Text © DrSc Giuliano Russini – Biologist Zoologist

English translation by Mario Beltramini

The Paleontological origin of the two genera Loxodonta and Elephas

The roars emitted with the trunk are typical of every Loxodonta Africana © Mazza

Until a few years ago, it was thought that both Asiatic and African elephants were directly descending, talking in a paleontological way, from the Mammoths.

In particular, the palaeontologists thought that a common ancestor, the Archidiskodon, had generated both European and Asiatic Mammoths, in their turn progenitors of the genus Elephas, limited to the present Asiatic species, whilst the Palaeoloxodon, had to be the progenitor of the genus Loxodonta, of which, however, we cannot find still now any fossil remains.

But in 1995 some biologists discovered in Uganda fossils of an animal classified as Loxodonta adaurora, dated to 5,5-6 million of years ago, in the Quaternary Period, that comes from the progenitor of the Loxodonta, and therefore the hypothesis of the Palaeoloxodon is abandoned. Nowadays, the biologists experienced in palaeontology suppose that the family of the Elephantidae has had an independent evolution inside the order of the Proboscideans (Proboscidea).

After some biologists, this family is to be backed even to the genus (Moeritherium), with an unknown number of intermediate fossil forms, not yet discovered, which lived in the Oligocene epoch, therefore about 40 million of years before, in the Egyptian plains.

Lastly, historically talking, two species of Loxodonta, the Carthaginian Elephant (Loxodonta pharaoensis) and the African Pygmy Elephant (Loxodonta pumilio), have extinguished somewhat recently.

They should have disappeared between the first and second century A.D., but some biologists think that the origin of the Carthaginian Elephant should be Persian, whilst fossils found in the Congo River basin, from which they have speculated the existence of the Pygmy Elephant, should be ascribed to the African Forest Elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis), not completely developed. The origin of these animals is however still poor of fossils and is much controversial for the zoologist biologists and the palaeontologists.

The present elephants

The African Elephant (Loxodonta africana), the largest pachyderm, is also the heaviest and biggest placental, terrestrial, quadruped mammal in the planet. It is a eutherian mammal of enormous size, belonging to the order of the proboscidians (Proboscidea), family of the (Elephantidae). It was described for the first time by the English zoologist biologist and botanist John Edward Gray, in 1836.

The Asiatic corresponding, the Elephas maximus, of which we shall treat later on in this text, even if of enormous dimensions, is smaller for both sexes, with a rosier colouration of the thick skin and smaller tusks, which are missing in the females. Even if it keeps a certain grade of wildness, has a more docile character than the African species. As a matter of fact, if compared to this last, it has had historically a grater frequency of contact and of interaction with the human being (for instance, in India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Burma, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Ceylon, etc.) and in the cities or villages of these countries it is not rare to find them very close, like in the proximity of a gas station or on a road which passes through a stretch of tropical or pluvial jungle.

The Elephas maximus, more docile, is used to live with men. Here, it pulls trunks and the master floating house © G. Mazza

In occasion of many South Asia festivals, they are harnessed with spectacular costumes, like it is the case of the procession of Esala Perahera in Sri Lanka.

In these geographic zones, they are utilized also for performing heavy duties, like transporting tree trunks, and for exploring the virgin forest, also because they are the only animals which are not attacked by the tiger.

They are finally utilized for tourism, for allowing, like it happens in Europe with the horses and the asses, exotic rides inside the tropical forests and in the gardens, for memorable photos. The Loxodonta africana is, on the contrary, much more savage.

Little prone to the contact with the man, it badly tolerates same. It is not accustomed and addicted to his presence, and may charge him with enormous strength and ferocity if it feels menaced or if it sees him as a danger for its offspring. Together with the Hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius), the Lion (Panthera leo) and the African Buffalo (Syncerus caffer), it is one of the main causes of death, made by animals, in the populations of the African villages, not to forget the devastations of the cultivated fields they find along their way, or which they invade, looking for tubers, grass, plants and leaves.

For feeding, the Loxodonta africana devastates literally the savannah, until its teeth, completely consumed and therefore no more usable, condemn it to die for starvation.

No other animal so deeply affects the savannah and the landscape ecology of this biotope, as the African elephant.

Esala Perahera procession with harnessed Indian elephants in Sri Lanka © Giuseppe Mazza

Its huge appetite and its extraordinary strength have had remarkable effects on the vegetation and therefore on the habitat of the other animals which frequent the same areal.

