Family : Ranunculaceae

Text © Prof. Giorgio Venturini

English translation by Mario Beltramini

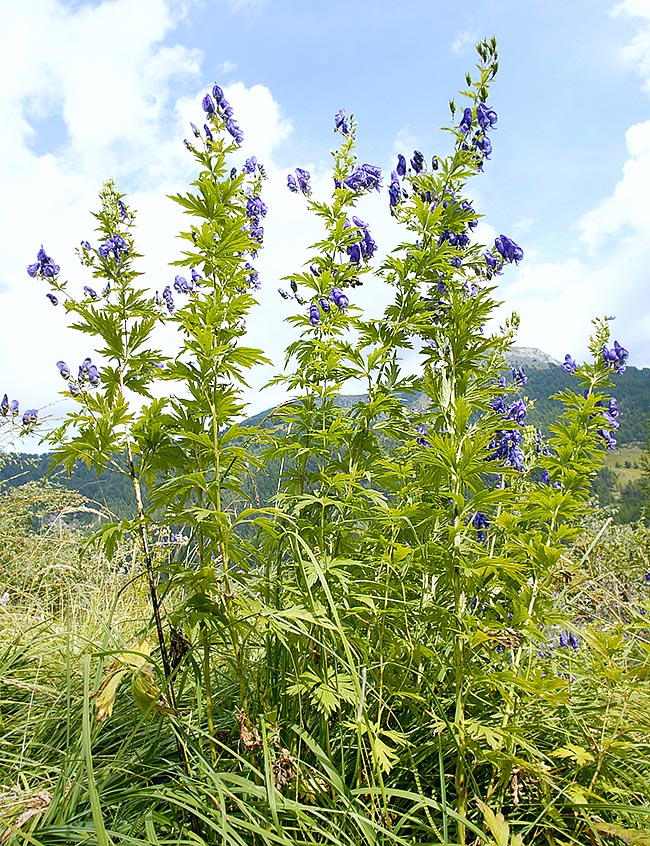

Aconitum variegatum is a typical species of temperate European reliefs, between 500 and 2000 m of altitude © G. Mazza

The genus, belonging to the family of the Ranunculaceae, is typical of the hilly and mountainous regions of the northern hemisphere. Most of the species are Asian, less numerous are the European species, few are the North-American ones.

The species of the genus Aconitum are often characterized by a great morphological variability, also due to frequent phenomena of hybridization and of polyploidy.

The variegated Monkshood, called also Devil’s helmet (Aconitum variegatum L. 1753) is a perennial herbaceous plant with erect stem; glabrous or pubescent in the upper part, 50 cm to 150-200 cm tall. The stem is usually ramified in the upper part. It is a rhizomatous geophyte: it is, therefore, a plant having an underground stem, the rhizome, which produces, every year, roots and aerial stems.

The dark green leaves do not have stipules and are spirally arranged along the stem. The basal leaves are glabrous, palmate, 10-20 cm broad, deeply divided in 5 segments, carried by an about 10 cm petiole. The veins are evident in the lower page. The leaves of the stem are smaller and the size is decreasing in the upper part of the stem.

The flowers, merged in paniculate inflorescences, zigzaggy ramified, are light blue or violet, with paler striations. The shape of the flower is characteristic, with five tepals, one of which, the upper one, forms a showy, very convex, compressed helmet; two sepals are arranged laterally and two, linear, below. The corolla is reduced and visible only after having moved the helmet, and shows two nectaria and six filamentous elements. The stamina are numerous and dark, spirally arranged and are present 3-5 carpels. The fruit is formed by 3-5 capsules which, when ripe, open releasing the seeds.

The pollination is entomophilous, mainly guaranteed by bees and wasps. In the ripe flower the helmet is often holed by the pollinating insects which forcedly open their way towards the nectaria. The plant reproduces also vegetatively by division of the rhizome.

Several insects nourish of the leaves of aconitum. Amongst these we remind various lepidopterans: Melanchra persicariae (Noctuid), Ectropis crepuscularia and Eupithecia absinthiata (Geometrids), and the Lymantriid Euproctis similis. Moreover, some hymenopters (Bumble bees) eat the flowers of various species of aconitum.

Distribution and habitat

Species typical of the reliefs of temperate Europe, in Italy is present in those of the northern regions, between the 500 and the 2000 m. The typical habitat is that of the humid clearings and of the undergrowths. The plant is protected. The subdivision of Aconitum variegatum in subspecies is presently subject to discussion.

