it is quite possible that, originally, there were many more of them.

And we do not have to be surprised when looking to such sophisticated techniques of nidification in the reptilians belonging to the line of the Archosaurs (Archosauria), if we think that from other, more primitive, members of this group, possibly the Thecodonts (Thecodontia), have come, later on, the birds.

Growth rate and sexual maturity

The weight and growth increases in the various sizes of the reptilians are probably much more irregular than those of the mammals; a serpent, a lizard, a turtle or a crocodile present irregular variations in their growth, if compared to a sheep, a monkey, a lion or a human being. The zoological biologist Fitch has observed that in specimens of the pit viper, copperhead moccasin, the length, upon the birth, may vary between 160 and 264 mm and the weight between 7,1 and 14,9 g. These differences increase strongly during the first phases of the post-natal life; they depend from various environmental factors, in particular the possibility the young have to seize the preys. The American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), which, upon the birth, measures 20 cm, during the first three years of life grows up at the rhythm of 30 cm per year, thus easily reaching 135 cm.

Hunting for game or skin has exterminated the Crocodylia © Giuseppe Mazza

The growth keeps probably very quick and sustained till the ninth year of life, seen that the alligators of this age vary from the 2 to the 2,60 m, and then show a poor variability. Probably there is a window of time where the growth spurt reaches the maximum values.

These values are function of the trophic resources (ultimately, proteins are needed for growing up), the local temperature, the level of relative humidity and the quantity of day light, connected to the rhythm of the seasons, dictated by the astronomical curve done by the planet Earth; the light regulates in part the endocrine rhythms and the secretion of the somatotropin, or growth, hormone.

Basically, the environment, as well as the microclimate of the biotope, significantly affects the growth of the animal. The size of an animal, in particular the maximum dimension reached by one species, always arouses curiosity which often goes beyond the scientific interest.

For what the reptilians, and in the specific the crocodiles, are concerned, it is not easy to get data in this regard, without forgetting that it is difficult to fix a maximum limit for a species which has a theoretically continuous growth.

The only reliable figures are those coming form the collections of the natural history museums or from the zoological gardens, where the biologists have concrete material on which to operate. A stuffed individual, a skeleton or a species in captivity on which constant biometric measurements may be done, form undeniable realities, even if the specimens of great reptilians present in the zoology museums, or giant alive individuals, present in the zoological gardens, are, really, quite rare.

The great specimens of stuffed and taxidermied crocodiles which are proudly exhibited by the biologists of the British Museum of London, do not, however, exceed the 4 m of length. Moreover, it is rare that so strong and dangerous animals (and this applies also for the great Boidae) are seized or killed entire.

Often fairly valid information come from the data collected in the wild by biologists, professional hunters or rangers. The reputation of the observer is to be taken into account; if he is a zoological biologist or an herpetological biologists, the data are reliable. In the reptilians’ specific, they are reliable also if, at the moment of the observation, they do not have a metre and utilize a rope and stakes, rounding the numbers for accomplishing his measurements. The same thing may be said for the rangers of the reserves, who, for getting enrolled, must acquire at least basic scientific knowledge in biology (zoology and botany). On the contrary, this cannot be said about the hunters, as the excitement of the meeting or of the attempted killing of the animal, often induces to emphasize its dimensions, especially if the prey has run away. Furthermore, to extrapolate the length of an alligator or a crocodile from a skin obtained after having killed the animal and its skinning is quite relative as the skin has been subjected to stretching and pulling and therefore has become longer.

It happens often to get information from hunters reports (especially in Africa and South America) who say having met individuals as long as the pirogue on which they were, or so much big that the carriers accompanying them had difficulties, all together, in carrying the animal. These information are to be kept in consideration, but with the due reservations. Most of the measures reported in the scheme are obtained from seized alive specimens or from others dead in captivity; others are under assessment and confirmation. The stage of sexual maturity in a reptilian, therefore in a crocodile, alligator and gavial, may be recognized from the examination of the ovaries and the testicles, verifying if the produce eggs or mature spermatozoa.

A farm of Crocodylus siamensis in Thailand, for the leather industry © Giuseppe Mazza

Usually, the appearance of the sexual maturity in the reptilians depends more from the size than from the age, and, as we have seen, the size of the young individuals inside a same brood may greatly vary in function of several factors, especially environmental. H. B. Cott believes that the Crocodylus niloticus normally does not mate before the age of at least twenty years. The Alligator mississippiensis, one of the species with fastest growth, reaches the sexual maturity when 6 years old, when it has already reached a length of about 1,80 m.

Conclusions

The group of the crocodiles is, after me, one of the most fascinating (the reptilians in general, along with the birds, many genera of mammals, fishes and invertebrates, have been those who have induced me to become a zoologist), not only for their so much mysterious styles and customs of life, but also because it is undeniable that in their external morphology, not only the fantasy of the children, but also the adults, rightly see some tracts of those which stand between the most primitive forms of life of the vertebrates, that is the dinosaurs.

Actually, their derivation from these animals known to us only through the fossils and which have lived so much far away in the time may be observed in a sort of “crystallization” of the ancestral characters present in them.

There is no doubt that for a biologist the study of their characteristics, in a natural environment as much as possible, would help in understanding their ecology, ethology and physiology, as well as their zoogeography, which would be “fundamental”, not only in terms of evolutionary biology, but also, and mainly in practical terms, for a correct management in the nature and for a most efficient biology of the conservation.