The secrets of the forest. Animals and plants of the Australian rain forest. Palms, ferns, lianes, homaruses out of water, marsupials, flying foxes, parrots and birds that don’t brood.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

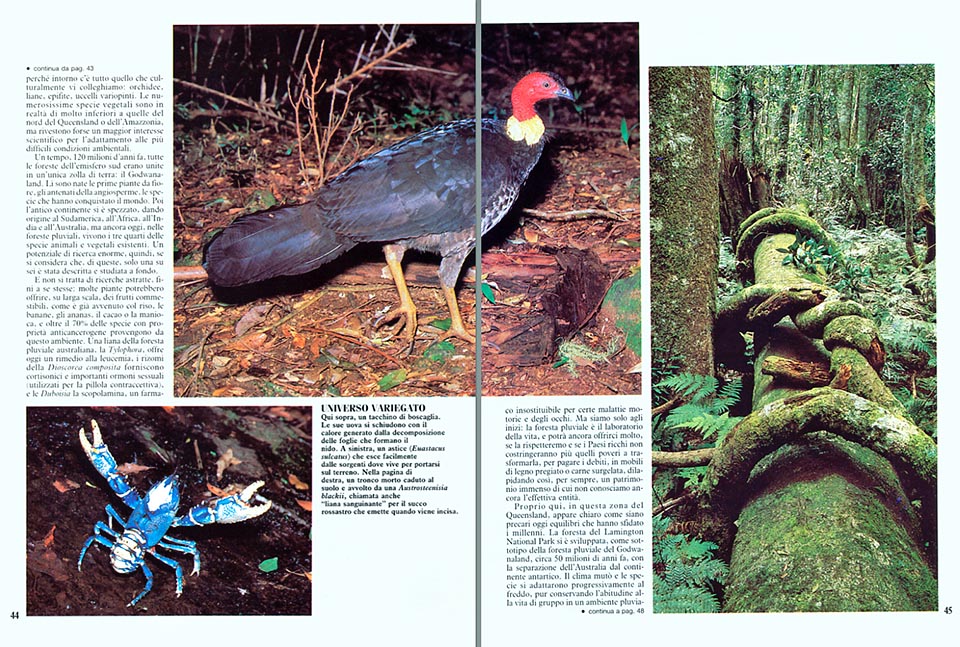

A red and blue crayfish (Euastacus sulcatus) comes, threatening, towards me, with two enormous wide open chelae. I have just met an irascible prehistoric turkey. It was looking, as usual, for molluscs and small worms of the underwood, when it has been suddenly invested by a shovel of rotten leaves.

We are not underwater, or dreaming, but in Australia, in the Lamington National Park, in a rainy sub-tropical forest, not far away from Brisbane.

Every year, at this time, in spring, it’s the usual story: the males of the brush-turkeys (Alectura lathami), become unbearable. They hardly tolerate the intrusion of the females, just good for laying eggs, and are rummaging the underwood incessantly.

They care the brooding, but, unlike the other birds, the do not sit on a nest: they pile up the leaves in heaps even taller than one metre, and wait for the rain.

Then, for weeks, they turn them, and turn them again, so that they are well wet, and if the rapid decomposition causes a fermentative explosion, they dig tunnels at various heights. They check them several times a day, by slipping through them, very professionally, the head, beak wide open, and when they feel that the temperature is more than 30 °C, they show the females where the eggs lay.

These ones are buried, forgotten for ever, like those of the reptiles, and 7-12 weeks later, the new born will have to open themselves, dangerously, a passage through the rotten leaves and to get off by themselves.

My crayfish, in the meantime, has reached a pond and, disdainful, washes itself in the running water.

As a frame, palms, waterfalls, and gigantic green “nests”. These are epiphyte ferns, enormous tufts of Platycerium and Asplenium australasicum. They hang from branches loaded of mosses, and orchids, between very long lianas, which look, upwards, for the light, with spiral movements. They have a diameter of more than 20 cm, and roll up centenarian trunks. A Blood vine (Austrosteenisia blackii), so called for the reddish liquid it emits when cut, has knocked down a giant, and now they decompose, together, on the humid soil.

Some Nipple figs (Ficus watkinsiana), up to 45 metres tall, present a strange, hollowed trunk. They are specimen born on the trees of the forest from seeds carried by the birds. They have reached discreetly the soil, with a long thin pendulous root, and then, little by little, have strangled the host with a tangle of aerial roots.

When this dies, its wood disappears, and the roots of the fig, uniting on the sides, form a sort of a big hollow trunk.

