The devil exists and comes from Tasmania : it is the Sarcophilus arrisi, the last great carnivorous marsupial; it has very strong teeth and a very bad temper. There are also other marsupial predators, similar to cats, rats and mice.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

“An increasing moaning in the night, followed by choleric coughs or angry guttural shrieks, depending on the hunger of the animal.”

In this way, the first settlers described the unpleasant “voice” of the Tasmanian Devil (Sarcophilus harrisi).

Four robust eye teeth, well in evidence, and two dark, crazy like, eyes, which seem to start out of the head at each outburst of fury, fully confirm to me the rightness of this name.

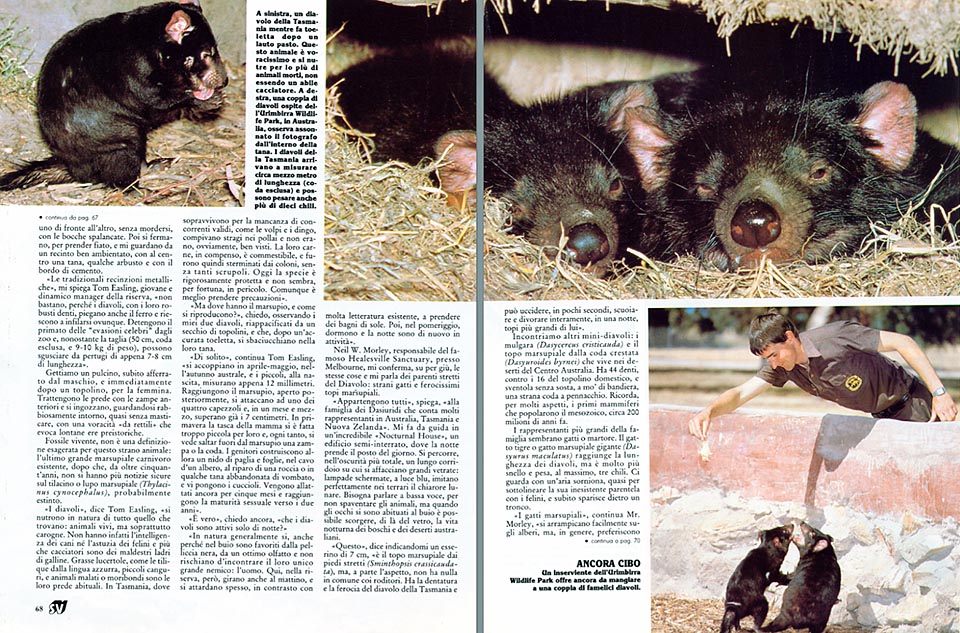

I am in the Urimbirra Wildlife Park , of Victor Harbor, Australia, a reserve which gives hospitality to two wonderful specimen, just arrived from the forests of Tasmania. They quarrel, for the best bits, screaming, face to face, without biting, with their mouths wide open. Then, they stop to take breath, and look at me from a well organized enclosure, with a den in the middle, some bushes and a cement border.

“The traditional metallic fences”, Tom Easling, young and active manager of the reserve, explains to me, “are not sufficient, because the Devils, with their strong teeth, bend also the iron and succeed in slipping into everywhere. They hold the record of the “famous escapes” from the zoo, and, in spite of the size (50 cm, tail excluded, and 9-10 Kg of weight), they can slip away through openings of only 7-8 cm.”

We throw a chick, immediately seized by the male, and, just after, a little mouse for the female.

They keep the preys with the fore claws, and swallow them, looking around with rage, almost without chewing, with a “reptilian” greediness, which recollects remote prehistoric ages.

“Living fossil”, is not an exaggerated definition for this strange animal: the last existing big carnivorous marsupial, after that, since more than 50 years, there is no more sure news about the Thylacine, or Tasmanian wolf (Thylacinus cynocephalus), most probably extinct.

“The Devils”, Tim Easling says, “feed in nature of all what they find: living animals, but, especially, carrions. In fact, they do not have the intelligence of the dogs, and the astuteness of the felines, and, more than “hunters”, they are clumsy “hen thieves”. Fat lizards, like the blotched blue-tongued skink, little kangaroos, and sick or dying animals, are their customary victims.

In Tasmania, where they survive, due to the lack of valid competitors, like foxes and dingoes, they were doing massacres in the poultry-yards, and therefore, were not beloved. Their flesh, as a compensation, was edible, and so they were exterminated by the farmers, without many qualms. Nowadays, the species is rigorously protected, and does not seem, luckily, to be in danger”.

“But, where do they have the marsupium, and, how do they reproduce?”, I ask, observing my two Devils, pacified by a bucket of small mouses, which, after an accurate toilette, keep on kissing inside the den.

“Usually,” Tom Easling goes on, “they mate in April-May, during the southern autumn, and the young, at their birth, measure only 12 mm. They reach the marsupium, open on the back side, they stick to one of the four teats, and, after one and a half month, they are already more than 7 cm long.

By the springtime, mother’s pouch has become too small for them, and, every now and then, you can see a paw or the tail, leaping out from the marsupium. The parents build then a “nest”, with straw and leaves, in the hollow of a tree, under the shelter of a rock, or in some abandoned den of wombat, and place the puppies there. They are nursed for five months more, and reach the sexual maturity when about two years old.”