The flowers, merged in paniculate inflorescences, zigzaggy ramified, are blue or violet, with paler streaks. Spirally arranged stamina. The fruits have 3-5 dehiscent capsules © G. Mazza

Numerous versions exist, since the old times, concerning the origin of the name “aconitum”. In Greek, with the name “akoniton (ακονιτον) was indicated a poisonous plant, probably, rightly, the aconitum. After some, the word should come from “akontion” (ακοντιον), which meant dart or javelin, in relation to the use done of the plant for poisoning the arrows. Others sustain a derivation from “konè” (konè), killing, or from the name of site, Acona, where the plant should have been abundantly present and where, after the myth, should have been located on of the entries to the Hades. We must also not forget that in Greek “aconitos” (ακονιτοσ) means also “without contrast, without fatigue” and after some this might be related to the anaesthetic and sedative properties of the plant.

The version certainly more suggestive and poetic is that reported by Ovid (Metamorphoses, book VII) who narrates how the deadly poison flower was born from the drops of the slime of the three-headed hellhound, Cerber, that Heracles did drag, chained drooling with hanger, out from the Hades. The name “aconitum”, after Ovid, should come from “akòne” (ακονη), stone, due to the rocky habitat. In the same piece Ovid relates how the witch and poisoner, Medea; had tried to kill Theseus rightly with a beverage based on aconitum.

Ovid. Metamorphoses book VII: “And here is that, after having pacified with his value the isthmus between the two seas, comes Theseus, still unknown to the father. To destroy him, Medea prepares with the aconitum she has taken with her from the lands of Scythia, a potion. This is a grass they say born from the teeth of the dog of Echidna. There is a cave whose entrance is hidden by the mist; from here, along a steep road, Heracles, the hero of Tiryns, dragged out, tight in chains of steel, Cerber, who jibbed and turned up its eyes as it did not bear the blinding rays of the sun: struggling like a fury for the rage, the monster filled up the sky with a triple bark, sprinkling the grass of the fields with whitish slime. And it is thought that this one, coagulating, found food in the fertility of the soil and became a poisonous grass, which arises, luxuriant, among the rocks, and for this is called aconitum by the countrymen.”

Also many of the aconitum vulgar names recall its toxicity: the English term wolfsbane comes from “wolf” and from “bane”, old English word meaning “death”, likewise one of the Greek names of the plant, “lycoctonos” (λυκοκτονος) meaning “killer of wolves”. On the same line are also the current English names “leopard’s bane” and “women’s bane”. Also the scientific names of other species of the genus Aconitum, such as Aconitum vulparia and Aconitum lycoctonum remind the toxicity and the use dome for poisoning harmful animals. In the Piedmontese dialect, the aconitum is called “ciancia d’osta” (gossip of the innkeeper lady) maybe in relation to the mental confusion, similar to the one given by the alcohol, caused by the toxin.

Other vulgar names recall, on the contrary, the typical helmet shape of the flower: besides the English “monkshood”, and the French “Casque-de-Jupiter”, we recall the Danish name “Troll helmet”, the “iron helmet”, the Norwegian “Odin’s hat”.

Pharmacological and toxic properties

Aconitum variegatum is one of the most toxic plants and this characteristic is shared by most of the species belonging to the genus. The main toxic principle is the aconitine, a neurotoxin blocking in opening position the sodium channels on the membranes of the nervous and muscular cells. Other toxins are the mesaconitin and the jesaconitin, similar to the aconitin.

In order to understand the action mechanism of the alkaloids of the aconitum we must mention the nature of the nerve impulses. Between the two sides of the membrane of the cells exists an electric potential difference, of the order of some tens of thousandths of a volt, due to an asymmetric distribution of ions. The nerve impulses consist in a fast and transitory variation of the membrane electric potential, caused by the transitory opening of channels permeable to the ions. Following the closure of the channels the potential resumes the starting values and the nervous cell is ready for producing a new impulse. The alkaloids of the aconitum link bind to the membrane ion channels and block them in open position, causing therefore a prolonged excitation and then inhibiting the production of new impulses.

The toxin is contained in all parts of the plant, being the highest concentration present in the rhizomes.

The stem, often ramified up, can be 2 m tall © Giuseppe Mazza

The aconitum is used in the eastern traditional medicine since yore, with the most different indications, often manipulated after recipes which should reduce its toxicity. In the Chinese traditional medicine the prevailing use is that as anti-inflammatory and as analgesic. The rhizomes were used in the Ayurvedic medicine for many ailments, after having submitted them to treatments able to reduce the dangerousness (the treatments foresaw the use of milk and urine of the holy cows).

Also the Greeks and Romans medicine foresaw the use of various species of aconitum. For external use it was applied as ointment for sciatica pains and for the rheumatisms. The applications for external use as analgesic, however dangerous, are justified by the fact that the aconitin is absorbed by the skin and acts directly on the nerves inhibiting the conduction of the pain impulses.

In Europe the aconitum is cultivated since very long time for medical use and in the past its extracts were imported from the East. Were used infusions and tinctures as sedative and analgesic especially for sciatica, tooth ache or the gout and its use has been suggested as sedative in the treatment of the laryngitis, heart palpitations, pneumonia, diphtheria and for asthma.