By means of their long trunk, the Loxodonta africana pull off, for instance, whole branches of Acacia tortilis, so much that they are unable to grow up again. Moreover, with their huge head they push off whole trees, and the surviving trees are utilized for polishing their tusks, which are continuously growing incisors and for scratching. In this way, they get rid of the annoying pests that lurk in their thick skin, infesting them.

Obviously, as already mentioned for the hippopotami, the rhinos, the African buffaloes, the giraffes and other herbivores, also for the Loxodonta africana there is the cooperation with egrets and oxpeckers, for keeping under control the number of pests present on the surface of their body, such as ectoparasites which are, either encysted in the skin or also the ritual of diving and bathing in pools of mud, with which they sprinkle themselves completely with their trunk, for the same purpose and also for cooling up from the sultry temperatures of the savannah.

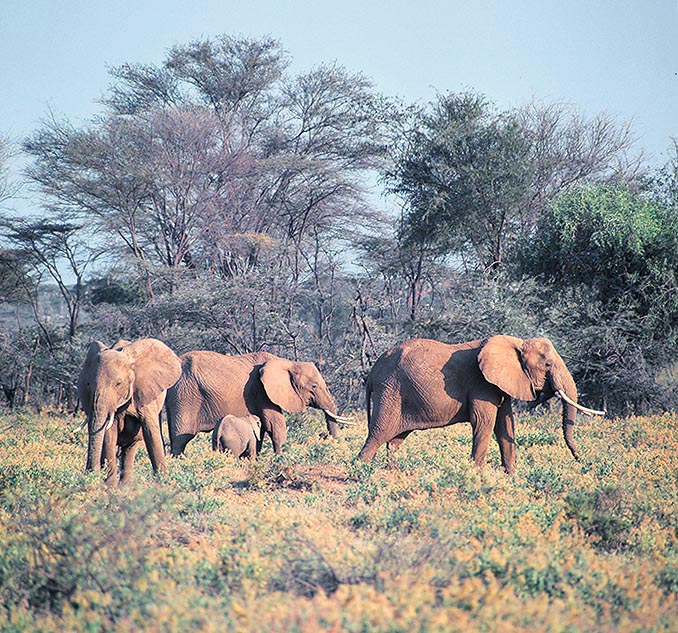

The African elephants live in groups, called also herds, formed by a certain number of sub-adults specimens, both males and females, of cubs, always strictly protected inside the herd, of two-three adult males, which may cooperate for the defence and of an equivalent number of adult females. Some of these are the mothers of the cubs, and one female, acting as matriarch, is often the leader and the dominant of the group. For this reason, it is said that the society of the Loxodonta africana has a “matriarchal organization”.

There is a dominating female, which decides when it’s time to go, in which direction to move, and who is to be sent away from the herd because it has not been observant to the internal rules of the group. This female intervenes also in the caring of the cubs, and is that which attacks the first for the defence of the group.

For eating, the Loxodonta Africana spoils its habitat, preferring the branches of the trees to the grass © Giuseppe Mazza

For instance, in the past, during the eighties, the zoologist biologist John Goddard, director and curator of the Serengeti and Ngorongoro Park, remarked that a cub of elephant was not breastfed by its mother, due to distraction, and was therefore under risk of dying for starvation.

The matriarch realized immediately what the problem was, and compelled, with powerful strokes of its trunk, the inhuman mother to nourish at once its cub. The herds of African elephants perform either daily transhumance looking for food and water, covering even distances of 50-70 km per day, or real “social migrations” of hundreds of kilometres, following the seasonal rhythms.

In the savannah they contribute to form what is called by the biologists a “community of herbivores”: the result of the sum of all the phytophagous populations present in such biotope.

The ecologic and eco-ethologic evolutions, the non-overlapping of the different alimentary ecologies, have permitted to a great and diversified number of herbivores to live in the savannahs and the plains avoiding any form of competition. From here has come, for the zoologist biologists, the concept of “biomass” which represents the total impact of the living organisms on a certain area of surface. This concept is quite useful for the zoologists and is more useful than the counting of the specimens present in that area for understanding the relations existing between the green plant, producers of “substance or organic mass”, and the primary consuming animals: the herbivores.

So an African elephant, of about 6 tons of weight, consumes 30 times more of food than an impala, which weighs 59 kg. The zoologist biologists of the Nairobi National Park, have for instance calculated that the present herbivores, African elephants included, form a biomass of 12,6 tons per square kilometre. But, in other zones, we can get to 18-20 tons per square kilometre, depending on the distribution of the animal species.

