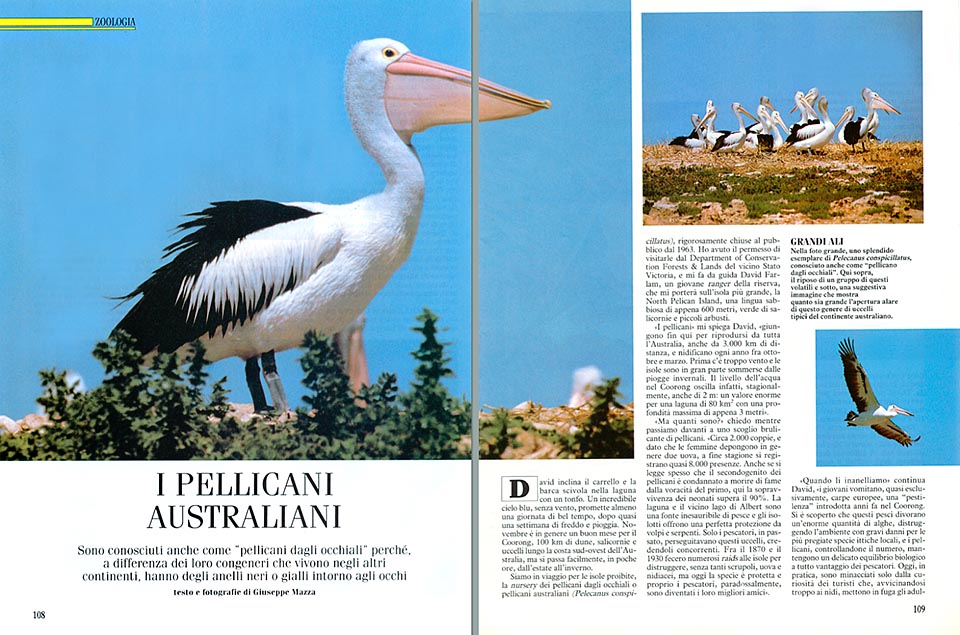

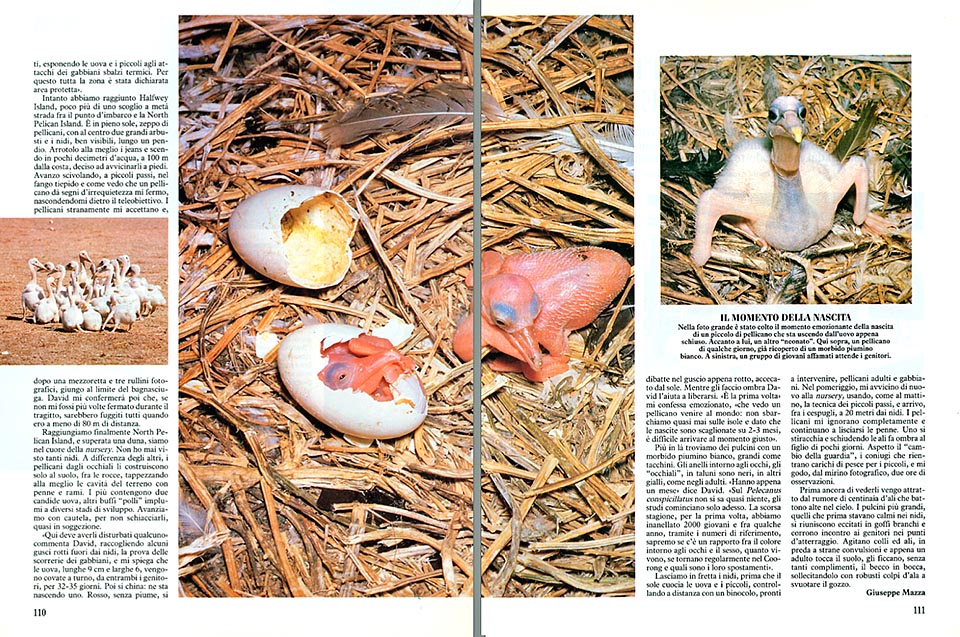

Australian pelicans. They are also known as “ spectacled pelicans ” because, unlike kindred species that live on other continents, they have black or yellow rings around their eyes. Spectacular hatching of an egg.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

David inclines the cart, and the boat glides into the lagoon with a splash. From time to time, the small metallic boat touches the bottom, and we push it out to the sea, with difficulty, sinking into the slimy mud.