“Is it true,” I ask again, “that Devils are active during only night time?”

“In nature, generally, yes, also because, in the darkness, they are favoured by the black fur, by an excellent smell, and they do not run the risk to meet their only big enemy: the man.

Here, in the reserve, however, they go around also in the morning, and often tarry, contrary to much existing literature, to tan under the sun. Later, in the afternoon, they sleep and the following night are again active.”

Neil W. Morley, responsible of the famous Healesville Sanctuary, near Melbourne, confirms to me, more or less, the same things, and tells me about the “near relatives” of the Devil: odd cats and very wild marsupial mice.

“They all belong, ” he explains to me, ” to the family of the Dasyuridae, which counts many specimen in Australia, Tasmania, and New Zealand”, and leads me in an incredible “Nocturnal House”, a semi-interred construction, where the night replaces the day. We go through, in the most total darkness, a long corridor, on which appear large windows: soft lamps, with a blue light, imitate perfectly the moonlight in the terrariums.

We have to speak low, not to scare the animals, but, when the eyes get used to the darkness, it is possible to perceive, beyond the glass, the nocturnal life of the Australian woods and deserts.

“This,” he says, showing me a 7 cm little creature, “is the Fat tailed dunnant (Sminthopsis crassicaudata), but apart the appearance, he has nothing in common with rodents. It has the teeth and the ferocity of the Tasmanian Devil, and can kill, in a few seconds, flay, and eat entirely, in one night, mouses bigger than it.”

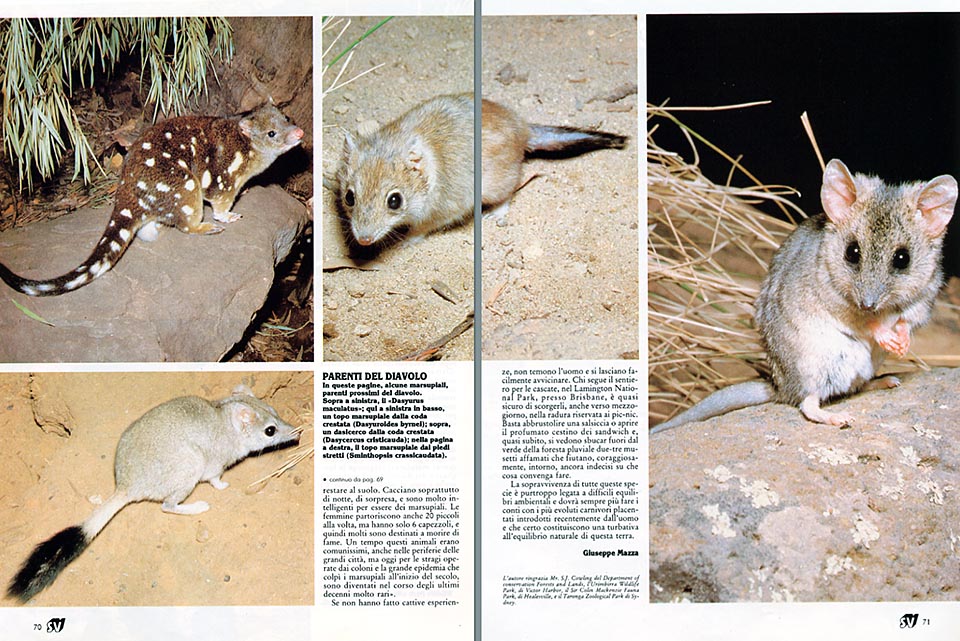

We meet other mini-devils: the Crest-tailed Mulgara (Dasycercus cristicauda), and the Kowari (Dasyuroides byrnei), which lives in deserts of Central Australia. It has 44 teeth, opposite to the 16 of the domestic little mouse, and shakes incessantly, like a flag, a strange crested tail. It recalls, for many aspects, the first mammals which populated the Mesozoic, around 200 millions of years ago.

The biggest specimen of the family, look like cats or martens. The Tiger cat, or Tiger Quoll (Dasyurus maculatus), has the same length as the Devils, but is much more slender and weighs a maximum of three kilos. It looks towards us with a wily expression, almost to underline its non-existent relationship with felines, and disappears under a trunk.

“Marsupial cats,” Neil W. Morley goes on, “climb easily the trees, but, generally, they prefer to stay on the ground. They hunt mainly during the night, by surprise, and are very intelligent, for being marsupials”.

Females deliver even 20 young at a time, but have only 6 teats, so all the others are doomed to perish of hunger. Time ago, these animals were quite common, also in the outskirts of the large cities, but nowadays, owing to the carnages done by settlers and the big epidemic which hit the marsupials by the beginning of the century, they have become very rare.

If they have not incurred in bad experiences, they do not fear men, and easily allow themselves to be approached. He who goes through the path leading to the waterfalls, in the Lamington National Park, near Brisbane, is almost sure to see them, even around noon time, in the glade kept for the picnics. It is sufficient to broil a sausage, or open the perfumed basket of the sandwiches, and, almost at once, you can see, coming out from the vegetation of the rainy forest, two-three hungry little muzzles, which, courageously, sniff around.

The survival of the species is, unluckily, connected to delicate habitat balances, and will be always much more confronted with the more developed placentate animals introduced recently by man.

SCIENZA & VITA NUOVA – 1987