Like other herbivores, also here egrets and oxpeckers control the pests © Giuseppe Mazza

For the precision, an “animal community” is not only formed by herbivores: there are also the predating carnivores, secondary and tertiary consumers, and a multitude of invertebrates of the edaphic fauna, of insects, birds and reptilians.

The organic matter produced by the plants goes therefore through a complete succession of living forms, forming a “food chain”.

The carnivorous species control the demographic density and the multiplication of the herbivores (but elephants and rhinoceroses), whilst the herbivores influence the development of the vegetal species.

The result is a complex and frail ecologic balance, which only casual variations can temporarily break.

By the beginning of the dry season, the Loxodonta africana nourish of grasses along the lakes, which are reducing, and then go where the trophic resources and the water are more abundant.

The African elephants eat a great variety of vegetal food, from the grasses to the barks of the trunks and the foliage of the trees, which they reach, thanks their long proboscis, an organ which has become a real fifth limb, formed by the fusion of the nose with the upper lip: robust, long and muscled, so much to be able to eradicate a tree, provided with very sensitive prehensile and tactile skills.

In some American zoological gardens, they have been able to teach some African elephants how to use a brush for painting and these have created real animalistic masterpieces!

The trunks of the trees, downed also with the body, are then scraped and finally sentenced to the desiccation and death; the zones frequented by the elephants, often close to huge ponds, are at once recognized thanks to the presence of these dead trunks.

The mud baths cool the ideas and are good in fighting the pests © Giuseppe Mazza

In this way, due to the elephants, the jungle transforms in wooded savannah, and when the fires take place, this last will degrade to a grassy savannah.

But this process is not only destructive, because, in a certain way, the survival of certain species of animals is helped.

The uprooted trees and the broken branches that the Loxodonta africana leave by their passage, furnish in fact first choice easy nourishment for the other herbivores. And during the dry season, the wells they dig in the dry riverbeds looking for water, form water resources, useful to other mammals, birds and reptilians.

Lastly, digging with their feet and the trunk, the elephants often discover salt deposits, of which they are greedy, and useful to many species.

Some African elephants prefer woody habitats. And, owing to this geographic isolation, by means of an “allopatry” speciation, an independent species has come to life, the Loxodonta cyclotis .

The dimensions are always conspicuous, but inferior to those of the Loxodonta africana, that populates the woody and grassy savannah.

Due to the pitiless hunting to which have been subjected during the second half of the XIX century and during the XX one, up to the eighties, due to the ivory of the tusks and the stupid tourism of hunters seeking trophies, not to forget the sad phenomenon of the poaching, both the Loxodonta africana and the Loxodonta cyclotis, are by now reduced to the limit.

The African governments, in collaboration with the zoologist biologists both African and strangers of the IUCN, the CITES and the WWF, and the rangers of the foresters, have declared illegal, with strict and precise laws, the trade of the ivory and consequently the hunting of elephants, confining them, in the meantime, in “natural reserve parks”, where the only safaris allowed are the photographic ones.

The huge feet allow proceeding gently, with no traces on the compact ground © Giuseppe Mazza

In such contexts, being free to reproduce, their population in some periods has increased so quickly to deplete the natural resources of the region of confinement, rendering the same arid and obliging the biologists and the rangers to shift them to other zones.

Both Loxodonta africana and Loxodonta cyclotis are autochthonous of sub-Saharan Africa. Actually in the past the distribution of Loxodonta africana was so vast to cover the whole sub-Saharan Africa, whilst nowadays is much more reduced, and we find it only in the grassy and wooded savannahs of the centre-oriental and north-occidental part, between the 17th parallel North and the 17th South.

The Loxodonta cyclotis, at home in the forests and not in the savannah, has an ampler distribution covering almost all the sub-Saharan Africa.

Obviously, for both species, inside the “protected areas”. These two species of pachyderms may meet, but are not in competition for the food resources, and do not seem to cross sexually. Other specimens are spread all over the world, but the Poles, inside zoological gardens, zoo-parks, zoo-safaris, where, together with the Taxon Advisory Group (TAG), projects carried out in the African natural parks and reserves, from which are produced the guidelines for the proper management and the proper keeping of the “animal welfare”, are developed programmes of reproduction both natural and artificial of these splendid terrestrial giants, which will be useful to the zoologist biologists for keeping the population in the right balance.

