Text © D. Sc. Giuliano Russini – Biologiste Zoologiste

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Flaming Lilioceriis lilii, disliked in gardens. Coleopterans have 330.000 known species © Giuseppe Mazza

The Coleopterans (Coleoptera) represent the most important order of insects and the man group of organisms living on the planet Earth, including about 400.000 described species.

A so high richness of species is confirmed also by the diversity of the ecological roles inside this order where are present herbivores, frugivores, granivores, fungivores, predators, parasites, symbionts, detritivores and many other alimentary specializations which have allowed the coleopterans to colonize every type of habitat in all continents (but Antarctica).

No other order of living organisms has such high number of species, which, however, increases more and more because every month the entomologists discover new species and races of coleopterans.

The oldest fossils of Coleopterans date back to the Permian period of the Palaeozoic Era, about 300 million years ago.

As for other orders of insects, still now the classification of the coleopterans is in constant reshaping, especially at level of family and of genus. The systematic classification (still under discussion) is as follows: phylum Arthropods (Arthropoda), subphylum Hexapods (Hexapoda), class Insects (Insecta), subclass Pterygotes (Pterygota), and order Coleopterans (Coleoptera). In a special systematic section, we shall treat the subdivisions relevant to the two main suborders of coleopterans, Adephages (Adephaga) and Polyphages (Polyphaga), which include about 180 families and numerous subfamilies. The most important and significant families, which will be cited as examples in the present text are the following: Carabids (Carabidae), Dytiscids (Dytiscidae), Gyrinids (Gyrinidae), Noterids (Noteridae), Hydrophilids (Hydrophilidae), Helophorids (Helophoridae), Georissids (Georissidae), Staphylinids (Staphylinidae), Cholevids (Cholevidae), Leiodids (Leiodidae), Silphids (Silphidae), Histerids (Histeridae), Lampyrids (Lampyridae), Cantharids (Cantharidae), Drillids (Drillidae), Malachiids (Malachiidae), Clerids (Cleridae), Elaterids (Elateridae), Buprestids (Buprestidae), Dryopids (Dryopidae), Heterocerids (Heteroceridae), Helodids (Helodidae), Dermestids (Dermestidae), Cucujids (Cucujidae), Nitidulids (Nitidulidae), Mycetophagids (Mycetophagidae), Erotylids (Erotylidae), Coccinellids (Coccinellidae), Endomychids (Endomychidae), Bostrichids (Bostrichidae), Cisids (Cisidae), Anobiids (Anobiidae), Ptinids (Ptinidae), Anthicids (Anthicidae), Meloids (Meloidae), Mordellids (Mordellidae), Tenebrionids (Tenebrionidae), Chrysomelids (Chrysomelidae), Cerambycids (Cerambycidae), Curculionids (Curculionidae), Scolytids (Scolytidae), Lucanids (Lucanidae), Trogids (Trogidae), Geotrupids (Geotrupidae), Scarabeids (Scarabaeidae).

The elytra, peculiar characteristic of the order: wings turned over time in solid chitinous divaricatable cases to protect the second pair of wings. Here a cockchafer (Melolontha melolontha) while taking off © Giuseppe Mazza

Finally, we have to add that alternative classifications (especially at level of family and of genus) are continuously submitted and at times approved by the International Code for Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN).

General morphological lines

The term “coleopteraa” comes from the composition of the Greek words “coleos” (sheath) and “pteron” (wing), that is, “sheathed wing”.

As a matter of fact, the most conspicuous characteristic of the coleopterans stands in the “elytra”, formed by the first couple of wings modified in two shields of more or less rigid chitin, covering the second pair of wings, protecting also the upper part of the mesothorax, of the metathorax and of the abdomen.

In the species where the second couple of wings have maintained the aptitude to the flight, therefore in most species of coleopterans, the elytra are independent: in rest position their inner margins fit together along a midline, called “suture”, whilst during the flight they are spread apart thus allowing the exit of the membranous wings.

In the scarabeids of the subfamily Cetoniinae (which include also the great African Goliathus), the elytra are merged along the suture and at the time of flight they are raised together to allow the wings to get out spreading.

They are often lively coloured, as Gaurotes virginea or Leptura cordigera belonging to the vast family of the Cerambycidae © Giuseppe Mazza

At the base of the suture, the elytra are generally separated by a small portion of the mesonotum (dorsal sclerificated lamina, of the second thoracic segment), placed on their same level, called “scutellum”, due to its usually ogival or triangular shape, similar to that of a tiny shield.

They form an often mimetic armour, like in this tiny Psyllobora vigintiduopunctata © Giuseppe Mazza

In the elytra, the ribbed structure of the original wings, has not completely disappeared and often manifests in the form of grooves or longitudinal series of dots, called striae.

The basal outer corners of the elytra are called “homeri” and often are in relief; the central portion of the same is called “elytra disk”, whilst the eventual folds formed at the sides of the body are called “epipleura”.

The membranous wings are not always apt for the flight: many coleopterans have more or less atrophied wings (brachypterous) or absent (apterous); in this case, the elytra are often merged along the suture and do not have protruding homeri whilst the scutellum can be either very reduced or absent.

In the apterous coleopterans the agility has been evolutionally sacrificed for a better protection of the body with merged elytra forming a unique casing, often very rigid; examples of such cuirass, with epipleuras which may contain the abdomen up to the sides of ventral surface, are observed in many Curculionids, such as Otiorhynchus and Tenebrionids genus like Pimelia, Erodius, etc.

The elytra are not always covering all the dorsal surface of the abdomen: they can be more or less shortened in the Staphylinids and satellite families, where however they continue in performing a protective action and, in the Meloids of the genus Meloe, where they are often reduced to stumps. In the females of some species, on the contrary, we can observe a total disappearance of the elytra and of the membranous wings, which confers the animal a larviform look; this phenomenon may be observed in several species of Lampyrids, Drilids and Scarabeids of the subfamily Pachypodinae, where the males have, conversely, elytra and membranous wings perfectly developed.

Often, like Tenebrioides mauritanicus, we still note the nervation of the old wings turned in grooves © G. Mazza

The wings of the first pair are more or less sclerificated also in other orders of insects, especially in the Hemipterans or Rhynchotans (Hemiptera from the Greek “hemi”: half, “ptera”: wing, or Rhynchota) and in the Orthopterans (Orthoptera).

In these orders the front wings are called respectively hemi-elytra and tegmina.