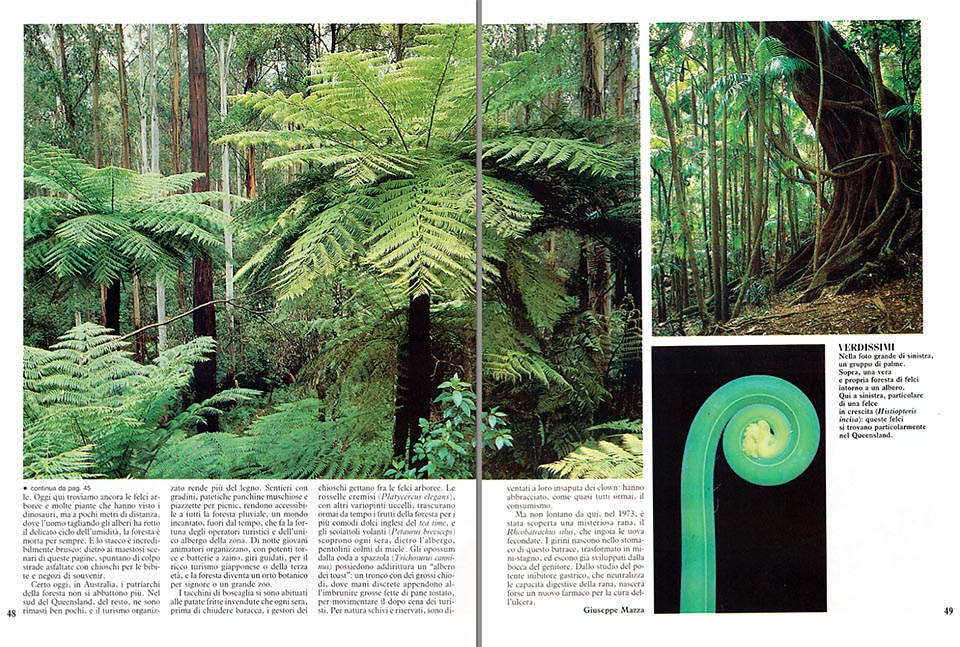

The palms (Archontophoenix cunninghamiana), grow very thick in the warmest zones of the forest, whilst the majestic Nothofagus and the araucarias dominate the most elevated locations.

But the constant contribution of streams and waterfalls, the rainy forest of the Lamington National Park makes large reserves of water between Christmas and Easter, and then, self-aliments them: the vapour reaches the thick green vault and then falls, drop after drop, for months.

More to the north, towards Cape York and New Guinea, in the tropical forest, they record 5.000 mm of rain per year; here, only 1.800 (in Italy, the annual rainfall varies between 500 and 3.000 mm, depending on the area, with 900 mm in Rome), but the evaporation is lesser and the plants take advantage, often, of the fogs.

It is cool, at 1.000 metres of altitude the lowest temperatures swing between 0 °C and 15 °C, but we still have the feeling of being in the Tropics, because around us there is all what we culturally connect to them: orchids, lianas, epiphytes, many-coloured birds, and, especially, a huge abundance of species.

Even if very numerous, they are, in reality, much less than those of the north of Queensland and of the Amazon, but they have maybe a better scientific interest, due to their adaptation to more difficult environmental conditions.

1.200 millions of years ago, all the forests of the austral hemisphere were united in a unique part: the Godwanaland. In that area were born the first flower plants, the ancestors of the angiospermae, the species which have conquered the world. Then, the old continent parted, originating the South America, Africa, India and Australia, but still now, in the rainy forests, do live the 3/4 of the animal species and of the existing vegetables.

An enormous potentiality of research, if we consider that, of these, only one of six has been fully described and studied. And it is not matter of abstract researches, self finalized: many plants might offer, on a large scale, edible fruits, as it has already happened with the rice, the bananas, the pineapple, the cocoa, or the cassava, and more than the 70% of the species with anti-cancerous properties, are coming from this habitat.

A liana of the Australian rainy forest, the Tylophora, offers nowadays a treatment against leukaemia, the rhizomes of the Dioscorea composita provide cortisone products and important sexual hormones (the contraceptive pill), and the Duboisia, the scopolamine, an irreplaceable drug for certain motion and eye diseases.

But we are only at the beginning. The rainy forest is the laboratory of the life, and will still be able to give us plenty, if we shall respect it, if the rich nations will not oblige any more the poor ones to transform it, in order to pay the debts, in furniture of value wood, or deep-frozen meat, thus dissipating, for ever, an immense patrimony of which we do not yet know the entity.