In zoogeographic terms, indeed, also two races or subspecies of both African species exist. These races, which are the Loxodonta africana africana and the Loxodonta africana cyclotis, are intra-fertile inside their own groups, and may be inter-fecund between the two races, as they derive from the same species.

The herds, led by a female, are continuously moving, seeking water and food © Giuseppe Mazza

They have somatic differences in respect to the original species, but not so important and numerous to have them classified as distinct species; they have also the same distribution in the home ranges of the species from which they come.

The dimensions of these elephants, both the Loxodonta africana and the Loxodonta cyclotis, are really enormous.

As mentioned, the second species is smaller than the first; it has more rounded auricles and is lower at the withers than those of the savannah, is lighter and has thinner tusks.

In spite of the huge dimensions and the powerful mass which instils fear and respect to any other animal, they are however endowed of a remarkable agility and velocity; when running and charging they may reach the 20-25 km/h.

It is not simple, not even for an experienced biologist or an experienced native living in one of the local villages present in the home ranges where these animals are, to feel their presence. The Congo Pygmies which were hunting them until the seventies, as well as the Kenyan Dorobos (utilizing spears), were often caught by surprise and killed by this pachyderm, by crushing, during their hunting practices.

They can move silently, in the forest as well as in the bush of the savannah, without being noticed. This happens because the weight of the body is equally distributed on the columnar limbs and on the huge feet supporting them.

These characteristics of their limbs, so powerful and particular, which support weights reaching the 6,5-7 t, may become counterproductive when, for whatever reason, one of these giants breaks a femur or a humerus, when falling, for instance, from an unseen cliff, as their regenerative capacities are rather scarce.

In the dry season they dig in the dry riverbeds looking for water, good for many species © Giuseppe Mazza

When this happens, also in a zoo, it is practically impossible for the veterinarians to carry on surgery on them, and it is not even possible to build up orthopedic implants, as it is on the contrary possible on other animal species, for supporting them and guaranteeing an adequate form of walking.

They are, in fact, death sentenced, like the racehorses with an injured leg. In any case, the huge feet allow the animal to proceed prettily, with an almost graceful gait, contrary to what the common sense might lead to thing.

Even if weighing several tons, often they do not leave any trace of their passage on the firm soil, and for a zoologist biologist studying their habits, life and customs, it is not always so simple and easy to find them.

The Loxodonta africana has a massive head with great auricles, which are fluttered for the thermoregulation of the head as well as for communicating by means of codes formed by the number and frequency of the waftures. They are used for giving orders, threats and other forms of social interaction between conspecifics.

In the Loxodonta cyclotis the ratio between the volume of the head and the size of the ears is such to render them looking absolutely the largest, but in reality the dimensions are always in favour of the species living in the savannah.

The forehead is wide and convex upward. In the male of Loxodonta africana, it determines a convexity in the initial part of the proboscis, absent in the females. This is a character of sexual dimorphism, which can be identified by an experienced biologist even from far away when observing them with the binoculars, although the thing is not so simple.

With 9 litres sips each, an African elephant drinks 90 to 200 litres of water per day © Giuseppe Mazza

The robust and muscled proboscis with which they reach the branches and the more succulent buds on the tops of the trees, smartly pick up the fruits fallen on the ground and with which they tear off big tufts of grass, is also utilized for drinking.

Even if it has a good resistance to thirst, an elephant drinks an average of 90-100 litres of water per day. In the warmest periods it can reach even the 200 l, sucking up 9 l at a time.

On its extremity, the trunk, which can be 1,5 m long, is equipped with two digit form appendices, utilized also for fondling the cubs, utilizing processes of tactile socialization, or for hitting a fellow or a predator when the animal gets upset.

On the sides of the proboscis, which we have not to forget has originates from the fusion of the nose with the upper lip, are present two imposing tusks which, in the males of Loxodonta africana (in the females there may be specimens without tusks, but those of the African species are usually always equipped of them, unlike the Asian ones which never have them), may reach a length of three metres, weigh up to 50 kg each with a diameter, at the base, of 20-30 cm.

Made of ivory and covered by enamel, they have the tip always turned upward.

As we shall see, they are utilized for the fights for the defence of the territory or of a source of water, from rhinos or hippos which would like to take possession of the same, against a conspecific male, for the conquest of a female during the mating season, or against a predator, for defending the offspring, human being included.