The conformation of the hemi-elytra in many rhynchotans confers them a look at first sight similar to that of the coleopterans. However, the rhynchotans, besides being deeply different from the coleopterans due to important biological characteristics (the first ones are heterometabolous, the second ones are holometabolous), can be easily distinguished due to the characteristic sucking pungent buccal apparatus and due to other morphological aspects.

Often, along the sides of the prothorax, it can be observed, especially in the family of the Cerambycids, acute teeth-shaped protrusions, having protective function against the predators.

Conversely, in the family of the Scarabeids, are very common relieved formations similar to horns on the upper part of the pronotum, often accompanied with cephalic horns, almost always present only in the masculine specimens, acting as characters of permanent sexual dimorphism. Much variable in the shape is also the head, especially in its terminal portion. In it we can distinguish an upper region located behind the eyes, called vertex, a space between the eyes called front, and a reduced area called “epistome” or “clypeus”, included between the front and the buccal apparatus.

But elytra can also be absent as in Firefly (Lamparys noctiluca) females, here snapped by day and by moonlight © Giuseppe Mazza

Sometimes the fore part of the head is prolonged ahead forming a rostrum (more or less curved projection bent downwards), as for many species of the very vast family of the Curculionids. On the sides of the head we distinguish also the cheeks and the temples, whilst below are present the chin and the throat: all these parts are easily identifiable for the analogy with our own ones.

Coleopterans size can be 20 cm to 0,5 mm. Here a Cryptophagidae on a strawberry petal © Giuseppe Mazza

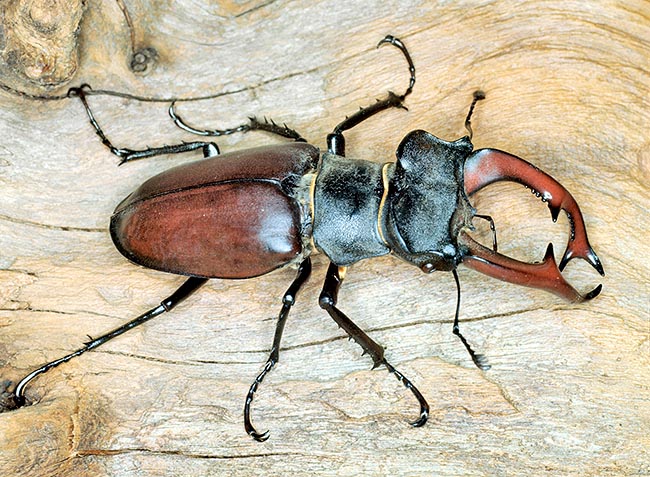

The buccal apparatus is generally masticatory and is formed by numerous parts; the most important of these are the mandibles, often equipped, on the inner edge, with robust denticles. An enormous development of the jaws can be observed in the males of many Lucanids, among which our Stag beetle (Lucanus cervus).

In this case, the mandibles do not have any more role of mastication of the food, but are used as arms in the fights between males.

Other important buccal organs are the “palps”, present in two pairs (maxillary palps and labial palps) and usually formed by three articles, rich of chemical receptors of gustative-tactile type.

Even more variable is then the shape of the antennae, organs of olfactory-tactile sense, whose morphology has often a great taxonomic importance.

They can be formed by a variable number of articles but never too many (usually, there are eleven of them).

Their shape can be uniformly elongated or moderately enlarged or thinned towards the apex. The articles at times, but the basal ones, are angularly protruding, in way to simulate a saw teeth (toothed antennae), or present elongated appendages, directed perpendicularly to the antenna itself which then is called “pectinate”, like in many Elaterids.

In genus Mordella the body prolongs like a sharp tail © Giuseppe Mazza

Quite often, the last articles of the antennae are brusquely enlarged, forming a sort of a club, and consequently the antennae are called “clavate”. In the species of the superfamily Lamellicorns (Lamellicornia), the club is formed by articles equipped with lamellar expansions, which cannot be seen in any other coleopteran, thus allowing an easy identification of the group.

In many instances, the first segment of the antenna is particularly developed whilst the following ones form a pronounced angle with it: in this case we talk of “geniculate” antennae, similar to those of the ants. This type of antennae, where the first article is called “scape”, whilst the remaining part is called “funiculus”, is observed mainly in the curculionids.

On the abdominal side of the body of the coleopterans, we can recognize the prosternum, the mesosternum and the metasternum, which form the ventral portion of the relevant thoracic segments, followed by the “sternites” representing the ventral surface of the abdominal segments.

On the sides of the thoracic segments, usually can be observed some pieces firmly articulated, called “epimeron” and “episternum”.

In the abdomen, the sternites are strongly sclerificated, whilst the tergites, that is the upper portion of the segments, are usually membranous, but the last one, called “pygidium”.

This latter is generally cuirassed because in many cases it is not covered by the elytra and protects the genital opening and the reproductive organs placed inside.

The tergites of those coleopterans that, like the Staphylinids, have reduced elytra, are very much chitinized in order to protect the abdomen. The structure of the limbs, which may have various modifications, is of great interest. The three pairs of limbs are articulated to each one of the three thoracic segments; the basal piece, called coxa, generally spheroid, articulates in a cavity, called “cotyloid” or coxal cavity, with ample possibilities of rotation in the space.

