All you want to know about aloe, from historical, geographical, growing and medicinal points of view. Although the Aloe is a member of the Lily family, it is very cactus-like in its characteristics.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

In July-August, in full austral wintertime, it is difficult to find more beautiful and unusual landscapes than a wavy savannah with thickets of aloes in full bloom.

They never grow up alone, and they stand above, with showy inflorescences, the low shrubs and the lean acacias of the South African “bush”.

At daybreak, before the increase of the temperature, and the awakening of the bees with their terrible stings, they are the compulsory destination of many-coloured pollinating birds.

In acrobatic positions, head down, they look for the nectar between the entangled corollas of the Aloe chabaudii, the waving inflorescences of the Aloe petricola and the Aloe castanea, and the huge flowered chandeliers of the Aloe rupestris, the Aloe excelsa, or the Aloe marlothii.

The lions have been turning around them for the whole night, and now it’s the turn of the shy gazelles, the wart-hogs, and the giraffe, which look, curious, at these odd “bunch of flowers”, at their height.

Images with warm colours, so much different from the conventional Africa that we know.

South of Namibia, in Namaqualand, the landscape changes all at once.

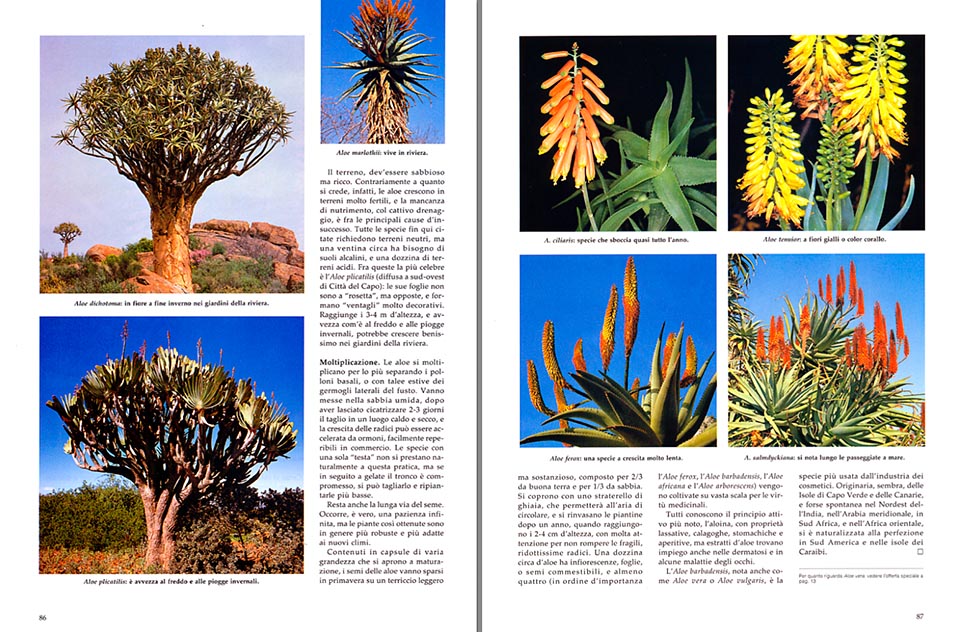

Desert for 9 months per year, it transforms, in August, in a huge garden: a sea of flowers from which emerge, majestic, on the big rocks, two gigantic arboreous aloes with golden corollas: the Aloe dichotoma and the Aloe pillansii.

When young, the stalk of this species is straight and smooth like a column, but, later, it ramifies and can reach the 10 metres of height, and 2 metres of diameter.

But, what is, botanically, an Aloe?

Even if, at sight, it doesn’t look so, it’s a Liliaceous.

The flowers, gathered together by hundreds of inflorescences, with the shape of a spike, reflect fully, in fact, the golden rules of the family: a cylindrical perigyny formed of six parts, six stamens and an ovary.

“Lilies not conforming with the rules”, then, which instead of taking shelter under the ground, in a bulb, to spend in lethargy the hostile months, they accumulate the water in fleshy leaves, disposed like a rosette, able to swell and deflate like an accordion, in order to cope with the long months of drought.

An original solution, for plants often of big size, obliged to have to do with sporadic rains, and summer temperatures which are close to the 45 °C.

But, how many are they?

It’s difficult to say, also because in nature aloes interbreed easily.