A herd of Loxodonta Africana cyclotis meets a group of baboons by the edge of Marsabit forest © Giuseppe Mazza

The cubs of African elephants may be at times (and this applies also to sub-adult young specimens) a prey of male lions.

In the Asiatic ones the danger comes from the tigers. This happens especially when herds are in movement or in transhumance, looking for a source of water and of food, situations where, due to inadvertency, a cub may remain isolated and get lost.

It is not any more able to reach the moving nucleus and is therefore an easy prey of the felines.

When a male is present, or an adult female, the lions, even if in groups, will very rarely have the courage to attack, as they would be vanquished by the giant of the savannah.

When this has happened, as it was filmed during the sixties and seventies by the fauna biologist, DrSc John Goddard, in the Kenyan Serengeti Park, even the strongest felines have been always defeated.

The enormous dimensions of the Loxodonta africana, tell us that upon its birth, the cub weighs already 125-130 kg. After about one hour, it is already capable to stand up and walk by the mother. It will suckle utilizing the couple of pectoral mammary glands, as it is typical for all the cubs coming to life in open spaces, such as savannahs and prairies, where the predators are always lurking.

When completely developed, a big male may weigh 6,5-7 t, with a height of 3,8-4,5 m at the withers; enormous male specimens have been sighted measuring 5 m of height at the withers, per 7-7,5 t of weight. Undoubtedly, real colossi of the Nature! The cows may reach the 3,8-4 m at the withers and the 4-4,8 t of weight.

The grey, gigantic trunk lays on columnar limbs, followed by the enormous feet, with the fingers, both in the anterior and posterior paws, sheathed in a sort of elastic cloth. Each finger has a thick nail.

The Loxodonta Africana cyclotis has thinner tusks almost parallel to the proboscis which skims the soil © G. Mazza

The Loxodonta cyclotis, species, as already told, from genetic analysis has resulted as being different, has some distinct somatic characters: a male, on the average, weighs from 3,5 to 4 t, is 2,5 to 3 m tall at the withers, the ears are more roundish and have upper margins which cannot touch each other, contrary to the savannah species.

The tusks, which are thinner, have the tip pointing down, and are almost parallel to the proboscis, which almost touches the soil; whilst in Loxodonta africana they are quite often converging.

The smaller size allows the forest elephant to manage in the thick African tropical jungle and, like almost all other mammals living in the jungle and forests, carries on a more solitary life, living in group only during the reproduction period.

When the Loxodonta africana graze in places where the trees are not abundant, the grass may be form even the 90% of their nourishment, but in the wooded regions, they prefer branches, twigs and leaves. Most of the food ingested can be found almost intact in the faeces. This, however, is not sign of a functional insufficiency of the digestive apparatus, but it depends on the rapidity with which the enormous quantities of food transit through the bowel.

In such a way, only the most nutrient parts of the plants are kept, whilst the woody component; which cannot be digested, is quickly expelled. Usually, the African elephants are able to destroy more vegetation than what they eat. They tear off enormous tufts of grass with the roots, swallow earth rich of rock salt and chew hard dusty barks; all this deeply chafes their teeth.

The heavy chewing molars, which dimensions have the size of a 2 years old infant’s clenched fist, do fall piece by piece as they get consumed, and are renewed six times during the life. When, finally, also the teeth of the last change (polyphyodont species) are consumed, the African elephant cannot anymore chew the food and is sentenced to death.

Pack leader of Loxodonta Africana cyclotis which, by chance, did not charge our stranded jeep © Giuseppe Mazza

The old males (this real cult of the death, particular characteristic of these animals, will be described later on in this text), often spend alone the last years of their life, close to the rivers, where the growing vegetation is more tender and richer of water, and therefore easier to be chewed without teeth or to be swallowed as it is..

Their odontogenesis (growth and replacement of the teeth), has a particular “kinetics” of growth and fall. We can say that at the birth the crown of the molar teeth is covered by cement, which is consumed quickly, showing the ivory and the underlying enamel.

The enamel is harder than the ivory and wears out more slowly, forming crests suited for crushing the buds, the branches, the bark and what else vegetal.

During all their life, the Loxodonta africana and the Loxodonta cyclotis use 24 molars, six for each half-jaw, but usually only two of them are used at the same time.

The teeth are formed by more laminas. As it gets consumed, the teeth advance in the jaw, whilst the laminas, gradually torn out, fall one after the other.