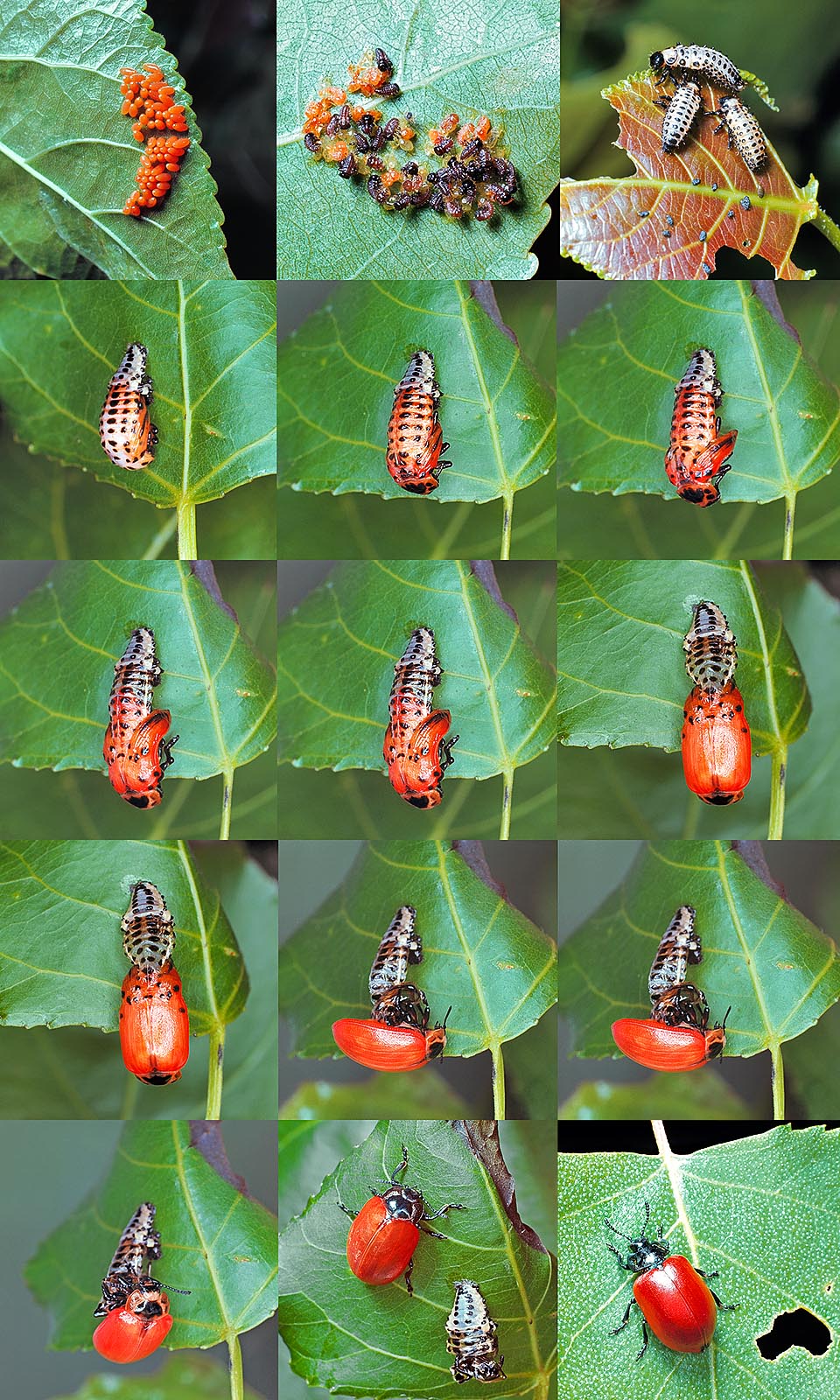

Eggs, larvae and hatching of Melasoma populi nymph. All coleopterans get through these steps, but the Meloidae family members having other stages © Giuseppe Mazza

To the coxa articulates the trochanter, usually a very small segment; in the more agile species like, for instance, the staphylinids, also the trochanters are however discretely developed. Then follow the femur, which is the most voluminous among the segments of the limb, and the tibia, more or less elongated, which may perform, in respect to the femur, angular movements of almost 180°, keeping in any case always on the same level in the space, without possibility of movements of torsion.

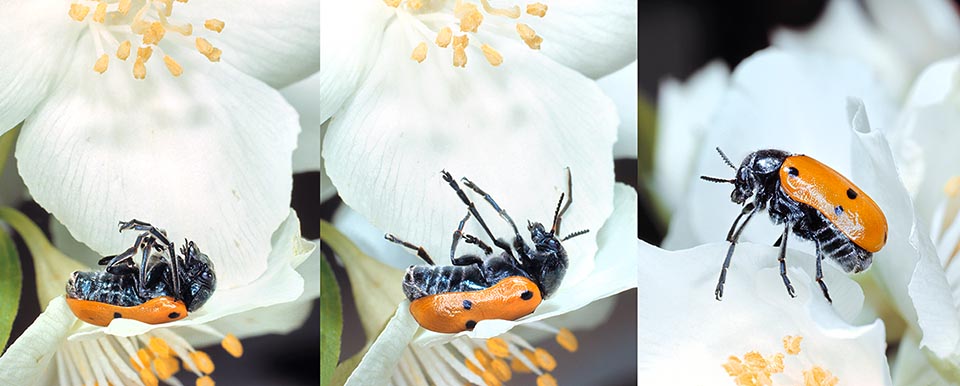

It’s Mylabris variabilis case. Its growth gets through very different look and behaviours © Giuseppe Mazza

The last segment, called tarsus, is fragmented in a variable number of articles, usually four or five. These are normally sub-cylindrical and elongated in the species running on the soil, whilst are dilated, flattened and often equipped with a felty sole in the climbing plants species.

The last tarsal article, always rather thin, is equipped at the apex by two hooks (one only at times), whilst the second to last is often divided in two lobes.

Many species use the legs for digging the ground and have for this purpose, dilated fore tibiae, toothed or in any case very robust; the legs modified for this purpose are called “fossorial”.

Even more specialized are the median legs and especially the hind ones of the aquatic coleopterans, where femurs and tibiae are shortened and strongly compressed, whilst the tarsi, also compressed, are dilated and equipped with rigid fringes of hairs, thus to function as oars and allow the swimming.

The most advanced evolution of such legs, called “swimming”, can be observed in the Gyrinids, where the median and hind legs, extremely short and dilated, allow these insects to slide with great rapidity on the water surface.

Apart elytra also the body is often armoured as in this Blaps gigas © Giuseppe Mazza

A modification of some importance can be observed in the hind legs of some Chrysomelids, Curculionids and Helodids; in these, the femurs, extraordinarily enlarged, contain powerful muscle bundles which, causing a brusque and very fast dash, allow leaps of remarkable length and rapidity.

The internal anatomy of the coleopterans is not substantially different than that of the other superior insects; the greatest differences stand in the structure of the genital apparatus, analogous to that of the other insects, but formed by differently structured elements.

The male sexual apparatus consists primarily of a great chitinized copulatory organ, called “aedeagus”, formed by a strongly developed central lobe and two lateral ones, free or merged, called “parameres”.

In the female genital apparatus the sclerified pieces are smaller and less numerous; the organs in charge of the production of the seminal cells, called “ovarioles”, are membranous and convey their product in a small container usually sclerified, called “spermatheca”, having the function of conserving the sperm up to the complete eggs ripening. The dimensions of the coleopterans are much variable: the smallest species do not even reach half a millimetre in length, whilst the biggest ones, may reach some fifteen centimetres.