Due to the dangerousness (the efficacious therapeutic dose is very close to the toxic one), the modern western medicine has practically abandoned the use of this plant, replaced by less toxic and more efficacious substances.

The aconitum has been utilized as treatment of pneumonia and of diphtheria or of asthma, but especially as sedative for the heart palpitations. Actually, the administration, after a transitory acceleration, reduces the frequency of the heartbeat and the blood pressure. If the doses are high, we get to the cardiac arrest. The effects are due to an action on the nervous centres regulating the cardiac and respiratory activity as well as to a direct action on the cardiac muscle. As the aconitin inhibits also the activity of the sensitive nervous termination, it may carry out analgesic activity. For this action preparations based on aconitum are utilized in the traditional Chinese medicine as analgesic.

The rational utilization of the aconitum in medicine begins in 1763 by Anton Stoerck who proposed to use it for relieving the rheumatic and neuralgic pans. In 1845 Alexander Fleming described the toxic effects of the aconitin (the alkaloid characteristic of the aconitum), which avers fatal in dosages from 1 to 4 milligrams (in comparison, the deadly dose of the cyanide is of 150-300 milligrams). It initially excites and then paralyzes the nerve centres, the death occur from respiratory paralysis or cardiac arrest. For this reason it has been almost abandoned by the modern medicine, but in herbology it is still used for its analgesic, sedative and anti-neuralgic action, and is used for the local treatment of the trigeminal neuralgia. It is frequently used in homeopathy, especially for the treatment of the cooling diseases with fever, of neuralgia and of heart diseases.

Toxicology

The poisoning by aconitum is extremely serious and potentially fatal. The aconitum has on the nerves an initially excitatory action and later on inhibitory also by external application. The utmost caution is required also in the manipulation of parts of the plant. It affects the circulation, the respiration and the nervous system. It significantly slows the heartbeat and, in high dosages, the heart stops in diastole.

The prime targets of the aconitin are the cardiovascular system and the central nervous system and secondarily, the gastrointestinal tract, with manifestations including vomit and diarrhoea, ventricular arrhythmias, convulsions, cardiocirculatory collapse, respiratory paralysis. The first symptoms appear quickly, with numbness and tingling of the mouth and the tongue, salivation, nausea and vomiting; in the serious intoxications are prevailing the effects on the heart, which may last even for several days, the convulsions and sensory abnormalities. Impairments appear in the regulation of the body temperature. The bulbar centres may be initially excited and then inhibited. The action of the aconitin on the heart is a consequence initially of a stimulation of the cardio-inhibitory centre of the bulb and later on of a direct toxic action on the cardiac cells.

The corolla is reduced and visible only after moving the helmet, has two nectaria and six filamentous elements. Pollination is given to butterflies and hymenopterans © Venturini

Even the simple handling of the leaves may cause a poisoning through the skin, seen that the aconitin is easily absorbed by the same. In this case the gastrointestinal symptoms are missing and the first manifestations are tingling or numbness that, starting from the contact area, extend then to the arm and the shoulder before the cardiac symptoms do appear. The use of ointments is strongly discouraged, especially in case of presence of abrasions.

The treatment of the intoxications is only the symptomatic one; acting within an hour from the ingestion a gastrointestinal decontamination may be tried through the administration of activated carbon. Seen that the alkaloid is quickly eliminated, if the patient survives for 24 hours, generally the prognosis is good.

History and Magical uses

The aconitum was sacred to Hecate, the goddess of witchcraft, of the Hades and of magic, who, among other things, had used it for poisoning her father. In the old Greece, the aconitum was used for preparing poisoned baits for foxes and wolves (hence the Greek name “lykotonon = wolves killer). Much diffused was the use for poisoning spearheads and especially arrows.

In the mythology also Heracles did poison his infallible arrows with the aconitum (but also with the blood or the bile of the Hydra) and with a poisoned arrow did hit by mistake at a knee his mentor, the centaur Chiron, inflicting him a very painful and unhealable wound. Being immortal, Chiron did suffer for long time, till when Jupiter, moved to pity by the sufferings, granted him the death. It is said that in the Greek island of Kea the old people become a burden to the society were poisoned with a beverage made from aconitum. Dioscorides in his De materia medica and Theophrastus in the Historia plantarum did state that it had the power of paralysing a scorpion.

In the old Rome its cultivation was limited due to the wide use done of it as poison and the “Lex Cornelia de sicariis at veneficis”, law enacted by Sulla in 81 BC for fighting the crimes and the poisonings, made explicit reference to the aconitum. In the same years, the Bluebeard of old Rome, Calpurnius Bestia, shady character involved in the Catilinarian conspiracy, had used it for poisoning several of his wives. Pliny describes the plant in a very detailed way in his Naturalis historia and refers that “the barbarians hunt the panthers with meats rubbed with aconitum. Immediately, the pain takes their mouths and for this reason some call this poison strangler of panthers”. Then, curiously, adds “the beast cares with human excrements and is very greedy of these ones…”.