An unbelievable blue sky, without wind, promises one day of nice weather at least, after almost one week of cold and rain. Usually, November is a good month for Coorong, 100 Km. of dunes, glasswort and birds along the southeast coast of Australia, but we can pass easily, in few hours, from the summer to the winter.

“It’s OK”, David shouts, and while he carries the jeep in the dry land, I set in order on board: two Hasselblads with several lenses, the 800 mm, a robust easel, a flash, the picnic bag with the films, and a large plastic cloth to protect the apparatus from the sprays of the outboard. Here, the salinity is three times superior than in the ocean, and few drops would be sufficient to compromise them for ever.

We are leaving bound to the forbidden islands, the “nurseries” of the Spectacled Pelicans, or Australian Pelicans (Pelecanus conspicillatus), rigorously closed to the public since 1963.

I have got the permission to visit them, with discretion, through the influential support of Dr. Cowling, of the Department of Conservation Forests and Lands, of the close by State of Victoria, and, as guide, I have David Farlam, a young ranger of the reserve. He is very busy with the bulldozer, in the construction of a road among the dunes, and his boss has “lent” him to me unwillingly, muttering a “till around ten o’clock, no more”. He will take me to the largest island, the North Pelican Island, a sandy stripe of only 600 metres, green of glasswort and small shrubs, and will come back in the afternoon, to take me back.

“Pelicans”, David explains, “come here to reproduce from all Australia, even from 3.000 Km. of distance, and nidify every year between October and March. Before, it’s too much windy, and the islands are mostly flooded by the tropical rains. The level of water in Coorong varies, in fact, depending on the season, even of 2 metres: a huge value for a lagoon of 80 square kilometres, with a maximum depth of only 3 metres.”

“But, how many are they?”, I ask, while we pass in front of a rock swarming of pelicans.

“About 2.000 couples, and seen that females usually lay two eggs, by the end of the season, there are about 8.000 presences.

Even if often we read that the second-born of pelicans is sentenced to death for starvation, due to the voracity of the first one, here the survival of newborns is more than 90%. The lagoon and the near Lake Albert, are an inexhaustible source of fish, and the islets give a perfect shelter against foxes and snakes.

Only fishermen, in the past, were persecuting them, considering them as their competitors. Between 1870 and 1930, they made several raids on the islands, to destroy, without many hesitations, eggs and fledge wings, but nowadays, this species is protected and just the fishermen, paradoxically, have become their best friends.”

I look at him, surprised.

“When we put them the rings,” he goes on, “the young specimen vomit, almost exclusively, European carps, a “plague”, introduced years ago in the Coorong. It has been discovered that these fishes eat an enormous quantity of algae, thus destroying the environment, with serious damages for the more valuable local species, and the pelicans, controlling their number, maintain a delicate biological balance, which is very profitable for fishermen.

Nowadays, practically, they are threatened only by the curiosity of tourists, who, approaching the nests too much, put to flight the adults, exposing the eggs and the young to the attacks of seagulls and to dangerous thermal changes. For this reason, the islands and the lagoon, 140 metres around, have been declared “Prohibited Area”, and all boats must, always, keep clear.”

“Stop, stop,” I scream, enthusiast, “These ones deserve a photo!”

