Text © DrSc Giuliano Russini – Biologist Zoologist

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Unlike the other anurans, the tree frog, at times, is active also during the day © G. Mazza

Amphibia

The Amphibians (Amphibia) form a class of tetrapod Vertebrates. Aquatic and pisciform during their larval life; terrestrial as adult, when they frequently return to the water for performing their vital cycle, and for this reason defined “with amphibiotic life”.

This denomination matches also with a physiology of the development, to which corresponds a heavy metamorphosis, in relation to which they pass from a branchial respiration, when young, to a lung one when adult.

However, some species keep the gills for the whole life, both normally, as well as, exceptionally, in particular environmental conditions.

Not all biologists are in agreement about the systematic positioning of some orders of this class.

Howsoever, in principle, most of the scholars subdivide the Amphibians (Amphibia) in three fundamental orders:

►Apoda, called also Gymnophiona and, in the past, Ceciliforma. The members of this order are limbless and are similar to the snakes; an example is the Ichthyophis glutinosus.

►Anura, tailless when adult (toads, frogs and tree frogs). Examples are the Xenopus laevis or the members of the species Racophorus.

►Urodela. The members of this order have a long and well visible tail with circular section. Examples are salamanders and newts, like the Pseudotriton ruber, the Salamandra salamandra, which is absolutely harmless, however considered in the popular tradition as poisonous and invulnerable to the flames, the Alpine Newt (Triturus alpestris), very common all over Europe, from the plains up to 3.000 meters above the sea level.

In phylogenetic and paleontologic terms, the amphibians, as fossils, are known to the biologists from the Devonian onwards.

The genus Ichthyostega, is particularly important, as it represents the link, let’s say, between the Amphibians (Amphibia) and the class of the Crossopterygian fishes (Crossopterygii).

After other biologists, the Amphibia, more precisely, should have evolved from a suborder of fishes, the Rhipidistia.

In the Permian Period, were much diffused the (Stegocephalia) or Labyrinthodonts (Labyrinthodontia), by certain authors considered as Labyrinthodont Stegocephalia (Stegocephalia labyrinthodontia), of which some had a huge structure, and also a powerful cuirass made by bony scales.

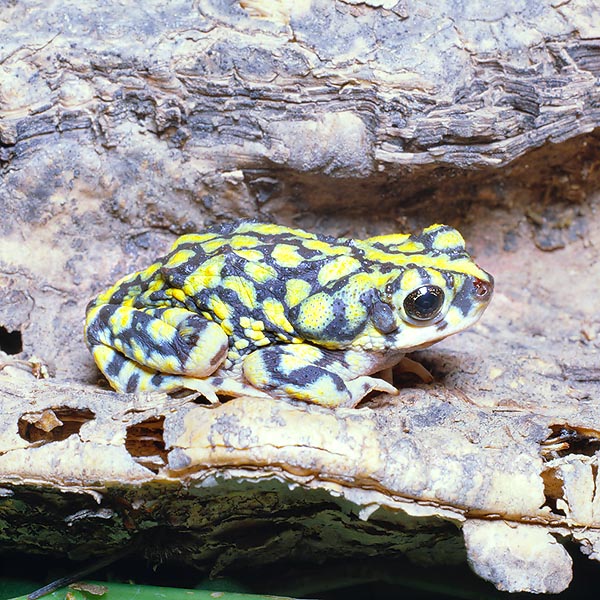

Pesotibes hosii, an arboreal blue with yellow dots toad. Everything is possible in the anuran world © Giuseppe Mazza

The presently extant species are about 2.000, 24 of which present also in Italy, but some of them can be found also in the pluvial tropical forests of the African, South American and Asiatic tropical and subtropical belts, as well as in the Australian and American regions.

Usually, their alimentation, in juvenile age, is composed by plankton, whilst it becomes much varied when adult: insects, worms (oligochaetes, plathelminthes, nematodes, terrestrial and freshwater annelids), molluscs, crustaceans.

The geographic distribution of the amphibians is, therefore, almost cosmopolitan, which means that we can find them everywhere, in different densities, but in the Polar Regions and in extreme altitudes, as they are “heterothermic” animals.

They are obviously bound to the aquatic or at least very wet environments.

Some species may even reach the fifty years of life.

Finally, we have to remind that in some of them is present a strong regenerative process (also of the lens of the eyes, when damaged) of the amputated limbs, as it happens for some species of lacertids, capable to regenerate ex-novo the tail which they often, voluntarily, do amputate, for escaping from the bite of the predator which has caught it, “spontaneous caudectomy”.

Let us see now some morphophysiologic characteristics of the amphibians, of general type, before describing the order of the Anurans (Anura).

The Pipa pipa may be 15 cm long. The females carry the eggs encysted on the back © Giuseppe Mazza

Though, often, the appearance of the amphibians is not much different from that of the reptilians, for instance, when confronting the members of the apoda with some members of the ophidians (snakes), we realize that they somewhat differ from the last ones, among other things, for having a skin called “naked”, that is scaleless.

This skin is very viscous when touched due to the secretion of many glands spread throughout the whole body, which may be distinguished in “muciparous” and in “poisonous” or “granulous”. The last ones may secrete highly toxic or at least irritating substances.

Furthermore, in the epidermal layer as well as in the dermis, are present pigmented cells called “chromatophores”, responsible for the sudden changes in colour which are at the base of the phenomenon of “Batesian mimicry”. For the rest, the species which may present some bony formation on the skin are rare.