The well articulated legs adapt to various life styles. In Oedemera nobilis the males, with huge femors, show an unusual sexual dimorphism © Giuseppe Mazza

One of the biggest coleopterans, the Hercules beetle (Dynastes hercules), may exceed the twenty centimetres, but part of these belong to the very long horns of the head and of the prothorax; this coleopteran is an inhabitant of Central and South American tropical forests from the sea level up to about 1200 m of altitude.

In some species, like Lucanus cervus, the jaws become horns for males fights © Giuseppe Mazza

Another example is the Titan beetle (Titanus giganteus), a Cerambycid famous for its about 17 cm, with a geographic distribution in the New World, specifically in South America, that is in Brazil, Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, etc. The most striking characteristic of this coleopteran, besides the size, is that the male, when about to fight with a congener or if in presence of a situation of danger emits a warning and intimidatory hiss.

Biologic cycle, ecology and geographic distribution

As mentioned before, the coleopterans, being holometabolic insects, undergo during their pre-imago development two well distinct phases: the larval phase, where the insect carries on an active life, and the nymphal phase, shorter, spent in immobility. During the larval phase, the insect is subject to moults, after which the body dimensions increase, whilst the general appearance of the body keeps more or less unchanged. The larvae of the coleopterans vary a lot in shape and in liveries, depending on the groups: in the phytophagous species (nourishing of plants) we see larvae with soft body and at times without legs apt for the locomotion (for instance, in the Curculionids the larvae are apodal); conversely, in many carnivorous species, the larvae are more or less armoured, agile and aggressive towards potential preys.

For the same aim, as in Oryctes nasicornis, teeth and bulges get out in the prothorax © Giuseppe Mazza

The larvae of the Adephages are particularly aggressive: for instance, the larvae of the Carabids, are terrestrial, often coexist with the adults and are predators like these ones. Even more voracious are the larvae of the big Dytiscids, which carry on an aquatic life like the adults and wreak havoc of tadpoles, annelids and small fishes.

In all Adephages the larval look is completely different than that of the adults: the larvae of the genus Carabus have widened protective tergites which render them similar to woodlice, crustaceans of the order of the Isopods (Isopoda), the so-called Pill-bugs or Pill woodlice; on the contrary, the aquatic larvae of the genus Dytiscus are thin and elongated, with the head well separated from the body and long mandibles. In the larvae of the phytophagous coleopterans, we may note conspicuous differences, depending if these live on the aerial areas of the plants, or underground nourishing as fossorial species of roots, therefore called “rhizophagous”, or of wood, called then “xylophagous”.

The larvae living on the plants on the plants have legs capable to adhere to the leaves or to the stems, and can be cryptic or adorned with rather garish colours; on the contrary, the fossorial or xylophagous ones usually depigmented. In the xylophagous species, the larvae are often apodal or have very reduced legs: this is observed in general in the Cerambycids and in the Buprestids, whose larvae seem big segmented white and mushy worms, equipped with robust dark mandibles.

There can be also a huge rostrum at the head apex, as in Antliarhinus zamiae © Giuseppe Mazza

Typical are the larvae of the Lamellicorns, who have more or less developed legs but little efficient seen the eight and the shape of the body, ventrally curved to form a “C”. They usually live deep set in decaying wood, in the droppings or in the soil among vegetal debris and roots.

Completely different from the larvae of the other coleopterans are finally those of the Meloids, like the so-called Spanish fly (Lytta vesicatoria), which carry on a parasital life in the nests of the Hymenopterans (Hymenoptera) melliferous or predator.

As a matter of fact, the larvae of these coleopterans besides having very weird forms undergo moults which alter deeply their structure and sometimes encounter periods of immobility similar to those typical of the nymph, also during the larval status.

Shortly before the metamorphosis the coleopterans mature larvae dig a small cell into the ground or, for the xylophagous species, into the wood, where they rapidly turn in pupae (nymphal phase). These then will wait for the final phase of the metamorphosis in the most absolute immobility, keeping the legs, the antennas and the head folded on the ventral surface.

Many Scarabeids, among which the chafers (Cetonia) and the May bugs (Melolontha) build up also solid involucre, formed by loam and fine wood debris kneaded with saliva. These involucres are much similar to those utilized by the chrysalides of many Lepidopterans.

The coleopterans frequent the most varied habitats and present various diets. The highest number of species lives parasitizing the plants, often specializing so much to limit the choice to only one plant as host.

The most specialized phytophagous species stand in the families of the Chrysomelids, Buprestids, Cerambycids, Curculonids and Nitidulids. Depending on the families and the genera, the phytophagous may nourish of leaves (phyllophagous), of flowers (anthophagous), of fruits (carpophagous), of seeds (spermophagous), of lymph (lymphophagous), of roots (rhizophagous) or of wood (xylophagous). As example of phyllophagous species we mention the chrysomela of the poplar which carries on its reproductive cycle on the trees of the genus Populus (family Salicaceae).

Ocypus olens is a 25-28 mm night carnivore, with elytra reduced to stumps. Menaced, opens the jaws and

raises the tail like a scorpion emitting itching liquid and unpleasant warning gases © Giuseppe Mazza

In the category of the xylophagous stand most of the Cerambycids and of the Buprestids.

As an example, we mention the big Great Capricorn beetle (Cerambyx cerdo), which, when larva, nourishes of the host plant wood, whilst, when adult, usually sucks the lymph that is getting out from the fissures of its bark.

Numerous other coleopterans live under the barks: they essentially belong to the Scolytids, such as Dryocoetes autographus and Dendrophagus crenatus, to the Cucujids like the lovely Cucujus cinnaberinus (protected by the Habitats Directive), to the Bostrichids, like the Bostrichus capucinus which develops mainly in the oaks.

Most of the predators act on the soil, where is a greater number of potential preys amongst the small invertebrates (not only insects, but also earthworms, isopod crustaceans, snails, etc.) which form the edaphic fauna.

A great number of predatory coleopterans belong to the Adephages: terrestrial predators par excellence are in fact the Carabids, who, during the night, perform their hunting rallies, whilst during the day keep hidden under the stones or among the roots of the plants; on the contrary, the Dytiscids and the Gyrinids have perfectly adapted to the aquatic life and are mostly diurnal.