Rightly here, in this area of Queensland, it is evident how are today precarious the equilibria which have defied the millennia. The forest of the Lamington National Park has developed, like a sub-type of the rainy forest of the Godwanaland, about 50 millions of years ago, with the separation of Australia from the Antarctic continent. The climate changed, and the species adapted progressively to the cold, even conserving the habit to the life of group in a rainy environment.

Nowadays, we still find here the arboreal ferns and many plants which have seen the dinosaurs, but a few metres far away, where the man cutting the trees has broken the delicate cycle of the humidity, the forest has died for ever. And the separation is incredibly abrupt: behind the majestic sceneries of this article, suddenly appear asphalted roads, with refreshment booths and souvenir shops.

By sure, nowadays, in Australia, the patriarchs of the forest are not any more fallen. In the south of Queensland, on the other hand, very few of them have remained, and the organized tourism is more remunerative than the wood. Footpaths with steps, pathetic mossy benches and small clearings for picnics, make the rainy forest acceptable to everybody, an enchanted world, out of the time, which makes the fortune for the tourist operators, and the only hotel of the spot.

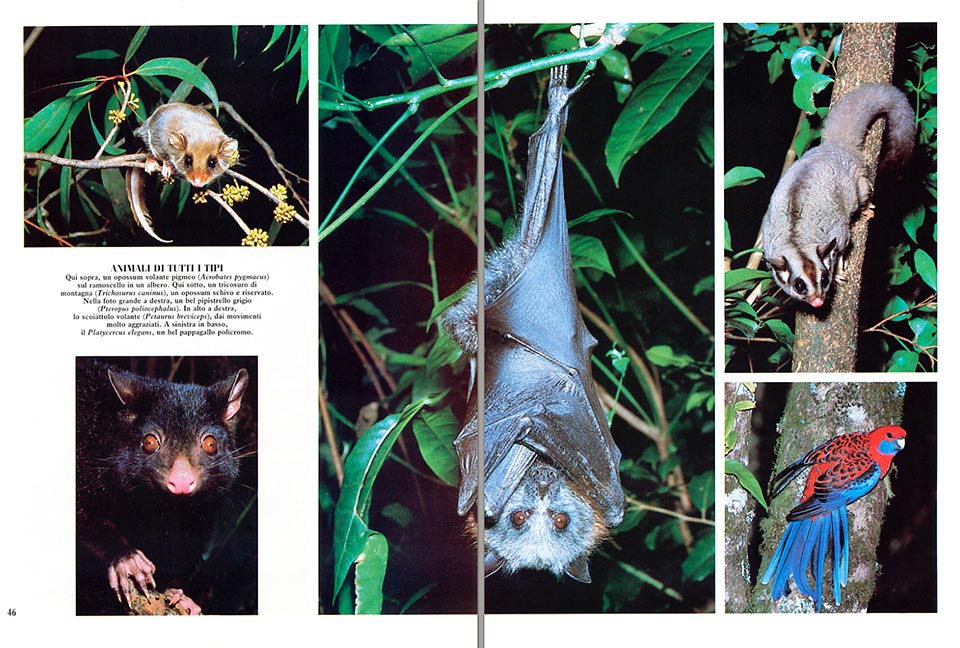

By night time, young animators organize, with powerful torches and kit-bag batteries, guided visits for the rich tourism of the third age, and the forest becomes a botanic orchard for ladies, or a huge zoo.

The brush-turkeys have got accustomed to the unsold French fries, which, every evening, before closing the shops, the managers of the booths throw between the arboreal ferns. The Crimson rosellas (Platycercus elegans), with other many-coloured birds, neglect, by now, the fruits of the forest, for the more convenient English sweets of the “tea time”, and the Sugar gliders (Petaurus breviceps), discover, every evening, behind the hotel, small pots full of honey.

The Short-eared possum (Trichosurus caninus), possesses even a “tree of the toasts”: a trunk with big nails, where discreet hands hang, at dusk, large toasted slices, in order to enliven the after dinner of the tourists. Coy and discreet by nature, they have become clowns: they have taken up, as everybody, the consumerism.

But, not far away from here, in 1973, they have discovered a mysterious frog, the Rheobatrachus silus, which swallows the fecundated eggs. The tadpoles come to life in its stomach, which is transformed in a sort of a mini-pond, and get out from the parents’ mouth, when already developed. From the study of the powerful gastric inhibitor, which neutralizes the digestive capacities of the frog, will come to life, maybe, a new drug for the treatment of ulcer.

SCIENZA & VITA NUOVA – 1989