The blood circulation is simple in the larvae, double and incomplete in the adults, which means that the arterial and venous bloods are not separated, whence an insufficient oxygenation of the tissues. That is why the cutaneous respiration as well as that taking place through the buccal and pharyngeal mucosae have a great importance.

The reproductive process may follow different modalities or strategies: the fecundation can be internal or external; therefore the “de facto” coupling can even not happen.

The amphibians are usually “oviparous”, but there are instances of “ovoviviparity”: in such case, the eggs hatch in the cloaca of the females and alive young are delivered. In some rare instances, the “neoteny”, like in the Axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum), that is the capacity to reproduce already at the larval stage.

The Xenopus laevis was utilized as pregnancy test © Giuseppe Mazza

Anura

The name of this order comes from the fact that these amphibians, when adult, are tailless. Present all over the planet, but the Poles and some Oceanic islands, they are also called salientians, due to their typical jumping way of moving. From the taxonomic point of view, the order of the Anura is subdivided in five suborders, mostly based on the shape of the vertebrae.

►Suborder Archeobatrachia

The first suborder, also in the evolutionary scale, is that of the Amphicoela (Archeobatrachia), characterized by the possession of front and rear concave vertebrae, with the characteristic, considered as archaic, of having undivided vertebral bodies. An example is the genus Liopelma with the Hochstetter’s Frog (Leiopelma hochstetteri Fitzinger, 1861) 2 cm long, which lives under the stones, in the Coromandel peninsula, in the northern Island of New Zealand.

Others of this genus are the Archey’s Frog (Leiopelma archeyi Turbott, 1942) 2-3 cm long, a 38 million years old extant fossil and the Hamilton’s Frog (Leiopelma hemiltonii), 1-2 cm, maybe already extinct. In North America, there is only one species of this suborder, the Tailed Frog (Ascaphus truei), living in the cold mountain streams. The male has a copulatory organ by means of which it fecundates the female internally, thus avoiding that the seminal liquid gets dispersed in the current. The female lays the eggs after about eight months from the fecundation. This suborder has two families:

♦ Ascaphidae, four species with ribs and rudiments of caudal muscles. There are two genera, one in New Zealand and the other in North America, both very rare and of small size.

The multicoloured Bombina variegate is very common in Italy © Giuseppe Mazza

♦ Rhinophrynidae, one species only: the Mexican Burrowing Toad (Rhinophrynus dorsalis 6 cm long, living in the thickets and the savannah in the coastal plains of Mexico and Guatemala.

►Suborder Opisthocoela

The suborder Opisthocoela, includes anurans with convex vertebrae on the front and concave on the back.

To this belong the following families:

♦ Pipidae, 15 species. These are highly specialized aquatic anurans, which rarely move on the ground.

Only the larvae, paradoxically, are provided with ribs.

The jaws are toothless and all species do not have the tongue; at times the eyelids are present.

The absence of the tongue, for some authors, is a character for which these amphibians ought to be classified in a separate family, the Aglossae.

Examples are the Pipa (Pipa pipa) 15 cm long, and lives in Trinidad and in South America, from Venezuela up to Brazil and Peru.

In spring, the female places the eggs on its back, which has become spongy, and the male fecundates them.

The eggs grow, closed in the cavities which have formed, and are covered by a corneous membrane.

After about three months the young leave the “incubation chamber” and swim freely and lively on the water surface, keeping close to the mother.

A Hyperolius marmoratus in the wild among the petals of a Plumeria rubra © Giuseppe Mazza

Another species is the Platanna or African Clawed Frog (Xenopus laevis) which reaches the 10 cm of length.

It has claws on the three fingers of the hind limbs, some teeth on the mandible and a tentacle under each eye.

The female lays its eggs in the calm water and does not care them.

Of great scientific importance, it was utilized in the fifties as a pregnancy test.

Injecting urine of a pregnant woman in a female of Xenopus laevis, it may be seen how this one lays the eggs in a span of 5 to 24 hours, this because the effect of the human chorionic gonadotrophin (beta-HCg), present in the urine.

Nowadays, the Xenopus laevis is reared in laboratory for embryologic researches.

♦ Discoglossidae, this family owes its name to the discoid form of the tongue. It counts 10 species living in Europe and in Asia Minor. They have toothless mandible and ribs which are present all the life long.

An example is the Mediterranean Painted Frog (Discoglossus pictus), which lives in South France, part of the Iberian Peninsula, the North Africa, Sicily and Malta.

The Scaphiopus couchii lives in Sonora Desert. The tadpoles metamorphose in 2-3 weeks only © Mazza

It looks like a frog, with the back yellow or reddish, spotted by brown dots with pale edges. It lives in the cold mountain waters and in the pools of brackish water.

An interesting species, spread in central-western Europe, is the Common Midwife Toad (Alytes obstetricans ), reaching the 4,5 cm of length, with a uniform grey-ashy colouration.

The head is flattened, the eyes are big, the nares are not visible and the skin on the back is wrinkled.

At the time of the copulation, the female lays 120-140 eggs, wrapped in gelatinous strings, where also some spots of blood can be seen; the male fecundates them and collects them around the hind legs, where they remain till the opening; at this point, it moves towards the nearest water point, dipping there the back legs so that the larvae are freed.

We have then to remind the Yellow-Bellied Toad (Bombina variegata), living in central Europe, but very common also in Italy.

Its scientific name is due to the yellow and orange coloration of the belly, whilst the back is olive-grey or brown.

The skin can emit an irritating substance, also for the man. It defends from predators assuming the mimetic form of a dead, with the belly on the ground, the fore limbs bent on the eyes and the back ones raised.