Titanus giganteus, which may exceed 16 cm, jaws can easily break a pencil © Gianfranco Colombo

Conversely, always in water do live also phytophagous coleopterans: they are mainly Hydrophilids, to which is afferent Hydrophilus piceus, one of the largest coleopterans of our country.

Other families more or less related to the aquatic or riparian habitats are the Dryopids (aquatic adults, riparian fossorial larvae), the Heterocerids and the Georissids (both riparian when adult as well as when larvae). An extremely high number of species shows much more unusual habits, nourishing of fungi (mycetophagous), of excrements (coprophagous), of decaying vegetable organic matter (phytosaprophagous) or of dead animals (zoosaprophagous or necrophagous).

The first ones belong to a vast and heterogeneous range of families, finding numerous members among the Staphylinids, the Mycetophagids, the Erotylids, the Endomychids and the Cisids.

Among the Erotylids we recall very much showy species in shape and in colours, like Cypherotylus dromedarius (Iquitos, Perù) and Ischyrus quadripunctatus (USA). The coprophagous live associated with the excrements, especially those of herbivorous animals, of which they feed and in which they lay the eggs.

The antennae, manifold after the function, usually have 11 articles, as Evodinus interrogationis © Giuseppe Mazza

They include representatives especially among the Lamellicorns, with thousands of species belonging to the families Scarabeids (Scarabaeus, Copris, Onthophagus, Aphodius, ecc.) and Geotrupids.

The species of the genus Scarabaeus make small balls of dung forming a sphere which they carry walking and by rolling it up to a point they deem suitable for digging.

After having interred it, these insects use their spherical reserve of food for nourishing but also for building there an underground nest where to breed their own larvae. However, most of the other coprophagous scarabeids dig tunnels in the ground directly under the dung, filling them up of alimentary provisions for the larvae. In this way, exposing less, they reduce the predation of birds and other animals. Finally, the smallest scarabeids (Aphodius) and many coprophagous Hydrophilids (Cercyon, Sphaeridium) lay the eggs directly into the stercorous mass.

The saprophagous include an enormous number of species: it is sufficient to think to the family of the Tenebrionids which, alone, includes at least 20.000 species, most of which nourish of decaying organic substance.

Not rarely adults and larvae have different look, as Cryptoleamus montrouzieri used for biologic war against mealybugs © Giuseppe Mazza

The communities zoosaprophagous coleopterans, called also necrophagous, are less numerous than those of the phytosaprophagous ones: the richest taxonomical components are formed by Silphids, Cholevids (former Catopids), Histerids, Nitidulids, Staphylinids and Trogids.

Also those of Tenebrio molitor, bred to feed birds and reptiles, are very different from the imagines © G. Mazza

Among the Silphids, particularly important are the necrophores (Nicrophorus) who, working in team, are even capable to inter the corpses of the small mammals, where they do lay their eggs.

The Trogids are a particular case because they nourish mainly of keratin, substance present in the hairs, the nails or the feathers of the dead animals.

They are the last to attend the banquet as they love the corpses in advanced state of decay, more or less dried up by the sun on the arid pastures or in the savannahs. To them associate some species of Nitidulids and of Dermestids. Particular attentions deserve the parasitic species of social Hymenopterans, like the ants. Firstly, we have to remind the Paussini, a very interesting tribe of Carabids, parasites of the ants, and the Clavigerins, tribe belonging to the Staphylinids of the subfamily Pselaphinae.

Both these groups, even if not being related to one another, have particularly enlarged and wide antennae. As a matter of fact, the Clavigerins get their name form the old Greek (= carrier of club), in reference to the enormous development of the modified antennae. All these parasites of the ants are called myrmecophiles and once were considered symbiont to the same, as, in exchange of the hospitality and the food, they offer them a particularly appreciated substance, indeed intoxicating, which, however, may cause social disorder.

Mimicry is the winning card of many predators like this Cicindela campestris © Giuseppe Mazza

For instance, the Staphylinids such as the Lomechusa strumosa and the Lomechusa atemeles, entering an anthill of the genera Formica and Myrmica, expose the anal trichomes (modified hairs) to the ants approaching them, secreting a liquid rendering them totally dependant from the coleopteran. Consequently, these doped individuals stop working for their society, devoted only to the care of the intruder, whilst the larvae of the ants are abandoned to their destiny, and, being unable to feed autonomously, they die.

Analogous phenomena of exploitation of the anthill are observed in the aforementioned Paussini (which actually nourish of the larvae and the eggs of the hosting ants) and in the Clavigerins.

Some coleopterans, instead, live in the dens of rodent and insectivorous mammals, always in more or less strict relations of parasitism with the occupants. Among these coleopterans the most odd and specialized is the very small Platypsyllus castoris, North-American species of the family of the Leiodids which, as the name suggests, lives in the dens of the beavers. The coleopterans entrust their defence mainly on the resistance of their armour, but often use other measures: so, some of them, if disturbed, emit caustic liquids or gases, as is the case of the Carabids of the genus Brachinus and the Staphylinids of the genus Paederus.

Coleopterans stupid? No! When Lachnaea sexpunctata feels danger falls down feigning dead. Then revives and takes off © Giuseppe Mazza

The first ones are commonly called “bombers” due to the crackling produced during the emission of a gas getting out from their anus and may cause a burning feeling on the human skin. The Paederus, on the contrary, emit a liquid which may cause a more or less, even if temporary, dermatitis.

Who said they don’t care progeny? Attelabus nitens female cuts and rolls up leaves like cigars to protect the eggs. This odd nest falls down after 6 weeks and larvae hibernating inside become nymphs in spring © Giuseppe Mazza

Lots of coleopterans use the cryptic mimicry, like some green species of Chrysomelids of the genus Cassida, very difficult to distinguish on the leaves, and various Cerambycids, for instance those of the genera Acanthocinus and Mesosa that are camouflaging with the bark of the trees.

Others, instead, defend through the Batesian mimicry, scilicet, in becoming conspicuous in order to be mistaken with insects protected by venoms, repellent tastes or by stings.

Various cerambycids imitate in the drawing some species of wasps or of meloids, thus maintaining at a distance the possible predators who have learnt to avoid the stings of the hymenopters or the venoms of the imitated coleopterans.

Another defensive system widely used is the “thanatosis”: the insect, feeling menaced, withdraws its legs and falls on the ground, feigning death and thus being confused with seeds, fragments of wood or pebbles: this is the case of many Curculionids, Sacarabeids, Tenebrionids, etc.