It’s Halfway Island, smaller than a reef, at half way between the embarkation point and North Pelican Island. It’s in broad sunlight, packed of pelicans, with at the centre, two large shrubs and the nests, well evident, along a slope. I roll up, at my best, my jeans, and I go down in a few centimetres of water, 100 metres far from the coast, decided to approach them on foot. I proceed slipping, by short steps, in the warm mud, with the 500 mm already mounted on the easel. As soon as I see a pelican showing signs of inquietude, I stop, hiding behind the telephoto lens, and I shoot a photo with the timer, at 1/30, in order to increase the diaphragm, thus getting the full colony well focused.

I always think that the last one could be the last “clock”, but the pelicans, oddly, accept me, and after half an hour and three films, I reach the limit of the littoral zone. David, later on, will confirm me, that without any halt, the pelicans would have flown away to at, at least, 80 metres of distance.

At last, we reach North Pelican Island, and, passed a dune, we are in the heart of the “nursery”. I have never seen so many nests. Unlike the others, the Australian pelicans build them only on the soil, between the rocks, covering at the best the holes of the ground, with feathers and branches. Most of them contain two candid eggs, others, funny “fowls”, unfledged and at various stages of development. We go ahead with circumspection, in order not to crush them, almost feeling uneasy.

“Here somebody must have disturbed them,” David says, picking up some broken shells out of the nests, the evidence of raids of the seagulls, and explains me that the eggs, 9 cm. long and 6 wide, are brooded, by turns, by both parents, for 32-35 days? Then, he bows down: “There is one appearing tight now.”

Red, featherless, flounders in the shell, blinded by the sun. David helps it to get free, while I make some shade.

“It’s the first time,” he avows to me, moved, “that I see a pelican coming to life: we almost never disembark in these islands, and seen that the births are distributed on 2-3 months, it’s difficult to get here at the right moment.”

Further ahead, we find some chicks with a white, soft plumage, as big as turkeys. The rings around the eyes, the “spectacles”, are black in some of them, yellow in others, as for adults.

“They are just one month old,” David continues, “and perhaps they are males and females. We know almost nothing about the Pelecanus conspicillatus, and studies are starting only now. During last season, for instance, we have placed rings on 2.000 young specimen, and i a few years, by means of the reference numbers, we shall know if there is a connection between the colour around the eyes and the sex, how long they live, if they return regularly to Coorong, and which are their displacements.”

We leave the nests, hurried, before the sun cooks the eggs, and the young , controlling from far away with the binoculars, ready to intervene, pelicans and seagulls.

I leave David, definitely late on the programme, and after a snack, in the afternoon, I approach again the “nursery”, with the 800 mm on my shoulders. I employ, as done in the morning, the technique of the short steps, and I get, between the shrubs, at 20 metres from the nests. The pelicans ignore me completely, and go on in preening the feathers. One stretches itself, and, opening the wings, makes shade to the son, born just a few days before.

I wait for the “change of watch”, the consorts which come back, loaded of fish for the young, and I enjoy, through the view-finder, two hours of observations.

“Flap, flap, flap.” Even before seeing them, I am attracted by the noise of hundreds of wings which flutter, high in the sky. I would like to have with me the “normal”, to film the whole flock, but, in order to have less weight with me, I have left the bulk of the equipment on the beach, and with my monstrous telephoto lens, I am not even able to focus them.

As a compensation, I am witness, from far away, of an incredible sight. The bigger chicks, those which, before, were staying calm in the nests, gather, increasingly excited, in clumsy flocks, and run towards the parents, in the landing points. They shake necks and wings, overwhelmed by strange convulsions, and as soon as an adult lands, they introduce, without any ceremony, the beak into the mouth, hastening it, with strong hits of their wings, to empty the crop.

“You have been incredibly lucky.” David will tell me, coming back, punctual, at four o’clock, “Last week a famous American reporter, dressed in a mimetic overalls, has tried, in vain, to photograph the feeding of the young, and has caught only a cold.”

SCIENZA & VITA NUOVA – 1990