The Megophrys nasuta lives in Borneo, Java, Sumatra, Malaysia and Thailand forests © G. Mazza

♦ Rhacophoridae, called also Moss Frogs. It’s a family with hundreds of species.

They live in the Tropics, in Africa, in Madagascar and in East Asia; they have adapted to the arboreal life like the tree frogs, they have palmate back legs.

A known example is the Hyperolius horstockii, 4,5 cm long, common in southern Africa, hidden between the grasses of the genus Arum, or the Marbled Reed Frog (Hyperolius marmoratus), 2-3,5 cm long, of central-southern Africa, with different drawings on the skin, depending on the zone and the sex.

The Grey Foam-nest Treefrog (Chiromantis xerampelina), reaching the 8 cm, lives on the trees in the bushes and the woody savannahs of south-eastern Africa, even far away from aquatic environments.

►Suborder Anomocoela

The species belonging to the suborder of the Anomocoela, are characterized by having concave pre-sacral vertebrae only on the front, or biconcave, with free inter-vertebral disks. The coccyx is fused with the sacral vertebrae, or articulated with them by means of a condyle. There are no free ribs.

They have one family only, the Pelobatidae, with 54 species. They are small toads equipped with small teeth, living in Eurasia, North Africa and North America.

Examples are the Common Spadefoot (Pelobates fuscus), of 4-8 cm, living in central and eastern Europe and in western Asia, and the Western Spadefoot (Pelobates cultripes), 5-8 cm long, living in south-western Europe and in western Morocco. It is similar to a toad, but good jumper and exceptional digger. If upset, it secretes a liquid with a pungent smell and takes an aggressive look.

With its strong jaws, the Ceratophrys ornata kills and eats also mice © Giuseppe Mazza

Its tadpoles may reach remarkable sizes (10-18 cm). When adult, the body is of olive or greyish colour, with the back covered by brown spots and dotted red.

The Couch’s Spadefoot Toad (Scaphiopus couchi) spread from the south-western USA to northern Mexico, is found also in the Sonora Desert, between the cacti, taking shelter from the heat underground, during the day.

When it’s raining, they gather around the ponds.

The tadpoles come to life after three days and metamorphose in 2-3 weeks.

The Long-nosed Horned Frog (Megophrys nasuta), common in the forests of Borneo, Java, Sumatra, Malaysia and Thailand, reaches the 13 cm and strikes the attention due to its odd horns.

►Suborder Procoela

The Suborder Procoela includes numerous species, distributed in almost all the world.

The Procoela have concave frontally and convex behind vertebrae.

They are divided into six families:

♦ Leptodactylidae, about 650 species, with an uneven geographical distribution. In fact, they are present both in South America and in southern USA, in Australia and, after some biologists, also in South Africa. We remind, among these, the Leptodactylus labialis, with oval tongue and lips surrounded by white, living in the meadows and in wet locations, from Mexico to Texas.

A toad (Bufo bufo) inflates to look bigger and scare off the intruder © Giuseppe Mazza

The eggs may be spawned out of the water, as they are placed in a foamy spot at high contents of humidity.

During the dry season, they hide into the depths of the ground. Some species lay their eggs in underground dens and trust in a possible shower for getting the possibility that the eggs may develop.

At times, the larvae transform in adults before that all the rainwater has evaporated. An example is the Southern Corroboree Frog (Pseudophryne corroboree) 2,5-3 cm long, living in New South Wales, in dens dug in the wet mud in marshy areas, above the snowline.

Other interesting species is the Argentine Horned Frog (Ceratophrys ornata), common in northern Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, Brazil and Uruguay. It measures even 13 cm, and camouflaged in the under-wood catches and swallows, without any hesitation, all what passes by, even mice, which it kills with its powerful jaws.

♦ Bufonids (Bufonidae), 300 species. The do not have upper teeth. Some genera, like the well known Bufo, which includes 250 species, are present in all the continents, but Australia.

They are terrestrial, they move by nightfall and before dawn. They are specialized in seizing insects, by means of the tongue to which the insects adhere. A typical example is the Common Toad (Bufo bufo),) living also in Italy but Sardinia, in Europe and in Asia up to the Baikal Lake, carries a stable and sedentary life under roots or tree stumps.

The Bufo quercicus is a small American toad of 19-33 mm only © Giuseppe Mazza

The warts, placed on the back, secrete poison.

The body is squat and solid, the legs are short and robust and the back has a greyish-brown or olive colouration, becoming paler on the belly.

In spring, the male, whose size is about half of the female’s, which may reach the 13 cm, develops inter-digital membranes and the adhesive callosities utilized for the coupling do appear, so increasing the sexual dimorphism, which is not, anyway, definitive, but temporary in relation with the mating season.

Reason for which the biologists call it “seasonal sexual dimorphism”.

The tadpoles are small and become adult in about 12 weeks.

The common toad may lives up to 40 years and is easily tamed.

♦ Brachycephalidae, the Saddleback Toads, several species spread in Central and southern America, of which we quote the Darwin’s Frog (Rhinoderma darwini), not to forget the Cuban Sminthillus (Sminthillus limbatus), which reaches the 10 mm of length and of the Golden Dart Frog (Phillobates terribilis), with a thin body, brown on the back and red on the belly, with the two colours separated by a yellow strip.

Grace and elegance in the Hyla meridionalis, common in the Monte Carlo Sporting gardens © G. Mazza

♦ Hylids (Hylidae), European Tree Frogs, almost 800 species. The tree frogs are adapted for living on the trees (arboreal life); their fingers, in fact, have a particular structure which facilitates their climbing.