Time ago, they were talking of more than 1.000 species; nowadays, after having discovered at least 300 natural hybrids, botanists have agreed on about 200 species, for the 90% South African, with some specimens in Madagascar, in the remainder of Africa, and in Southern Arabia; and they think that the spontaneous plants out of above areas, have been, mostly, introduced by man.

In the ancient times, the interest for aloes was enormous.

Known to the Greeks for their digestive and laxative qualities (it seems that their name comes from “als” or “alos”, that is, “salt”, with reference to the bitter juice which is obtained from the leaves), the spread rapidly in India and in the Mediterranean area, thanks to the Phoenicians, adapting so well, to appear often autocthonous.

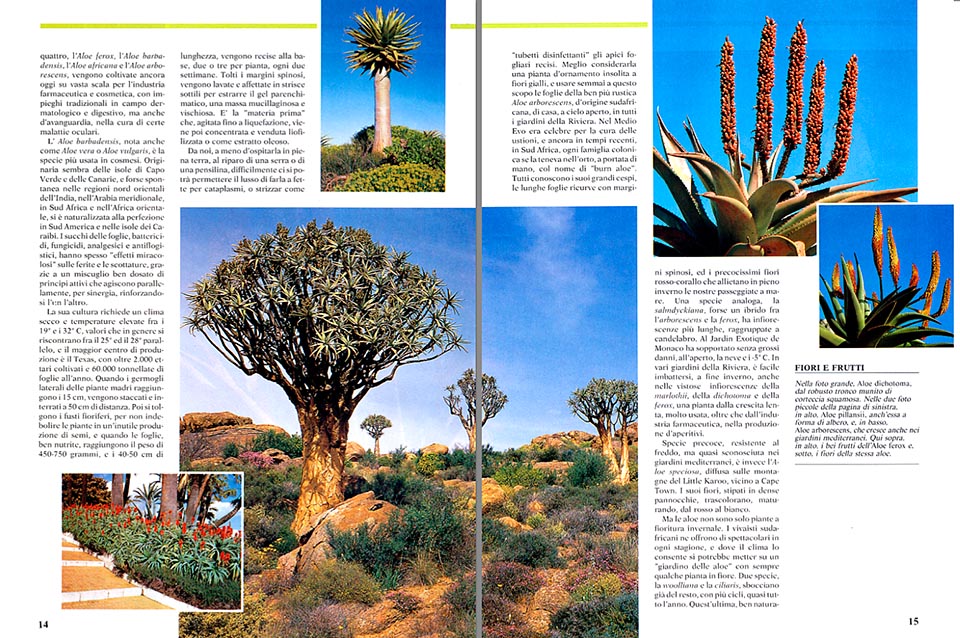

At least a dozen of species has edible inflorescences, leaves or seeds, and four, the Aloe ferox, the Aloe barbadensis, the Aloe africana, and the Aloe arborescens, are still cultivated on a wide scale for the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries, with employments, traditional in the dermatological and digestive fields, but also in new ones, such as in the treatments of some ocular diseases.

The Aloe barbadensis, known also as Aloe vera, or Aloe vulgaris, is the species most used in cosmetic.

Native, it seems, to Cape Verde Islands and Canaries, and perhaps, spontaneous in the north-eastern regions of India, Southern Arabia, in South Africa, and in East Africa, it has perfectly naturalized in South America and in the Caribbean islands.

The juices of the leaves, bactericidal, fungicidal, analgesic and antiphlogistic, have often “miraculous effect”, on wounds and burns, thanks to a well dosed mixture of active principles which act, on parallel lines, per synergism, both growing stronger.

Its cultivation needs a dry climate and temperatures between 19 and 32 °C, values that, normally, are found between the 25th and 28th parallels, and the major producer is Texas, with more than 2.000 cultivated hectares, and 60.000 tons of leaves each year.

When the lateral buds of the mother plants reach the 15 cm., they are taken off and interred at a distance of 50 cm. Then, the flowering stems are removed, in order not to weaken the plants with a useless production of seeds, and when the leaves, well nourished, reach the weight of 450-750 grams, and the 40-50 centimetres of length, they are cut at the basis, two or three for each plant, every two weeks.

Taken off the thorny edges, they are washed and sliced in thin strips, to extract the parenchymatous gel, a mucilaginous and glutinous mass.

It’s the “raw material”, which, shaken till it liquefies, is then concentrated, and sold, frozen dried, or as oily essence.

