Family : Bovidae

Text © DrSc Giuliano Russini – Biologist Zoologist

English translation by Mario Beltramini

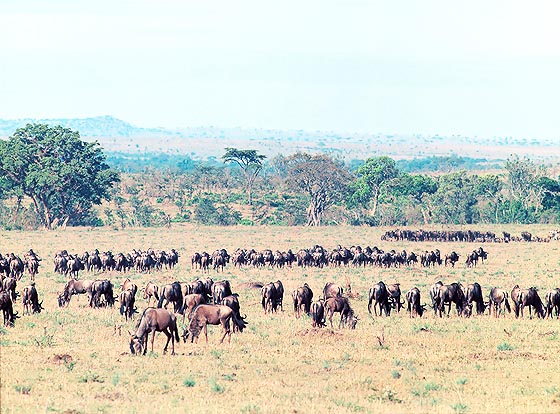

Migration of Gnus (Connochaetes taurinus) in the Serengeti © Giuseppe Mazza

The word Gnu is utilized by the biologists zoologists for indicating two species of bovids (Bovidae) : the common Gnu, also known by the name of Common wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus Burchell, 1823) and the well known black Gnu, or Black wildebeest (Connochaetes gnou), discovered and described by the German biologist, zoologist, geographer and cartographer, Eberhard August Wilhelm von Zimmermann.

Once, the last one was spread all over southern Africa, but by the middle of the nineteenth century the Boer farmers, hunting it without any scruple, brought it almost to the extinction. Only 600 specimens did survive, and now they live, protected, in the reserves of South Africa, and we shall treat of them on an appropriate fiche.

The Connochaetes taurinus, called by the Anglo-Saxons Blue wildebeest and by Africans, in Swahili, Nyumbo, was discovered by the biologist, zoologist theriologist, explorer, William John Burchell in 1823 and, later on, the classification was done by the zoo-biologist Martin Heinrich Carl Lichtenstein, who, since 1810, studied this species, endemic to central-southern Africa, classifying several subspecies. Nowadays, the biologists zoologists distinguish five of them: the Connochaetes taurinus taurinus (endemic to central-southern Africa), the Connochaetes taurinus cooksoni (endemic to the Luangwa Valley National Park, in Zambia), the Connochaetes taurinus albojubatus (Ngorongoro, Serengeti, Masai Mara: Kenya and eastern Tanzania), the Connochaetes taurinus johnstoni (southern Tanzania, Mozambique, Zimbabwe), and the Connochaetes taurinus mearnsi (Serengeti, Ngorongoro: Kenya and western Tanzania).

The savannah herbivores, even if belonging to different species, often do live in immense herds, with hundreds of thousand of heads, where do not exist phenomena of competition. It is not therefore rare to find, close to the Connochaetes taurinus, called also Brindled gnus, Blue Gnus or Blue Wildebeests, groups of Plains Zebras (Equus quagga), Grévy’s Zebras (Equus grevyi), Mountain Zebras (Equus zebra), Oribis (Ourebia oribi), Impalas (Aepyceros melampus), Lord Derby Elands (Taurotragus derbianus), Common Elands (Taurotragus oryx), Greater Kudus (Strepsiceros strepsiceros), Lesser Kudus (Strepsiceros imberbis), Klipspringers (Oreotragus oreotragus), and of many other species.

As it was rightly said by the zoo-biologist Oskar Hanriot (teacher of the ethologist Konrad Lorenz, Nobel laureate in 1973 for Biology and Medicine), such aggregations are very advantageous both for the single and for the community. As soon as an individual perceives the presence of a predator, such as Lions (Panthera leo), Leopards (Panthera pardus), Cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) and Hyenas (Hyaena hyaena), emits, in fact, typical warning screams, running away into the herd for confounding the aggressors. Furthermore, these huge communities of herbivores meet, by the ponds, species such as the Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis), the African Bush Elephant (Loxodonta africana) and the Cape buffalo (Syncerus caffer). And it is useless to add that for gazelles and gnus, big animals, such as elephants and buffalos, make a valid defence against the terrestrial predators and the African crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus), which are waiting for them by the watering place. The Connochaetes taurinus has nowadays its biggest density with 500.000-700.000 heads in the protected savannahs of the park of Serengeti, Ngorongoro, and Masai Mara (Kenya, Tanzania).

Running herd of Connochaetes taurinus © Giuseppe Mazza

In South Africa, the population density of the Connochaetes taurinus and, mainly, of the Connochaetes gnous is substantially decreasing, due to a bigger interference of the human activity towards the Kenyan and Tanzanian parks. The increasing number of farms and enclosures for the tamed livestock, takes away, in fact, areas from the pasturages, and reduces the vital space of these species. The reserve of the Waterberg National Park in South Africa is the one where is located the greatest density of population of these two species. Other subspecies are present in the remainder of the central-southern Africa, but with reduced number of specimens.