The great majority of the predating, parasitic, coprophagous and necrophagous coleopterans are very useful for the agriculture and the sheep-farming.

The predators and the parasites control the number of the phytophagous invertebrates (from the terrible mealybugs to the snails) which, otherwise, would destroy the vegetation of the pastures and the cultivated produces.

Just to give an example, the family of the Coccinellids includes numerous predating species of Rhyncotans (aphids and mealybugs), when adults as well as when larvae: Rodolia cardinalis is a monophagous ladybug, specific predator of the cottony cushion scale (Icerya purchasi), dangerous for the citrus; Coccinella septempunctata, on the contrary, is a generic predator of Aphids, also very dangerous for various cultivated plants, including the roses of the gardens. The coprophagous coleopterans (especially Scarabeids) and necrophagous (mainly Silphids) have the important role of freeing the surface of the ground from the excrements of the herbivores and from the corpses of the animals.

To feed larvae, Geotrupes stercorarius buries the eggs, digging, big balls of dung © Giuseppe Mazza

Instead, many species of phytophagous coleopterans can have a serious impact on the cultivations, especially where the number of insectivorous vertebrates (mainly birds and amphibians) has decreased due to the hunting activity or the land reclamations.

Among the most harmful coleopterans stand many Curculionids, Chrysomelids, Cerambycids and sometimes Scarabeids (May bugs).

Very famous is the Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata), a chrysomelid which may reproduce in mass and cause very serious damages to the cultivated Nightshades, especially potatoes and eggplants.

Native to North America, this species has been accidentally introduced in Europe by the end of the XIX century, reaching then Italy during the forties of the last century.

Among the curculionids the most infamous is instead the Granary weevil or Wheat weevil (Sitophilus granarius), which attacks mostly the seeds of cereals conserved in the barns; although each individual does not usually damage more than one single seed, these small animals reproduce quickly and destroy thousands of tons of wheat every year.

The most feared Italian scarabeid, at least till the last century, was the Maybug (Melolontha melolontha), nowadays in sharp decline, which is often subject to periodical demographic explosions and has been a real pest for the horticultural cultivations.

Often larval diet differs from adults’ one. The splendid Cetonia aurata when young eats roots, when adult flowers © Giuseppe Mazza

The larvae nourish of roots whilst the adults eat the leaves. In the past, this scarabeid has caused enormous damages and even serious famines; by historical reports it is related that in the seventeenth century some Irish populations, in order not to succumb to the famine, were obliged to feed of the Maybugs which had caused the same.

Most coleopterans like Galerucella luteola eat vegetables. Others are carnivorous © Giuseppe Mazza

Many coleopterans, Cerambycids and Buprestids, can cause remarkable damages to the timber, due to the long tunnels dug by their xylophagous larvae, whilst the Ptinids and the Dermestids cause often damages to the hides and to the preserved foodstuffs.

Among the most singular damages caused by an insect we have to remind that produced once by some Bostrichids gnawing cables lead.

As said in the beginning, the coleopterans are diffused all over the world, even in the most inhospitable environments: a great number of them are found also in the deserts, where they are mainly represented by Tenebrionids, and even high in the mountains where they usually push up to the limit of the perennial snow.

Systematic insights

As mentioned at the beginning, the order of the Coleopterans is subdivided in 2 suborders: Adephages (Adephaga) and Polyphages (Polyphaga). Most of the Adephages belong to only three families: Carabids, Dytiscids and Gyrinids, whilst the Polyphages present a much more complex and discussed diversification, where several subfamilies have been proposed.

Oxyporus rufus eats fungi, others hides or corpses © Giuseppe Mazza

The simplest (even if not agreed by modern authors) consists in 7 subfamilies: Palpicorns or Hydrophilids (Hydrophiloidea), Staphylinids (Staphylinoidea), Diversicorns or Malacodermoids (Diversicornia or Malacodermoidea), Heteromerans or Tenebrionods (Heteromera or Tenebrionoidea), Chrysomeloids (Chrysomeloidea), Lamellicorns or Scarabeoids (Scarabaeoidea), Curculionoids (Curculionoidea).

The Caraboids, only members of the Adephages suborder, mainly include terrestrial predator species (as is the case of the Carabids) or aquatic (Girinids and Ditiscids).

The amplest family of the group is that of the Carabids, whose members are spread all over the world with about 25.000 species; they are usually characterized by slender forms, long legs and sharp mandibles.

Among the numerous genera we remind three of them, quite well known for their big size: Carabus, Cychrus and Calosoma.

The genus Carabus includes numerous big species, suitable for predating a vast number of terricolous invertebrates, like Carabus olympiae, endemic to Sessera Valley, in Piedmont, and Carabus famini, endemic to Sicily and North Africa. The species of the genus Cychrus are characterized by the very thin prothorax for better penetrating inside the shells of the snails (i.e.: Cychrus angustatus, Alpine species; Cychrus angustitarsalis, endemic to China, Sichuan province).

Finally, the genus Calosoma, has often arboricolous species which nourish of lepidopterans’ larvae.

A very famous species, protected by the Habitats Directive, is Calosoma sycophanta, utilized in France in the biological struggle against the stinging caterpillars of various moths dangerous to poplars and oaks, among which the harmful pine processionares and the lymantrias. Other two very peculiar genera are: Scarites with big fossorial species living on the sandy soils and the coastal dunes nourishing mainly of snails (i.e.: Scarites buparius, present in the Mediterranean countries); Bembidion, with numerous species living in the substratum of riparian habitats.

Cerambyx cerdo larvae eat wood, adults suck the sap from trunks fissures © Giuseppe Mazza

Among the most diffused or riches of species genera we remind als Pterostichus, Harpalus, Amara and Brachinus.

The Dytiscids, exclusively aquatic as already said, are characterized by a hydrodynamic silhouette and swimming legs strongly flattened that are used as oars. In our territory, are present some big-sized species such as Dytiscus latissimus, Dytiscus marginalis and Cybister lateralimarginalis, present in various European countries, Italy included.

Moreover, the Dytiscids present also medium and small-sized species, as is the case of the genera Hydaticus, Gaurodytes, Hydroporus, Laccophilus and Noterus (this last one is nowadays considered as a family in its own, the Noterids).