In our country, unless to keep it in open land, sheltered by a greenhouse or a pent-house, it will be almost impossible for us to cut it in slices for plasters or to squeeze, like “disinfecting small tubes”, the foliar summits previously cut.

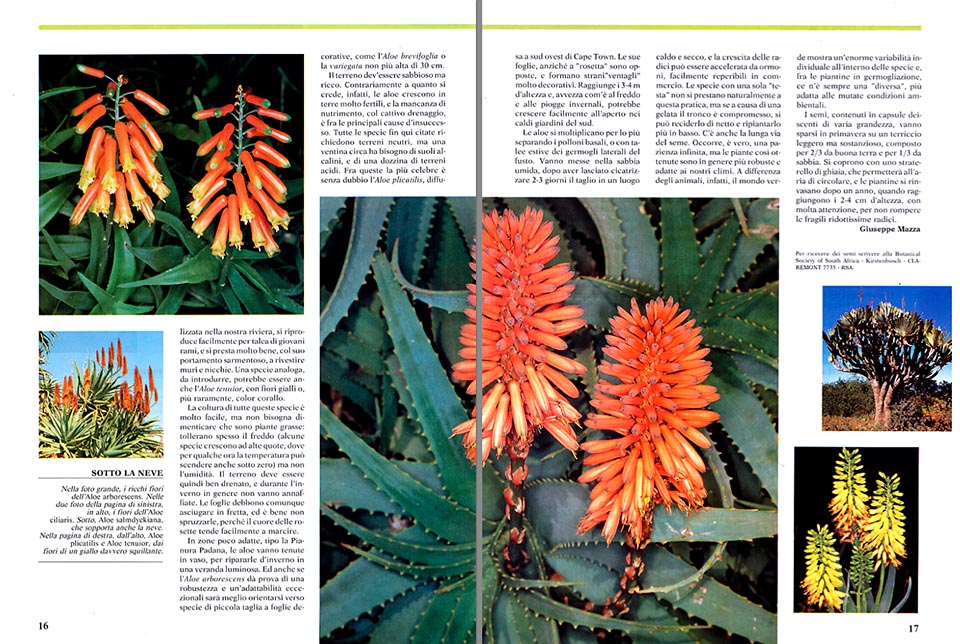

Better to consider it as an odd yellow-flowered ornamental plant, and use, for this purpose, if necessary, the leaves of the more rustic Aloe arborescens, of South African origin, common, in open air, in all gardens of the Riviera.

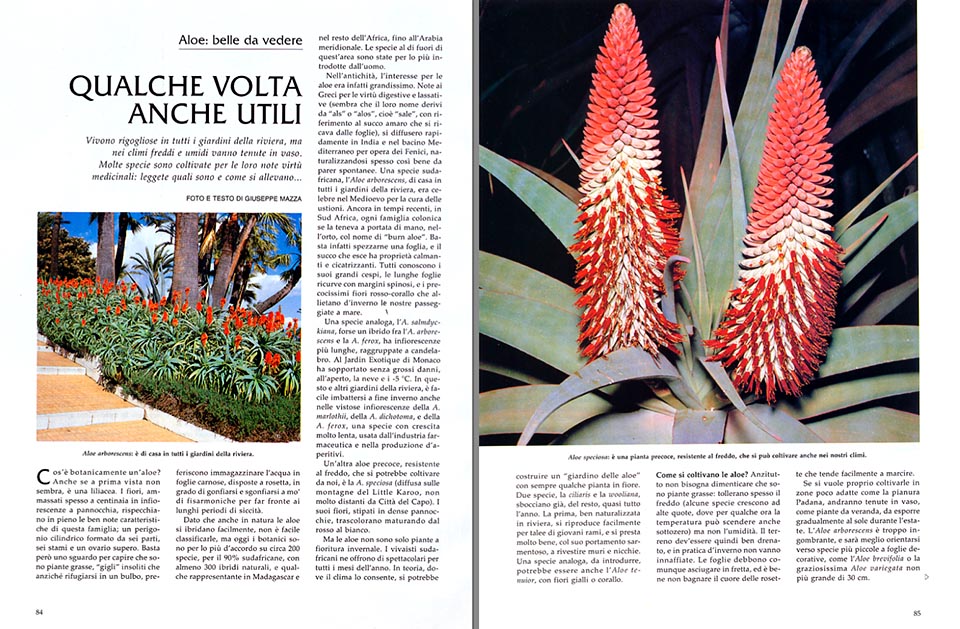

In the Middle Age, it was renowned for treating the burnings, and yet, in recent times, in South Africa, every family of farmers was keeping handy a plant of this in the orchard, and they called it “burn aloe”. Everyone knows its huge tufts, the long curved leaves with thorny borders, and the very early coral-red flowers which enliven in full winter our promenades along the sea.