The following lines show the substitution sequence of the teeth (kinetics), on each side of the jaw, in the various stages of the elephant life.

The molars called 1-2, present from the birth, are covered by cement. When they are working (mastication), at this same time takes form the beginning of the molar 3, after them. When the molars 1-2 have disappeared, because fallen, the molar 3 becomes operational, advancing its position. As it wears out, the molar 4 takes form, same posterior position, and when the 3 is almost completely worn and is about to fall, the 4 starts working, moving slowly ahead. The kinetics of the teeth develops then the molar 5, as beginning, which, later on, will replace, once the development completed, the worn out number 4, which will fall in turn as no more useful for shredding and chewing.

In case of danger all the adults form a barrier protecting the cubs at the centre of the herd © Giuseppe Mazza

When the molar 5 is fully opera- tional, the number 6 begins to form, always back to the one working. Once the 5 fallen, the molar 6 becomes fully working advancing in the jaw.

Once this point is reached, and the molar 6 is worn-consumed and does not work any more, it falls but is not replaced by any other molar, because no other one has previously begun to develop, in a background position.

It is not clear if this discontinuance of renewal is in function of the age of the animal, for which reason the plastic phenotypic and regenerative capacities have decreased until they have stopped or if the above explained kinetics follows a rigid and fix genetic programme.

Furthermore, the African elephant, like many other big mammals, has a low coefficient of thermal dispersion.

As per the eco-geographic Allen-Bergmann’s Rule, the organisms with a smaller mass have a greater surface of thermal dispersion, contrarily to those having a major mass.

And whilst the appendices (ears, muzzle, etc.) of animals living in cold bio-geographic realms (like, in the northern part of the boreal hemisphere or at the extreme South of the austral one) are reduced in order to lose less heat, those of the animals living in the equatorial and tropical belts have bigger sizes in order to increase the coefficient of thermal dispersion.

For such reason, the African elephants have, in both species and relevant races, these huge auricular pinnae, fluttered continuously. Another means they utilize for fighting the temperatures which may reach the 50° C in the shade, consists in covering themselves, head and body, with a layer of humid mud.

Lastly, a further sophisticated means for fighting the heat is guaranteed by an intricate system of blood vessels which invade the huge ears, long up to 1,80 m and 1,50 broad. When they are waved, the blood flowing inside is cooled of five degrees and, seen that then it reaches the head, also the encephalon takes benefit of this.

Just born, a cub weighs 125-130 kg, and after an hour is already able to walk by the mother © Giuseppe Mazza

This system of blood vessels consists in veins which wrap the auricular arteries.

When the body temperature increases, also the blood pressure which pushes the blood in the auricles does the same.

In this area the arteries, expanding for the heat, give away part of the heat carried by the flowing blood, through a mechanism similar to a “counter-flow heat exchanger”, to the blood flowing into the veins wrapping them, which, being located in surface, dissipate it outwards.

The mechanism of the “counter-flow heat exchanger” is also utilized by the dolphins, at the level of the pectoral fins to avoid, during the intense physical activity, the over-heating of the limbs.

And when they have to effect some analysis, the zoologist biologists make the blood tests on the elephants rightly from these auricular blood vessels.

During the first seven years of life, the Loxodonta africana of both sexes develop with the same rate; when seven years old, they weigh 1-1,5 t. Later on, the males get the so-called “growth spurt”, growing up much more quickly than the females, so that a 50 years old male may reach the 6,5-7 t, against the 4-4,8 t of a female of the same age.

The growth is continuous and never stops. Theoretically, if they were able to live indefinitely, the elephants would grow without limits in height and breadth. In this respect, the biologists have noted that a 40 year old female reaches the 3,5-4 m at the withers, whilst a 1 year old female can pass under the legs of the mother, utilizing them often as a shelter.

The males, usually, do not exceed the age of 50 years. The females may reach the 60, but they have sighted specimens of both sexes reaching the 70 years of life, real patriarchs and matriarchs of the savannah. The females reach the sexual maturity, usually, by the 10 years of life, the males do the same one or two years later.

A cub shelters in its mother shade. The elephants suffer more the heat than the cold © Giuseppe Mazza

Nowadays, many groups live in precarious conditions due to the scarcity of food, for the overcrowding and the lack of shade (even if they live in a warm biotope, the elephants stand the cold better than the heat) in the reserves where they live, always smaller due to the mining activities and agricultural exploitation.