Zoogeography

The Connochaetes taurinus are endemic to the eastern, western and centre-southern sub-Saharan Africa, where they are kept in parks and natural reserves, such as the Ngorongoro, Serengeti, and Masai Mara for Kenya and Tanzania, and the Waterberg in South Africa. But some groups of other subspecies are found in the northern Botswana and in Zimbabwe. The greatest density of population is in the Serengeti, where spectacular migrations are observed, to which often associate other species of herbivores. A Complex phenomenon, which starts with the arrival of the dry season and of which we shall treat down below.

Habitat-Ecology

They prefer the biotope of the savannah, possibly close to water puddles. The Gnus in fact need to drink and to bathe at least once every two days, and stay, normally, 10-15 km far away from the puddles.

Morpho-physiology

Unguligrade, Artiodactyls, the Connochaetes taurinus have a sexual dimorphism. The male is bigger than the female, with the horns more developed, and a mane and a tuft of black, or dark brown hair, in the front part of the muzzle. Small ears, lance-shaped, frontal, small eyes. Very developed hearing and smelling senses. The males weigh an average of 250-270 kg, reach 1,40-1,50 m at the withers, the females, already said, are smaller. The horns have a crescentic look, bent upwards firstly, then outwards in the acropetal part. They are hollow, not caduceus, with circular section and wide base, smooth like the tamed bovines, and reach the span of 90-95 cm in the males, and the 40-45 cm in the females.

The coat in the sexually mature males, from the ninth week of life, assumes a blue-grey and brown-grey hue, the males are darker than the females. In the calves, first the ninth week of life, the coat is dark brown. The mane, present in the male, is formed by black or dark, stiff, hair and extends from the head, along the back up to half of the trunk. The sides and the lumbar-sacral part of the back are pale grey. It is striped (dark brown bands) along the neck and the frontal part of the body.

The tail, fringed, is formed by horsehairs.

Typical fight between males with folded forelimbs © Giuseppe Mazza

Ethology-Reproductive Biology

The Gnus (Connochaetes taurinus) are the species of herbivores more numerous of the Serengeti plains also in terms of biomass.

For this reason they are also the most frequent food for lions, hyenas, leopards and cheetahs.

During the rainy season, the herds of gnus, disperse grazing in the plains and prairies of eastern Serengeti. But this is a region crossed by few watercourses, which dry up by the beginning of the dry season.

Seen therefore the necessity of water characterizing the species, the gnus in that period tend to concentrate in herd more and more important, originating the phenomenon of beauty, rawness and dangerousness, unique in the world, which is the migration westward, towards new pasturages and watercourses.

The beginning of the migration, as the biologists zoologists have observed by the commencement of the ‘900, coincide with the beginning of annual oestrum in the females.

Like the antelopes, also the dominant males of Connochaetes taurinus fix their territories, defended against other rivalling males and where inside is present a certain number of females, with which it copulates, harem in promiscuity conditions. During the migratory stage, the possession of a territory, lasts only a few days, coinciding with the halts. As a consequence, also the families are transient. As soon as the migration of the herd resumes, the familiar nuclei dissolve: the female with the offspring will mix with the remainder of the group, whilst the males will gather acting as sentries and as soldiers.

During the whole time of the dry season, the herds remain in the western part of the Serengeti, where the gnus will find new pasturages of fresh grass and the females will deliver the babies. The deliveries increase in fact around February, coinciding with the rainy season, when there is abundance of food for the nursing females and the calves to be weaned. At times, unluckily, it happens the rainy season is late and the females are compelled to deliver in want of food, with the herd still moving, far away from the final destination. Under these circumstances, depending on the size of the herd, there can be a mortality of the progeny, miscarriages included, ranging from the 50% to the 80%.

The males reach the sexual maturity around the fourth year of life, but before the fifth they are not in condition to defend a territory and build up a harem drawing the females attention. The marking of a territory happens through the discharge of excrements and urine, but also with pheromones released by the rubbing of the pre-orbital glands and at the base of the hoofs. The olfactory marking is followed by a visual one, formed by a sequence of body movements to which a language can be associated.

The males, bigger than the females, have more developped horns, beard and mane © Giuseppe Mazza

For instance, grunting and pawing of the earth or rubbing the trunk on the ground, are prodromes of a physical fight with a dominant competitor. During the struggle, the two fighting males stand with the forward limbs bent, trying to hit each other with the horns. Usually, only the 50% of the adult males succeeds in getting its own territory and harem. A male when looking a sexual partner (but this at times happens also with the females), rubs the pre-orbital glands against the trunk of a tree, butting the same and felling it. This behaviour, together with the grunting and the pawing the earth with the horns, in addition to attract the females, is used also as warning towards possible rivals.

The females, with bicornuate uterus and syndesmochorial placenta, have a pregnancy lasting an average of 8-9 months. A few minutes after their birth, the calves are in condition to stand up, and after a few hours they toddle by their mother. They suckle for up one year, and then are weaned.

→ For general information about ARTIODACTYLA please click here.