The family, which includes terrestrial and aquatic species, includes the great genus Hyla, with more than 350 species, spread worldwide, but South Africa, southern Sahara and eastern Polynesia.

A typical specimen is the European Tree Frog (Hyla arborea), 5-8 cm long, spread in Europe, Asia and North Africa.

Usually of a bright green colour, it may change rapidly of coloration (for camouflaging or utilizing the colour as “aposematic” message), becoming yellowish or grey-yellow.

It carries mainly a nocturnal life.

During the day, it takes shelter on the tops of the trees, which it easily climbs.

It nourishes of insects, thus being helpful to the agriculture. The body is not too big, the forelimbs are rather short, whilst the hind ones are long, with palmate fingers and provided of adhesive disks on the tips.

♦ Microhylidae, about 468 species. Little known family, formed by species living either in holes in the soil, or on the trees, in the Tropics of the Old and New World, Oceania included, excluding western Africa.

The Phrynomerus bifasciatus can slightly move the neck, rotating the head © Giuseppe Mazza

They come out from the eggs in a very advanced development stage, or even already metamorphosed.

An example is the Mozambique Rain Frog (Breviceps mossambicus), 5 cm long, living in South Africa, in holes dug in prairies and bushes.

Another example is given by the Tomato Frog (Dyscophus antongilii), endemic to Madagascar, in Malagasy language is known as “sangongong”.

It has a bright red skin capable to secrete a whitish substance, irritant for the man, which the animal emits when feeling in danger, as primary defence.

The females may exceed the 10 cm of length and the 200 g of weight, the males are smaller, reaching the 6-8 cm of length, sexual dimorphism.

We remind also the Eastern Narrowmouth Toad (Gastrophryne carolinensis) of south-eastern USA, greedy and big consumer of ants and of termites; the Banded Rubber Frog (Phrynomerus bifasciatus) of southern Africa, which well climbs on the trees trunks and can slightly move the neck, turning the head, and the Asian Painted Frog (Kaloula pulchra) of South-eastern Asia.

♦ The Grassfrogs (Centrolenidae) form the smallest family of the suborder of the (Procoela), which includes individuals with green body, pigment which can be found also in the bones. They have adapted to the arboreal life.

The Rana esculenta is common in all central-southern Europe and Italy, but Sardinia © Giuseppe Mazza

►Suborder Diplasiocoela

The broad Suborder Diplasiocoela have biconcave abdominal vertebrae, pre-sacral procoelous vertebrae and sacral vertebrae articulated with the coccyx, by means of a double condyle.

Similarly to the Procoela it includes several species spread in the world.

The family of the frogs (Ranidae), belongs to it with about 470 species.

This group, spread in all continents (but the Antarctic Pole), does not have specializations apart that for the jumping, which is, however, common to all the Anura.

It includes the genus Rana, with 200-300 species, all presenting a typical indent on the margin of the tongue.

Some, like Marsh Frog (Rana ridibunda) and the Edible Frog (Rana esculenta), are aquatic and have jugular vocal sacs.

Another well known example is the European Common Brown Frog (Rana temporaria) cm long, amply spread in Eurasia, up to the Arctic coasts. The vocal sacs are hidden under the skin of the throat.

Distinctly terrestrial, the Rana dalmatina loves the European woods close to the water © Giuseppe Mazza

The individuals of the genus Rana are distributed everywhere, but South America and Australia.

They are characterized by having an evertile tongue, attached to the front portion of the buccal floor, engraved at the back extremity.

For what the dimensions of the body and the pigmentation are concerned, there are quite many variants. Also the habits differ: some individuals carry on arboreal life, others are aquatic and others are terrestrial.

The Edible Frog (Rana esculenta) with its slender head, the body green on the back, with darker spots or paler stripes and white belly, lives in Italy (but Sardinia) and all over central-southern Europe.

The eggs are emitted in number of 5.000-10.000 each time, wrapped in a gelatine capsule, by means of which they remain suspended to the aquatic plants.

The metamorphose completes in about three months.

The edible frog carries on a nocturnal life and prefers the still waters, or even stagnating, where the vegetation is particularly abundant. It nourishes of small insects, molluscs and worms of which it is a skilful and greedy hunter.

The North American Rana catesbeiana reaches the 20 cm and has a sound like a moo © Giuseppe Mazza

Lastly, the Agile Frog (Rana dalmatina), living in the plain meadows and woods; specific details will be given from time to time in each text.

Between the greatest species, we remind the famous Goliath Frog or Giant Frog, or Cameroun Frog (Golia conraua).

This huge frog lives in the tropical forests of West Africa, reaches the 40 cm of length and even the 2-3 kg of weight!

Of remarkable size is also the Bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) of North America, which owes the name to the cry it emits, similar to a moo.

To end, we remind two families which do not have a specific suborder, but simply belong to the Anura :

♦ Atelopodidae, with 26 species. They are small anurans, lively coloured, which live in the streams in the under-wood of Central and South American forest.

There are two genera only. Some species walk instead of hopping.

In one species, the Atelopus stelzneri, the larvae come to life 24 hours after the deposition of the eggs. The Panamanian Golden Frog (Atelopus zeteki), 6 cm long, living in the streams of Panama. It can neither swim nor hopping; its skin is venomous.

The Atelopus varius lives in Costa Rica and is active by day. The skin is soaked of venom © G. Mazza

The showy Costa Rican Variable Harlequin Toad (Atelopus varius) lives in Costa Rica and is active during the day.

Also its skin is literally soaked of venom and therefore it has no natural foes, but a parasitic fly which lays its eggs on its thighs. These ones, while growing, penetrate the flesh and eat it alive, in spite of the venom.