Due to these ecological stresses, the body development is affected and gets delayed. In some regions, the females are not fertile till the 18 years of age, and between one birth and the following one, even 8 years may pass, whilst, physiologically, only 4 should be needed.

The males of Loxodonta africana do not court the females before mating, but may fight against conspecifics of the same sex for their possession.

The females are in oestrum for 1-2 days and during this period they may mate with one or more males (polygamic species).

The gestation has an average length of 660 days (little less than two years).

After the delivery (always and only single, the twins are extremely rare), the females are again in oestrum two years later, but they go on in nursing the cub also during the following gestation, that is, up to the third-fourth year of life. As said before, the Loxodonta africana has a social organization of “matriarchal” type. More precisely, the basic unit is formed by an adult female accompanied by and offspring till the 14 years of age.

The adult males unite in groups or in unisexual pairs, but their solitary nature gets more evident with their ageing.

During the reproductive period, this cyclically happens every four years, the sexually mature females separate from the group followed by some males, which begin fighting with hard struggles, pushing each other with the muzzle and hitting with the tusks.

Time of feeding. The elephants’ milk is very rich in fats and proteins © Giuseppe Mazza

If the contenders belong to the same group, usually, the fights will end up soon, without any consequences..

If this is not the case, when one of the subjects does not belong to the group, the fights will become extremely ferocious, with deep wounds, and the death of one of the contenders is not so rare.

During the coupling the male leans with its forelimbs on the back of the female which, at this stage, must bear an enormous weight, while the vagina is penetrated several times by the huge penis.

This may cause serious accidents to the young female elephants, just sexually mature, but not yet completely physically developed.

It may happen that a male in heat, belong to a passing-by herd, tries the mating risking to break the back of an unlucky young female, if the members of the herd (the matriarch first), do not intervene to save it, sending away the intruder. These are real attempts of rape, as it has also observed in the orang-utans.

In the past, but often this happens also nowadays, the huge mass of the African elephant, its slow and unsure pace, and its apparent laziness, have led the inexperienced people to believe that it is a poorly intelligent and reactive animal.

But the zoologist biologists do not at all agree on this.

The high social organization characterizing the various nuclei or herds, the so much skilful use of the proboscis, the strong “homo-parental” mother-son and “allo-parental” conspecifics-cubs interactions, have clearly shown that this animal, besides having an encephalon of big dimensions, up to 5 kg of weight, is endowed of a practical psychic development.

As a matter of fact, although there is a neat division in family units (and in the older specimens there is also the tendency to live alone), in the points of water (ponds, lakes), often converge, at the same time, different herds of elephants, and those who know greet with the proboscis.

They have two udders and can nurse the cub also during the next pregnancy, till 3 years © Giuseppe Mazza

This is possible thanks to the proverbial “memory” characterizing these pachyderms, and to the voice, that is the “roars” emitted with the trunk, a sort of gurgles produced by the larynx, which are specific of each individual and are recognized by the conspecifics of other herds.

They can hear them even at kilometres far away, as, together with the smell, the hearing is perhaps the most developed sense of these animals.

Following the identification of this friend, the real greeting begins, which takes place with the contact of the trunks and the mouths, crossing the tusks: a real “Hello, my friend, how are you? How’s the life? It’s long time we didn’t meet”.

At the same time, with this ritual greeting, the specimens may smell the secretion of the reciprocal “temporal smelling glands”, exchanging in this way also an olfactory signal as well as tactile, from which they perceive, probably, also the health status of the friend.

We have recently briefly talked of the proverbial “memory” of the Loxodonta africana.

Actually, experiments carried on the field and in controlled habitat (zoological gardens, zoo-safaris, zoo-parks), of eco-physiology and eco-ethology, for the study of the mnemonic capacities (of memory) on these animals, have led the zoologist biologists and ethologists to get convinced that they have a “really developed” one.

For instance, these animals are capable to remember, even after many years, and without having gone back there frequently, the location of the water reserves in the arid habitat where they live.

This capacity is precious mainly in the periods of major drought, when the possibility of survival of a herd depends on the water supply.

The whole herd cares the cubs, fed and helped in the first life difficulties, such as crossing a river © Giuseppe Mazza

The females seem to have greater memory capacities than the males, and this maybe is another factor to their advantage which renders them team leaders.

Before treating of the particular characteristic of the “death cult or funerary”, as the biologists have called it, typical of these animals, especially of the African elephant, we have still to look at the “family life” which characterizes the Loxodonta africana.