A similar species, the Aloe salmdyckiana, perhaps a hybrid between the Aloe arborescens and the Aloe ferox, has longer inflorescences, tied up together, like a chandelier.

In the Exotic Garden of Monaco, it has endured without big damages, in the open air, the snow and the -5 °C. In several gardens of the Riviera, it’s easy to come across, by the end of winter, also the showy inflorescences of the Aloe marlothii, of the Aloe dichotoma, and the Aloe ferox, a slow growing plant, very much utilized, beyond the pharmaceutical industry, also in the production of appetizers.

Early species, cold-proof, but almost unknown in the Mediterranean gardens, is, on the contrary, the Aloe speciosa, common on the mountains of the Little Karoo, not too much far from Cape Town.

Its flowers, crowded in thick spikes, change of colour from red to white, when ripening.

But the aloes are not only winter-blooming plants. The South African keepers of plant nurseries offer spectacular ones in every time of the year, and where the climate permits, we might organize a “garden of aloes”, with always some blooming plants.

Two species, the Aloe woolliana and the Aloe ciliaris, blossom, however, with several cycles, almost all the year round.

The last one, well naturalized in the Riviera, reproduces easily by cutting of young branches, and is quite suitable, with its vine-shoot attitude, for covering walls and niches.

A similar species, to be introduced, might be also the Aloe tenuior, with yellow, or, more rarely, coral-red, flowers.

The cultivation of all these species, is very easy, but we have to keep in mind that they are fleshy-leaved plants: they often bear the cold (some species grow up in altitude, where for some hours the temperature can drop under zero), but they do not bear humidity.

The ground must be, therefore, well drained, and, usually, during winter time, they are not to be watered. The leaves, in case, must dry up quickly, and it is good not to sprinkle them, because the heart of the rosette has the tendency to decompose.

In less suitable areas, like the Po Valley, the aloes must be kept in pot, to shelter them, in winter, in a luminous veranda.

And even if the Aloe arborescens proves to be exceptionally robust and adaptable, it will be wiser to choose species of small size, with ornamental leaves, like the Aloe brevifolia or the Aloe variegata, not higher than 30 cm.

The soil must be sandy, but rich. Contrary to what is thought, in fact, the aloes grow in very fertile lands, and the lack of nourishment, along with a bad drainage, is among the main causes of failure.

All the species till now cited, need basic soils, but about twenty of them need alkaline ones, and a dozen need acid ones. Between these last, the most known is, without any doubt, the Aloe plicatilis, spread south-west of Cape Town.

Its leaves, instead of having a “rosette” disposition, are opposite, and so they form strange, very ornamental “fans”. It reaches a height of 3-4 metres, and, being used to the cold weather and to the winter rains, could easily grow up in open air and in the warm gardens of the south.

The aloes multiply, mainly, separating the basal shoots, or, otherwise, with summer cuttings of the lateral buds of the stalk. They must be interred in wet sand, after having left the cut haling for 2-3 days in a dry and warm place, and the growth of the roots can be sped up with hormones, easily found on the market.

The species with only one “head”, are, of course, not good for this practice, but, if owing to icy weather, the trunk is compromised, then it can be cut off, and replanted lower.

There is also the long way of the seeds.

An unlimited patience is required, this is true, but the plants gotten in this way, are usually more robust and suitable for our climates. Unlike animals, in fact, the green world displays an enormous individual variability inside the species themselves, and between the germinating plants, there is always one of them “different”, more suitable to the changed habitat conditions.

The seeds, contained in dehiscent capsules, of different sizes, must be disseminated during spring time in a light, but nourishing, mould, composed for 2/3 of good soil, and for 1/3 of sand. Then, they must be covered with a layer of gravel, which will permit the air to circulate, and the small plants are to be placed in other pots after one year, when they reach the 2-4 cm of height, with a lot of care, not to break the fragile, very reduced roots.

GARDENIA + SCIENZA & VITA – 1988

Recently the genus Aloe has been assigned to the Xanthorrhoeaceae family.