This species is also in serious decrease also due to the human activities and the recent climate changes.

♦ Dendrobatidae, with several species, called Poison Arrow Frogs, with varied and brilliant colours.

Their skin, rich of venom glands, emits a secretion (or better, a poisonous cocktail), utilized by the Amazonian Indians or by other populations of South and Central America, like the Chocho, indigenous people of the Mexican forests of the state of Oaxaca, for dipping the tips of their arrows which are then utilized in hunting especially monkeys and tapirs.

They cruelly shove them, alive, on a stick, and place them close to a flame so that they secrete, until the last drop, the precious venom for their deadly blowpipes.

Morpho-physiologic characteristics, ecology

The skin of the Dendrobates is rich in venom glands. The secretion is used by Indio hunters © G. Mazza

Usually, the anurans are amphibians of modest size, between the 4 and 8 cm.

However, there are forms whose dimensions, for ecologic and zoogeographic reasons, remarkably deviate from the average.

Some herpetologist and bathracologist biologists have found 60 cm long specimens in western Africa of the previously mentioned Goliath Frog (Golia conraua) which is, at least until now, the greatest terrestrial anuran amphibian known to Biology. On the other end, the Cuban Sminthillus (Sminthillus limbatus) hardly reaches the 10 mm of length.

Usually, in the Anura the head is triangular, flattened, with enlarged base; the nares are small, the mouth is ample, the protruding eyes, with a particularly developed nictitating membrane, permit to some specimens to have a much wide field of vision, up to 360°. The eyeballs may be inverted in the eye socket.

The ear does not have auricles and the tympanic membrane is visible behind the eyes. The teething is variable: at times the teeth are present only on the upper jaw; at times they are totally absent (genus Bufo).

In only one genus they are present on both jaws and there are species equipped with “palatine” teeth. In any case the teeth do not hold a masticatory function, but their use is just for retaining the food. Most frequently, there is a fleshy tongue, evertile from the rear to the front, fixed, in the anterior portion, to the buccal floor.

The eardrum of the anurans is just behind the eye © Giuseppe Mazza

The trunk is stocky and carries four robust limbs.

The forelimbs are short, whilst the hind ones are long and muscled, typically formed for jumping.

Femur, tibia and foot do all have the same length.

In resting position, the hind limbs are folded, but they are quickly stretched when the animal gets ready to effect the leap, furnishing a forward motion to the whole body.

The forelimbs are used as a support during the jump and soften the fall.

The hands and the feet differ depending on the habits, in such extent to offer a criterion for the classification to the taxonomic biologists.

At times, both the fingers of the back limbs (in number of 5), and those of the fore limbs (in number of 4), are united by membranes, which are usually present only on the fingers of the rear limbs.

The function of these inter-digital membranes is to help in swimming. This happens by means of alternate bending and stretching of the back legs, whilst the fore ones remain close to the body, in order not to cause any friction.

Rana pipens. Femur, tibia and foot of the same length. Inter-digital membranes for swimming © G. Mazza

The terminal part of the fingers may be sharpened, may have a button-like expansion, and may be equipped in the lower part of adhesive disks, or of cutting tubercles and horny edges for digging tunnels in the ground.

The epidermis, as briefly said in the introduction on the Amphibia, is naked, covered by a slight horny layer. Only rarely are present horny or bony thicknesses. The mucous glands are numerous, especially behind the orbits of the eyes and along the trunk, in order to keep the skin wet.

The colour varies thanks to the “chromatophores” which allow at times the mimicry with the environment.

With classification purposes, also the skeletal frame, partly osseous, partly cartilagineous, is examined besides the particular structure of the fingers.

The spine is almost always formed by nine vertebrae, the last ones being blended together, forming the bone of the coccyx, or “urostyle”.

The shape of the vertebrae represents the main characteristic after which the order of the Anura is subdivided in the aforementioned five suborders.

Depending on the shape of the pectoral girdle, the Anura are subdivided in “firmistern” with the two epicoracoids fused at the centre of the thorax, and “arciferous”, with the two epicoracoids free and over-posed. The ribs are present in the most archaic forms. Always for these archaic forms, we have to notice the typical fusion of the “radius” with the “ulna” and of the “tibia” with the “fibula”.

The colour of Hyla cinerea may change instantly due to its chromatophores. A mimicry device, but also for sending visual messages © Giuseppe Mazza

The alimentary canal is formed by the larynx, followed, in the order, by the esophagus, the stomach, a middle intestine developing in many loops, and the terminal intestine leading to the cloaca.

A Rana utricularia albina. This phenomenon touches also the anurans world © Giuseppe Mazza

The respiration is branchial in the larval forms. In the adult ones there are two lungs which expand thanks to the combined action of the tongue and of the abdominal muscles.

Intense gaseous exchanges happen through the skin and through the buccal mucosa, which is strongly vascularised and perfused.

The blood circulation is simple and not complete at larval stage, double and not complete in the adults.

The venous blood flows through the venous sinus, then through the atrium, divided into two parts by an interatrial septum and then goes through the ventricle, the bulb and finally the arterial sinus.

The truncus arteriosus splits into four couples of “aortic arches”, which regress with the change from the branchial to the lung respiration, originating the carotids and the lung arteries. A bifurcation of the last ones originates the cutaneous arteries.

The lung arteries are united to the aortic arches by means of the “Botallo’s duct”.

In the venous system there is a posterior vena cava and an abdominal one. Furthermore, there is a hepatic and renal portal system.