Similar to the Dytiscids are the Gyrinids, which distinguish thanks to their capacity of skating on the water surface, where they nourish of insects (mainly Dipterans) which fall in the water during the swarming.

Inside the Polyphages, one of the most numerous superfamilies is that of the Staphylinoids, rather heterogeneous, where the most known families are the Staphylinids (that nowadays include also the Pselaphids), the Silphids, the Cholevids (former Catopids) and the Histerids. The Staphylinids form (along with the Curculionids) the family of coleopterans most amply represented in the Italian fauna, and also at the European level. Their body is usually thin and elongated, characterized by much shortened elytra in most of the species.

Problems for man start when, like Sitophilus granarius, they attack foodstuffs © Giuseppe Mazza

Among the numerous genera we cite: Oxytelus, Stenus, Xantholinus, Staphylinus, Ocypus, Philonthus, Quedius, Aleochara, Atheta, Sipalia.

The Pselaphinae are a subfamily of Staphylinids, once considered as a family itself. Inside them we find the tribe of the Clavigerins, already mentioned due to their peculiar adaptations allowing these very small coleopterans to live together with the ants.

Very characteristic are also the Histerids, equipped with extraordinarily solid armour and robust fossorial legs.

Though predators, they must, in their turn, protect from the attacks of other animals, and therefore they protect themselves by means of the thanatosis, by adhering very closely to the body both head and legs, in way to reduce the risk of amputations.

The best known genera are: Hister, often found in the excrements where predate the coprophagous Scarabeids; Saprinus, often found in the corpses; Hololepta, having very flattened body for living under the barks of the trees. The Palpicorns or Hydrophiloides, so called because its members have very long palps, include one family only, the Hydrophilids, with aquatic species of big size, such as Hydrophilus piceus, widely diffused in Europe, where is the biggest aquatic coleopteran.

Female with eggs, larvae and nymphs of Potato bug (Leptinotarsa decemlineata) real plague for potato cultivations © Giuseppe Mazza

To the Hydrophilids belong also species adapted to live in the excrements, especially into the very fresh or semi-liquid ones, as is the case of the genera Cercyon and Sphaeridium.

Damages done by Scolytidae larvae. Left, the tunnel where eggs were laid © Giuseppe Mazza

The genus Helophorus, after many authors as an independent family (Helophorids) includes very small species (even 2 mm) where the adults are semi-aquatic and nourish of algae or decaying vegetables whilst the larvae are predators and live in the humid soils.

The Diversicorns or Malacodermoids (Malacodermoidea), which include by them only more than a half of the families of coleopterans, are extremely heterogeneous, so much that in the most modern classifications, they have been subdivided in independent superfamilies (Cantharoidea, Buprestoidea, Bostrichoidea, Elateroidea, Cucujoidea, etc.).

The most known families of the diversicorns are the Lampirids, to which belong the fireflies, the Cantharids, the Malachiids, the Clerids, the Buprestids, the Elaterids, the Dryopids, the Nitidulids, the Coccinellids, the Endomychids, the Bostrichids, the Anobiids, to which belongs part of the woodworms of the furniture, and the Ptinids. Almost as heterogeneous are the Heteromerans or Tenebrionoids (Heteromera or Tenebrionoidea).

Among the most important families of the heteromerans, stand the Meloids, the Mordellids, the Anthicids and the Tenebrionids. The meloids, that present a particular and anomalous larval development, include some among the strangest coleopterans, like the big Meloe characterized by very short elytra if compared to the enormous turgid abdomen (i.e.: Meloe violaceus). In the meloids we talk of “hypermetamorphic” development, where in addition to the normal status of larva, nymph (pupa) and adult (imago), appear other stages, with huge differences at morphological level and in the habits of life.

Also home furniture is attacked by woodworms. On top, spawning female of genus Lyctus with nymph and traces left by an adult birth. Below woodworm of genus Anobium with larva and close up of wood now totally destroyed by insatiable hunger of these tricky home coleopterans © Giuseppe Mazza

Odd are also the Mordellids, endowed of a highly compressed body on the sides and of an often prolonged pygidium, shaped like appointed tail (i.e.: Tomoxia lineella), and the Anthicids, which recall the ants in their shape (i.e.: Acanthinus albicinctus).

Adults help pollination, but Trichoides apiarius larvae destroy honeycombs in hives © Giuseppe Mazza

The Tenebrionids form the amplest family of the group, and are diffused mainly in the warm and arid countries, being the most important inhabitants of the desertic and sandy zones. However, they include also species suitable to live in the human foodstuffs or in the humid cellars, like the mealworm beetle (Tenebrio molitor) and other genera (Tribolium, Blaps).

Others live in the dead wood of the old trees and carry on a role of biodegradators in the forest eco-systems (Helops, Stenomax, Accanthopus, Colpotus, etc.).

More uniform, but very rich in species, are the Chrysomeloids, to which belong the two big families of the Chrysomelids and of the Cerambycids. The first ones, spread all over the world with about 30.000 species, are often adorned with lively metallic colours and live mainly on the plants where they eat the leaves at the adult stage as well as at the larval; the second ones, conversely, do stand out due to the slender body and the very long antennae.

The larvae nourish of the wood of the trees; some species are protected by the Habitats Directive (Cerambyx cerdo, Morimus funereus, Rosalia alpina). To the Curculionoidei, so called because of the presence of a rostrum at the apex of the head, belongs the largest family of the entire Animal Kingdom, that of the Curculionids, with 40.000 species.

Phyllobius argentatus. With 40.000 species Curculionidae family is the widest in Animal Kingdom © G. Mazza

Even if, after many authors, the Curculionids (sensu lato) should be divided in different families, those attributable to the Curculionids (sensu stricto), should be in any case a very high number in respect to the others.

They are abundant also in Italy, with little less than 2.000 species; the most important Italian genera are: Apion, Larinus, Liparus, Otiorhynchus, Phyllobius, Polydrusus, Lixus, Acalles, Ceutorhynchus, Curculio, Tychius and Rhynchites. We remind also the genus Rhynchophorus, that includes very big, lively coloured from the red to the orange, species called in the complex red palm weevils.

Native to the tropical countries, these species have extended their range taking advantage from the human means of transportation of the palms for commercial purposes. The palms planted in the Mediterranean countries are nowadays highly endangered by the invasion of Rhynchophorus ferrugineus, native to southern Asia where initially lived on the coconut palms.