Ibn Wahshiyya, Iraqi alchemist, historian, agriculturalist and Egyptologist of the X century (had been able, among other things, to decipher partially the Egyptian hieroglyphs) wrote a book on the poisons, a real treatise of toxicology, where he amply relates about the aconitum.

In the past, diffused was the belief that a poison might be an antidote against another poison (still nowadays the homeopaths sustain a similar theory) and the aconitum, very strong poison, was considered as antidote against the most powerful poison, that of the scorpion (Ben Jonson, 1603, Sejanus). In the Middle Age to the whole Renaissance, the aconitum was used in the recipes of the European witchcraft as component of magic ointments and the herbaria of the yore treat amply about it. The aconitum was one of the poisons used trials by ordeal: in India those accused of crimes, invoking Brahma, submitted themselves to trials of administration of aconitum to prove their own innocence. In the Byzantine Empire the use of the poison was much diffused, also for killing the rulers (a widespread fashion in those times), and the aconitum was one of the most used substances.

In recent times, the inhabitants of Kodiak Island did hunt the sea lions with arrows empoisoned with aconitum, as well as those of the Aleutian Islands and of Kamchatka and the Ainu of Sakhalin and Japan did use Aconitum ferox and Aconitum japonicum for sea lions and for bears, then did cut off the flesh surrounding the poisoned wound. Analogous used were common in other eastern countries.

Among the magic uses we remind the utilization of the aconitum as defence against the vampires and the werewolves and in the consecration of the ritual daggers. The binding with Hecate renders the aconitum useful for the access to the afterlife world. By wearing a charm obtained wrapping the seeds of aconitum in a lizard skin we get the invisibility and also a snakeskin lace containing roots of aconitum renders invisible the property of a plant to grant invisibility to those wearing some parts of it is shared by other species, such as, for instance, the Edelweiss (Leontopodium nivale). A bag with aconitum flowers placed in the bed renders more intelligent. The aconitum did enter the composition of the ointments used by the witches, along with the belladonna, henbane and thorn apple as hallucinogen: under the action of the potion the witches dreamt of flying and of participating to the Sabbaths.

Decidedly poisonous, also to touch, is a protected species of which much has been said and written since yore © Giuseppe Mazza

In the Tantric rites the aconitum was consumed as a psycho-active drug allowing the contact with Shiva (Shiva was blue, having eaten the aconitum; therefore, by eating it, they got in touch with him). In some rituals it was smoked, but the use (with caution) was reserved only to the most experienced adept.

The use of the aconitum for criminal purposes goes on still now: one of the most famous cases has been that of the “curry murder” happened in England in 2009. A woman of Indian origin has been sentenced to jail because she had killed her lover with a curry kickshaw poisoned with aconitum. Numerous are the instances of accidental intoxications for ingestion of parts of the plant, mistaken for edible species or for a careless use for medical purposes.

Aconitum in literature

Also the literature has been attracted by this splendid plant and its toxicity has rendered it a symbol of evil, for instance, Virgil, to list the merits of Italy, tells us that here it’s always spring, the crops abound and is absent the aconitum which may mislead the herbs gatherers “nec miseros fallunt aconite legentes” (Georgics, book II).

The Greek poet Hedylos, to say of the inability of a physician, wrote that he was worse than the aconitum ‘the aconitum is nothing compared to this two-legged poison and the morticians should compensate him for all the work he gives to them”.

Tasso cites the aconitum in the creation of the toxic herbs in The seven days of the created world: “Hemlock was born along with grain; with the other foods appeared at once the hellebore, and the colour was white and black…Then the aconitum…’.

Shakespeare recalls the toxicity of the aconitum in Henry IV: “the unique cup of their blood, even if mixed with the poison of the calumnies that inevitably the times will pour there, never will crack, as much it operates with the strength of the aconitum or of gunpowder.”

Lord Arthur, the main character of “Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime” by Oscar Wiled, tries to poison with an aconitum bonbon his elderly relative Lady Clementina (who, conversely, dies a natural death before having tried the fatal bonbon).

Gabriele d’Annunzio, sensible to the beauty of the flower (but he did well know the tincture of aconitum as it used it for curing his terrible toothaches), writes in the Undulna: “Blue are the shades on the sea. Like sparse flowers of aconitum. Their tremor shakes the infinity to my astonished look”.

In the libretto of Macbeth by Verdi, Francesco Maria Piave associates two symbols of the poison: “you poisonous toad sucking the aconitum…” in the preparation of the witches’ hellish beverages.

Snynonym : Aconitum cammarum Jacq.

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within RANUNCULACEAE family please click here.