In comparison with the Fishes (Pisces), from which the Amphibia, and consequently the Anura belonging to them, come zoologically in direct line, there is a greater development of the telencephalon (the cerebral hemispheres), whilst the cerebellum is reduced.

Always comparing with the Fishes, the ear has an evolution of the “lagena” (a structure which, in the inferior vertebrates, appears as extroversion of the sacculus, which is part of the membranous labyrinth. In the mammals, this is part of the cochlea).

The endolymphatic duct forms some diverticles diverging in the “pleuroperitoneal” cavity, where they originate small sacs containing calcareous secretions which are useful for perceiving the balance and the position in the space. The middle ear is formed by the tympanic cavity which, through the “Eustachian tube” communicates with the pharynx and is limited, outwards, by a tympanic membrane.

The vocal sacs may be jugular, like for Hyla gratiosa, or on the sides of the mouth © Giuseppe Mazza

The tympanic cavity contains the “columella auris”, which has the same embryologic derivation as the stapes of the mammals.

The skin is rich of a thick net of sensitive tactile nervous termination.

At the larval stage, there are cutaneous sensitive buttons as well as the organ of the lateral line, which regresses during the metamorphose.

The gustatory papillae are distributed on the tongue.

Adjacent to the olphatory apparatus, with subsidiary function, stands the “Jacobson’s organ”, a couple of diverticles of the wall of the two nasal cavities, which in this order is well developed, with the function to perceive the presence of smells in the air in concentrations of the order of parts per million (p.p.m.).

The anurans have vocal chords and a larynx. In the males of almost all genera are present dilations of the mucosa, called “vocal sacs”, which work as resonators and render perceivable, as recognition signals and sexual attraction, the croaking at long distances, during the heat season. These vocal sacs may have a simple conformation, like the tree frog, and may be located in jugular position, or they may be placed on the sides of the mouth; in such case they are flexible outwards, as is the case of the Rana esculenta.

All Anura have separated sexes. An exception stays in the males of the Bufonidae, where it is found a partial hermaphroditism due to the presence of the “Bidder’s organ”, rudimentary ovary, whose trace is found also in the females.

Bufo viridis. A partial hermaphrodism due to Bidder’s organ is found in the toads © Giuseppe Mazza

In some species a remarkable grade of sexual dimorphism can be noticed, due to secondary sexual characters, which becomes more evident during the period of the reproduction.

In the males of the toads, for instance, the fingers of the hind limbs cover with callosities, called by the zoologist biologists “copulatory spicules”, which facilitate the adherence of the bodies during the coupling.

The masculine genital apparatus may have a connection with the renal tubules, where arrive the afferent spermatic ducts. From the renal tubules, the sperm is carried outside through the ureters. If the connection is missing, then there is a distinct spermatic duct which reaches the cloaca. At the level of the testicles are present “fat bodies”, real and true organs which provide to the nourishment of the masculine gonads.

Usually, the copulatory organ is missing. Therefore, either the sperms are released outside in the “exogenous” reproduction typical of the Anura, or it is sprayed in the females, after the juxtaposition of the cloacae, in the “endogenous” reproduction in members belonging to other orders of Amphibia.

In the females, the ovules pass from the ovaries to the cloaca, through the “Müller’s ducts”. Sometimes, the Müller’s ducts expand in proximity to the cloaca originating a rudimental ovary, the “ovisac”.

Biologic cycle

In the Anura the coupling is not preceded by a traditional courting or a nuptial parade. At most, the males try to attract the females emitting long lasting nocturnal croaks. The fecundation is external: the male ties the female holding it before the back limbs or in the underarms.

Litoria cerulea. The skin of anurans has a thick net of nervine, sensitive and tactile terminals © G. Mazza

After many zoologist biologists, the centre from which generates the stimulus to the copulation in the females is placed in the cervical cord. The female raises the body, curves the back, stretches the back legs and begins the emission of eggs. The male gets, from the characteristic position of the partner, the signal for the emission of the sperm.

Between the Anura there is only one ovoviviparous genus of Bufonids, an exception is also the Tailed Frog (Ascaphus truei), which lies the eggs long time after these have been fecundated internally. The eggs emitted by each fecundation are usually very numerous, even 25.000 in the Common Toad (Bufo bufo). However, in western India there is a species which produces one egg only.

A gelatinous mass surrounds the eggs which, depending on the species, may remain gathered in clusters or be subdivided in smaller groups.

In the Anura holding an ovisac (a primitive uterus), there is an emission of gelatinous strings which contain few eggs each.

Both the mating and the deposition happen usually out from the water. There are, however, some exceptions; like for instance the Eleutherodactylus which lies its eggs on the solid ground from which the tadpoles get out once completed their metamorphose. Some tadpoles may develop on the bifurcations of the branches of the trees, where small pools of water form; others may remain stuck to the body of the father or the mother.

The female of the Aparo (Pipa americana), commonly called Surinam Toad or Surinam-Toad, carries the eggs in special cavities on the back; the male of Darwin’s Frog (Rhinoderma darwini), transports them in the vocal sacs until the time of the metamorphose.

Coupling Bufo bufo among strings of lied eggs © Giuseppe Mazza

The segmentation of the fecundated ovules is usually “total unequal”.

Embryologically, it means that the distribution of the yolk, which affects the type of segmentation of the ovules, is asymmetric: that is, it forms a pole called “animal” and another called “vegetal” or “vitellin” or “vegetative”, most rich of yolk.

This causes a sort of segmentation, which will form blastomeres of different sizes, greater, “macromeres”, smaller, “micromeres”, and for this defined as “unequal”.

In embryology, the eggs of the animals are classified depending on the type of cleavage and of distribution of the vitellin or yolk or deutoplasm.