To the Curculionidae (sensu lato) belongs also another important family, the Scolytids. These include numerous xylophagous small species, equipped with a little developed rostrum, which nourish of the cambium under the barks of the trees, causing considerable damage to the forest economy.

Rhagonycha fulva is a Cantharidae common in our gardens © Giuseppe Mazza

Some of them have specialized to live on certain species of trees, like Scolytus multistriatus species linked to the elms (Ulmus) and Tomicus piniperda which damages the pines (Pinus).

Finally, the Lamellicorns or Scarabeoides are so called because of the antennal club forged in lamellae. They include various families among which the most important are: Scarabaeidae, Geotrupidae, Trogidae and Lucanidae.

The vastest and most important family of this group is that of the Scarabeids, including about 20.000 species, diffused in the entire world.

An important ecological group of the scarabeids is formed by the coprophagous (stercorary) species, whilst the phytophagous (floricolous or terricolous) ones usually live on the plants when adult and in the soil or in the dead wood when in larval status.

Very spectacular and interesting are the giant species of the genera Goliathus, Dynastes and Megasoma, among which stand the bulkiest species of the extant coleopterans.

The Goliath beetle (Goliathus goliatus) lives in the forests of central and western Africa and belongs to the subfamily Cetoniinae, like the common Cetonia aurata diffused in the European gardens.

To this subfamily belong many species very striking due their magnificent colourations with metallic and iridescent reflections, diffused mainly in the tropical forests. Conversely, the species of the other two genera are unique to central-southern America, from Mexico to Amazonia.

The males of the Hercules beetle (Dynastes hercules) have two much developed horns, one on the head and the other on the thorax, used by them as if they were forming a gripper for holding each other and fighting. Giant species exist also among the coprophagous, like the African ones of the genera Heliocopris and Pachylomera, which prefer the excrements of elephants and rhinos.

Oxythyrea funesta doesn’t eat pollen only, but destroys many flowers buds © Giuseppe Mazza

In Europe, the biggest species belong to the genus Scarabaeus, for instance Scarabaeus sacer and Scarabaeus typhon, nowadays in steep decline, but most of species are much smaller and belong to the genera Aphodius and Onthophagus.

Among the phytophagous, we remind the Melolontha, with the cockchafer, Oryctes, with the European rhinoceros beetle (Oryctes nasicornis) and Cetonia, with the Rose chafe (Cetonia aurata).

To the family of the Lucanids belongs the Stag beetle (Lucanus cervus), characterized by a strong and spectacular sexual dimorphism, as the male has enormously developed mandibles which are usually mistaken as horns, analogous to those of the cervids (hence the common names in several languages).

It is one of the biggest European coleopterans, and is still fairly common in the Italian deciduous woods.

Finally, the Trogids include modest looking species which consume keratinous substances (feathers, hairs, dry skin) in the corpses of the animals.

The coleopterans in our gardens, in the cultivated fields and in the school

Also the Trichius, of the same family of Scarabaeidae, doesn’t spare gardens © Giuseppe Mazza

As we have seen in this shirt treatise about the coleopterans, to this order belong some among the most curious and lively coloured insects, even within the Italian fauna.

These nice insects populate also our parks and gardens, therefore are easily observable, and can be utilized for the environmental education of the children or, generally, of the public, under the guidance of the teachers of the secondary schools or of experienced personnel of associations furnishing auxiliary services to the teaching.

In fact, the coleopterans can be found practically everywhere, and, but few well known exceptions, are completely harmless and do not transmit diseases to the man.

Moreover, they allow assisting in short time to extraordinary and of great effect phenomena such as the metamorphosis.

In Italy they estimate that there are about 12.000 species of coleopterans: many species may be observed during a walk in the wood, in the country and/or in the mountains. However, we see quite frequently these nice small animals even remaining in the city, while walking in a public garden, or staying comfortable in our garden.

Buprestidae, here Acmaeoderella flavofasciata, are lithophagous. Larvae dig tunnels also in leaves © G. Mazza

For instance, when observing the insects living on the flowers in spring, it is very easy to sight a cantharid like the Rhagonycha fulva, predator of small invertebrates, a green emerald scarabeid like Cetonia aurata, or small coloured cerambycids of genera Stenopterus, Clytus, Leptura or Chlorophorus, busy in nourishing of pollen and nectar.

Furthermore, it is sufficient to lift a stone or some abandoned brick in a garden for finding various species of Carabids, Tenebrionids and Staphylinids.

All these small animals can be easily maintained in life in transparent containers trying to recreate their habitat and to discover what they nourish of.

It must be kept in mind that, like all animals, the coleopterans tend to prefer the uncultivated zones instead of the cultivated ones, but are fairly abundant in the pastured ones, where the presence of the herbivores rouses a dynamic process if fertilization and of renewal of the herbaceous vegetation.

The diet of these insects, as briefly said before, is extraordinarily varied. Practically, a resource which cannot be appreciated by some species does not exist.

Otiorhynchus sulcatus, a night curculionid, eats leaves, whilst larvae attack roots © Giuseppe Mazza

Many species of coleopterans are phytophagous and therefore may cause serious damages to the intensive agriculture, in artificial systems where there are no predators and parasites of the insects.

Many phytophagous species (especially Chrysomelids and Cerambycids) have been introduced in Europe together with the cultivated plants native to other continents, mainly of the New World, and can cause enormous damages to these fruit and vegetable products. However, we have seen that other coleopterans are predators, whereby the gardeners and the farmers should look favourably at them, since they nourish of harmful parasites to the cultivations and to the plants.

For example, the larvae of the big carabids (Carabus and Cychrus), eat greedily a huge quantity of snails and slugs (snails without shell).

Also the larvae and the adults of many ladybugs are ferocious predators of insects harmful to the cultivated plants, in particular of aphids and mealybugs. For this reason, it should be possible to reduce the polluting load of the insecticides used in agriculture, protecting these natural predators n the cultivation and, if necessary, to resort to the introduction of some exotic species able to control the harmful insects native to other countries.

All bad? No! Some are good for gardens, as Carabus violaceus who attacks snails and slugs, or the ladybugs who eagerly devour aphids when larvae and also when adults. Left, banquet of tropical ladybugs, right a Coccinella septempunctata eating its prey © Giuseppe Mazza

Through these forms of biological struggle and going back to models of extensive agriculture, instead of the intensive one, it might be possible to better the quality of the habitat and of our life.