We have affirmed before that the mother, actually, is not the only one to care the cubs, even if the homo-parental cares are in any case developed.

The whole herd feels responsible for the cares, the nourishment and the defence of the new born, which are helped in overcoming the initial difficulties of the life, which are not minor, like the crossing of a river, or the daily search for food, once weaned.

Although the nursing should last 3-4 months, often it can exceed the 2-3 years, reaching the four, but already some weeks after the birth, the cubs are able, between one feeding and the other, to eat solid food, in particular grass, which all the members of the herd provide to pick up, clean and crumble for facilitating the cub its assumption.

At times, the cubs are allowed to “steal” the food, partly chewed, in the mouth of an adult, mother or not. Real “nurseries” may be formed, where the females of the group take care of the cubs, whilst the mothers are busy in looking for the food.

The nurse in charge keeps the young under control, avoiding that they get far away. It controls their sleep, and furthermore chews their food which is then given them already “laboured”.

When, after long, two elephants meet, they greet and communicate by crossing tusks and trunks © Giuseppe Mazza

In case of danger, for instance the approaching of the lions, instead of running away, the adults take position to form a barrier, behind which are hidden the cubs that are to be protected.

If then, if unluckily happened in the past owing to stupid hunters, that a mother was killed, another female adopts the orphan cub, assuming the parental cares, between which the nursing, as it immediately becomes in condition to produce the milk.

The milk of this animal species is very rich in fats and proteins and is very dense and nutrient.

But one of the most mysterious and fascinating characteristics for the zoologist biologists, which is common in the African species of elephants (for the Asiatic ones we have not yet sure data about a similar phenomenon), is that of the “death cult or funerary”.

In fact, these animals show their intelligent and marked social sense also in the care of the sick or injured specimens of their herd. All the members of the group care the conspecific which is injured or sick even if condemned to death.

When a member of the herd dies, its body is covered roughly by branches, as if they were creating a grave. This happens before the arrival around the corpse of the scavengers like the vultures, for instance the Egyptian Vulture (Neophron percnopterus) and other species of vultures, or mammals like the Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta, in the past and still know called by some authors, Hyaena ridens), the Golden Jackals (Canis aureus) and other animals.

As soon as found a river, also the Indian elephant (Elephas maximus) can’t do without washing © Giuseppe Mazza

In the past, as shown in many movies, it was thought there were existing the famous “elephants’ cemeteries”, places impossible to find where the old specimens were going to die.

Actually, the presence of several skeletons in confined areas of Loxodonta africana and of Loxodonta cyclotis, would seem more logically ascribable to slaughter made by the human beings, for the ivory, or to sudden fires, burst in the savannahs, which have trapped by surprise more specimens at the same time, causing their death.

Let us treat now about the Asiatic Elephant, called also Indian (Elephas maximus) which lives in the jungle and the grassy plains of southern Asia.

The smaller size, 2,5 -3 m of height at the withers, with a maximum weight of 5 t, together with a profile of the convex forehead bound downwards, the absence of tusks in the females, which are smaller in the males, with smaller ears for both sexes and the extremity of the proboscis with only one digit form appendix instead of two, render it fairly distinguishable from the African Elephant (Loxodonta africana).

The Asiatic elephant is gregarious and forms groups of 20 or more individuals, which refer, also in this case, to the older female, charged to lead the group in the research of food and water. In its diet are vegetables of every type, from grass to bamboo roots, besides barks, fruits and twigs.

The quantity of food ingested daily exceeds the 50 kg and the look for food is interrupted only during the warmest hours, during which the animal rests and flutters continuously the ears for dispersing the excessive heat accumulated.

The Elephas maximus has a long history of life with the man © Giuseppe Mazza

As said before, contrarily to the African one, the Asiatic elephant can be, basically and within certain limits, tamed and utilized as beast of burden. This particular circumstance, united with the eco-landscape and climatic territorial transformations, not forgetting the poaching, finalized to the collection of the ivory of the tusks and of the skin, has already caused the irreversible disappearance of some races, and has led the species dramatically very close to the extinction. In fact, in the past, it was found also in Persia (the present Iran), in Java and in Mesopotamia (present Iraq), regions where it has disappeared.

The Asiatic elephant has in its skeleton 19 pairs of ribs and 33 caudal vertebrae, the African one, instead, has 21 pairs of ribs and 26 caudal vertebrae.

The females of the Asiatic elephants have a gestation period lasting about 645 days.