The eggs of the mammals, for instance, have little yolk as the embryo gets its pabulum mainly from the placenta, and are called Oligolecithal or Isolecithal, seen that the yolk is evenly distributed.

In this case, the cleavage is of the type “total adequal”, with formation of blastomeres having the same size.

On the opposite side, the eggs of the birds and of the reptilians have a lot of yolk and are big, so much to be called Telolecitic.

Here, the segmentation is defined as “Meroblastic”, that is partial, as the enormous quantity of deutoplasm slows down the process of cleavage till its stop, therefore rendering it only partial.

For the axillary mating, the male gets membranes and callosities on the fore limbs © Giuseppe Mazza

Owing to this, there will be the formation of a particular discoid structure “embryonic shield” for the migration of the cyto-blastomeres formed, and this will have an equivalent function as the “embryonic node” of the mammals.

Actually, also an order of mammals, the Monotremes (Monotremata), subclass Prototherians (Prototheria), like the Platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) or the Echidna, or Spiny Anteater or Short-beaked Echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus), like other species of this order, have a segmentation of the eggs of this type.

This had generated the doubt to the biologists of the XVIII-XIX centuries, that they should come directly from the reptilians and that, maybe, also the human being had this type of zoological derivation. In fact, they were talking of “ Homo reptilis ”.

Those of the insects are defined as “Centrolethic”, here the cleavage is “superficial”. Last, the amphibian’s ones are called also Mesolecithic or Medio-lecithic: they have a quantity of intermediate yolk, which spreads in uneven way during the rotation of the ovule in the oviduct.

One part of the egg will be rich of growth and differentiation factors which will rule the embryogenesis and will form the point where the embryo will come to being, the “embryonic node”; in this part there is very little vitellinum or yolk, whilst all the rest concentrates on the opposite side for generating a sort of nourishing reserve for the developing embryo. The first pole is defined as Animal or half Animal, because it is where the embryo generates, and the second is the Vitellin, Vegetal or Vegetative, because it allows the animal to vegetate, that is to grow up by nourishing.

The just laid eggs of Rana esculenta are only 1-2 mm long and are half pale and half dark. After few hours they rotate in order to place the clear pole downwards. Then the wrapping gelatinous membrane swells of water, thus multiplying their diameter © Giuseppe Mazza

The larva which originates remains during the first days inside the gelatinous mass which wraps the eggs. The respiration of the larvae happens by means of outer gills which quite soon are covered by a cutaneous excretion.

Then, the mouth shapes. It will have a couple of horny jaws.

Around the buccal cavity appear small horny tubercles which, at this stage, offer a valid means of classification.

A dorsal fin and an anal one take shape on the tail.

The eyes, roundish and without eyelids, become functional; also an organ of the lateral line appears, but this will disappear later on. This last represents a crux of the phylogenetic derivation of the amphibians from the fishes.

At this point, the larva assumes the status of “tadpole”, moving freely in the water, nourishing of algae and of other vegetal aliments.

The last stage of the development, the one leading to the stage of “adult”, takes place in a period going from two to three months, for the European species.

The back limbs appear the first, then the fore ones, in the same time the gills and the tail atrophy, whilst the lungs take shape.

The horny jaws disappear and the mouth takes the typical structure of the adults. The organ of the lateral line disappears. The intestine shortens due to the passage from a vegetarian alimentation to a carnivorous one; the muscle becomes stronger.

The sexual maturity is achieved in a span of time varying from species to species, but the growing period does not end with it: the individuals in advanced age reach bigger sizes than the juvenile ones.

All the complex processes at the base of the described metamorphose need thyroid hormones, the absence of which will stop the development.

Let us now examine the ecology and the zoogeography, in general terms, of the members of this order. The Anura , much more than any other species of vertebrates, are subject to environmental influences and to the health status of the biotope where they are, and act as real and proper biologic indicators.

As a matter of fact, they can regulate their body temperature in respect to the environmental one, in a much more limited way than the reptilians. If during the migration to the place where to lay the eggs the temperatures decreases of 5° C, the Common Toad (Bufo bufo) hides underground. If a frog is at a temperature under the 10° C, whatever hungry, it will be unable to nourish.

Development and metamorphose of the Red Frog (Rana temporaria). Eggs with developing embryos and just born tadpoles. Note the cord and the outer gills. Tadpoles with outline of back limbs. A tadpole with well developped fore and back limbs, and just metamorphosed with tail residue. Adult specimen © Giuseppe Mazza

Another environmental factor which influences fundamentally the life of the Anura, is the humidity of the air. The body of these animals, as we well know, is covered only by the skin; it is not protected by any other auxiliary defensive apparatus, such as hairs, scales or flakes. It is therefore evident how the body fluids are easily subjected to evaporation. The limits of loss of weight caused by the evaporation born by the anurans vary depending on the species. Some species living in dry soils may bear evaporations up to the 50% of their own weight. Others, on the contrary, do not bear evaporations of more than the 30%. The dryness of the air strongly affects the social life of the Anura.

Bufo retiformis in Sonora Desert. Anurans may adapt to extreme environment conditions © G. Mazza

In conditions of extreme drought, they do not nourish and, even if being ready for the fecundation, they do not mate.

In spite of this strict dependence of the Anura from the environmental conditions, these amphibians populate regions and places which would seem unthinkable due to the extreme local conditions and their heavy subjection to them.

The zoologist biologists have discovered anurans in the waters of the semi-desert regions, in the sub-equatorial regions; these amphibians get even the extreme North, reaching mountain areas up to 3.000 metres of altitude.

The Anura are animals with a mainly nocturnal life, even if there are exceptions like the tree frog, which does not burrow during the day. The young of some species, like those of the Bufo bufo, have diurnal habits and only when adult will pass to the nocturnal life.

The salt concentration of the waters where they effect all or part of their vital cycle is important for the transition from the larval to the adult status, as well as for the adult animal itself. In this regard, we notice that usually the amphibians have adapted to salt concentrations typical of the fresh waters.

Also this rule, as usual, has an exception: the Crab-eating Frog (Rana cancrivora), lies the eggs in the dens of the crabs, in the intertidal zones or close to the Mangrove associations, where the salt concentration of the water is just a little lower than the sea.

The alimentary function is strictly related to the remarkable sensorial capacities (vision, hearing and smell) these animals have. Thanks to their good smell, they can get the smell of the Common Earthworms, wandering oligochaetes (Lumbricus terrestris), but they get ready to catch them only if the see their movement. Experiments in this regard have been carried, from which it results that these animals are not interested in their usual preys if these keep still, and jump to capture of small coloured moving objects.

Anurans are mostly night animals, but Bufo bufo young are active by day © Giuseppe Mazza

Due to the extreme mobility of their eyes, their visual field is very vast. Once the prey is sighted, they effect a rotation of the head in such a way to place it in line with the prey, and evert rapidly the tongue for catching it the viscous liquid which covers it.

If the morsel is small, it is quickly swallowed. If, on the contrary, it’s a prey of a good-sized prey, then this is caught with the jaws and sometimes pushed into the mouth with the help of the forelegs.

Once the meal completed, the same legs are utilized for cleaning up the mouth from eventual particles of detritus.

The alimentation of the adults is mainly carnivorous, as they normally eat insects and other invertebrates. Nevertheless, even if not frequently, they may eat small vertebrates, such as mice, small fishes (gambusias), etc.

Usually, there are no particular alimentary exigencies: the choice of the food depends also on the availability in loco. As it happens for the earthworms, also these amphibians may swallow big quantities of mud rich in micro-fauna.

These animals are able to learn things from the previous negative experiences. As a matter of fact, once “tasted” bees and wasps, which have an unpleasant flavour, they are carefully watching not to eat them again.

Phenomena of cannibalism are not so rare, between individuals of the same species as well as between individuals of similar species. Different are, depending on the locations, the natural foes of the Anura: usually it’s matter of birds, for which in any case these amphibians do not represent a particularly good choice. Other predators are carnivorous mammals, such as foxes, weasels, raccoons, etc.

Generally, the toads are less sought for than the frogs due to the poisonous substances contained in their skin and also because not edible. The eggs and the tadpoles are more subjected to destruction than the adults, reason for which the quantity of eggs laid at each deposition is very big.

Vigilant eye of Bufo bufo. Anurans have a very wide field of view © Giuseppe Mazza

There are many animals which love to eat the broods: salamanders, ducks, ringed snakes, mallards, swans, fishes, larvae of carnivorous insects (e.g. dragonfly), etc.

A fundamental characteristic in the social life of the Anura Anura is the emission of sounds by means of the vocal organ of which we have already briefly treated. These sounds have different timbre and intensity depending on the species as well as on the type of communication.

By the time of the coupling, a huge number of males unite in shouting calls. In this case, the shouts work as sexual attractors for the females of the same species, even if these choirs are often formed by individuals of different species, evidencing discriminatory capacities.

In some species, the female is active in the choice of the partner and at times replies to the call.

Besides the love calls, there are also other types of sounds, like, for instance, the shouts emitted for frightening the other competing males, or the warning cries produced, both the mouth wide open, unlike the love call songs which are produced the mouth shut.

In the Zoological scale the Anura are the first vertebrates to produce the sound and the acoustic comprehension in “social” function. The diversity of the sounds is another standard of classification utilized by the ethologist biologists which has permitted the differentiation of several species.

Similarly to other types of animals, also the anurans are subject to moulting. For instance, in summer the toads change the skin by two weeks intervals. When the time of the moulting approaches, a mucous substance is emitted under the old skin in order to facilitate the detachment of the same. The breakage of the old skin happens following prefixed procedures. The animal helps with the legs and, after having taken off the skin from the whole body, swallows it, beginning with that located around the mouth.

Bufo calamita. Toads are less endangered than frogs due to the poisonous skin and inedible flesh © Mazza

In the winter time, or in the drought periods, these amphibians fall in a deep “lethargy”, during which they do not react to any environmental stimulus, however strong this may be. This lethargy is not to be mistaken with the normal rest, during which the animal is very vigilant and attentive.

As written before, the anurans are spread all over the Earth, but the Arctic and Antarctic zones and few other Oceanic islands. The 80% of the species is concentrated in the warm and very humid tropical regions.

Some species are naturally endangered, others, on the contrary, are threatened by the massive done since the sixties up to now of the DDT in agriculture and by the utilization of other pesticides, insecticides, herbicides and fungicides.

Finally, the nowadays clear “pandemic” distortion done by the human being of the climate and of the “biosphere” and consequently of the global ecologic balance, by means of the planetary pollution, is increasingly cause of the loss of tens and tens of species each year.

It is possible that some viral and protozoan forms of bacteria may be also the cause, not yet discovered, of the decimation of some species in the tropical environments.

The IUCN, the CITES, the Wwf monitor the density of the natural population, realizing, if necessary, programmes of Taxon Advisory Group (TAG) and forbidding their trade with strict laws, at least for the species belonging to the “Red list” of the IUCN, as considered as “endangered species”.