Family : Notodontidae

Text © Prof. Giorgio Venturini

English translation by Mario Beltramini

The Pine processionary (Thaumetopoea pityocampa Denis & Schiffermüller, 1775) is a lepidopteran belonging to the family Notodontidae.

The name of the genus Thaumetopoea comes from the Greek thauma (θαῦμα), wonder, admiration and poieo (ποιέω), I do, hence it means “that generates wonder”, due to the extraordinary processions of the caterpillars. Also the specific name pityocampa comes from the Greek pitus (πιτυσ), pine and campe (καμπη), caterpillar and means “caterpillar of the pine”. Pityocampa was the Latin name of the pine processionary and pityocampe (πιτυοκαμπη) the Greek one.

To the genus Thaumetopoea belong other six species among which we remind the oak processionary (Thaumetopoea processionea Linnaeus, 1758) that, like the pine one, represents an important harmful agent for the forest heritage and for the health of the man.

This moth is famous for the serious damages it causes to the pines, for the strong stinging power of its hairs and especially for the behaviour of its caterpillars, that move in long rows, with every individual holding the head in contact with the rear end of the preceding (hence the common name of processionary).

The Pine processionary (Thaumetopoea pityocampa) is a Mediterranean night moth with caterpillars infesting the conifers, especially pines but also cedars. The male, pictured here, measures 3-4 cm wingspan. It is at once recognized by the pectinate antennae that allow him to quickly localize the partner in the dark © Philippe Mothiron

“Drover Dingdong’s Sheep followed the Ram which Panurge had maliciously thrown overboard and leapt nimbly into the sea, one after the other, “for you know,” says Rabelais, it is the nature of the sheep always to follow the first, wheresoever it goes. The Pine caterpillar is even more sheeplike, not from foolishness, but from necessity: where the first goes all the others go, in a regular string, with not an empty space between them.”)

In this way the great French entomologist Jean-Henri Fabre, described in the XIX century the behavior of the caterpillars of the processionary, referring to the episode of the Gargantua and Pantagruel by Rabelais where Panurge, to take revenge for the arrogance of the merchant Dindenaut, pushes into the sea the ram head of his flock, that is immediately followed by all other rams, by the merchant himself and by his servants who try to hold them. Fabre describing with great precision the behavior of the pine processionaries, narrates also his famous experiment where the caterpillars, induced to arrange themselves in a ring, go on in moving in circle for days and days regardless of frost and of the fast (even if more recent observations suggest that this astonishing result was determined by the manipulations made by Fabre: in reality the caterpillars in short time resume a normal path).

The Pine processionary is present in all temperate zones of the Mediterranean basin, where it infests several conifers, especially the pines, but also cedars.

The females, a little bigger, with thin antennae, can reach a wingspan of 5 cm © Maciej Matraj

Native to southern Europe the pine processionary, especially during the last decades, is expanding in many areas of central and northern Europe, up to the north of France, Germany, the Netherlands and England. It is possible that this expansion is one consequence of the global climatic warming, that has caused a decrease of the spring frosts.

This species, whose caterpillars nourish of the pine needles, is considered as one of the most dangerous parasites for these plants and the main factor that limits the development and the survival of the Mediterranean pine forests.

Morphology

The adults are greyish with darker transversal bands and the head adorned with thick hairs. The male, with a wingspan of 3-4 cm, is slightly smaller than the female that can reach the 5 cm.

In both sexes thorax is hairy, in the female the abdomen is bigger and covered by yellowish scales at the rear extremity. The fore wings are grey-ash with three transversal stripes, whilst the back ones are paler, with a brown dot in the anal region. The colours and the stripes are mimetic on the bark of the trees. The antennae are evidently pectinate in the male, much more slender and almost filiform in the female.

The larvae develop through 5 stages and at the last stage reach a length of about 4 cm; initially they are brown-yellowish and become darker during each moult. The tegument on the last stages is characterized by a grey-bluish to black colouration, tending ochre ventrally. The body is characterized by reddish tubercules that bear long yellow-whitish bristles, not urticant. The urticant ones, much shorter and just visible, develop mainly starting from the second moult. The head is black. The pupae, about 2 cm long, have oval shape and are reddish, wrapped by a silken cocoon of the same colour.

Biological cycle

The Thaumetopoea pityocampa, that has only one generation per year, is extremely prolific and, in some regions, with a periodicity of 6-8 years the population meets sudden strong increments. The adults emerge in summer, usually between July and August, even if at times the pupae may keep dormant in diapause for some years, up to 6, probably because of the adverse climate conditions The adults can keep hidden in the trees during the day and fly at night looking for the partner. The males usually appear the first and are better fliers than the females. The adults survive only very few days. The eggs, spherical, of about 1 mm of diametre, are white-yellowish and are laid on the trees, forming a cylindrical sleeve around the base of the needles of the pines.

Every group, formed by a very variable number of eggs, from few tens to more than 300, gets in mass a silvery colouration because is wrapped by the seta and by scales coming from the abdomen of the female.

The small whitish spherical eggs, of about 1 mm, are protected by solid silvery structures, like a sleeve, built around the base of the pine needles with the silk and scales coming from the female abdomen © Maciej Matraj

The caterpillars appear usually after about 25-40 days from the deposition of the eggs. The larvae, gregarious, nourish on the trees from autumn to spring and develop through 5 larval phases. The larvae of the Pine processionary build with the silky typical winter nests, or tents, on the crowns of the trees. The showy and unmistakable look of the nests makes easy the diagnosis of the infestation.

The nest, that usually hosts about 200 specimens, is formed by silk threads, incorporates pine needles, faces and hair of the larvae, can extend for some decimetres and is so well thermally insulated to be able to maintain a temperature over the zero even during very cold nights.

In winter the caterpillars get out from the nest for nourishing on the tree during the warmest hours of the day and usually get back by the night, always moving in single file thus forming the typical processions. If for any reason the row is interrupted the caterpillars quickly recompose it and the specimen that casually is the first becomes the new leader, that all others will orderly follow guided by an odorous trail of pheromones released by the first and reinforced by each caterpillar. When the climate gets milder the larvae get out mainly during the night.

In spring, usually between April and June, depending on the climate, the caterpillars get down from the trees and, forming the typical processions, move on the ground to interrate and pupate. The larvae coming from the same nest usually pupate all together, in thick groups. The new larvae shell in August-September, still devoid of urticant power, that appears after the second moult.

It is probable that the larvae move in single file, on a trace of pheromones, for being able to aggregate in the foraging or pupation sites and also for being able to find easily the way of the return to the nest that, as we have seen protects them so much better from the cold how much more they merge in numerous groups. On the other hand, when the caterpillars get out from the nest to eat without going far away, remaining on the adjacent branches, they move in small groups or isolated, but in any case it seems that they go back to the nest following odorous traces. It seems that in order to maintain united the row, besides the odorous trail, is also important the direct contact with the silks of the preceding caterpillar.

The pine processionary is a heliotherm species, that is, it exploits the exposure to the sun for increasing its own body temperature. The building of nests capable to hold the heat of the sun allows to the social species to control in a particular efficacious way the self temperature: seen their big size the tents of the pine processionary may host quite numerous caterpillars that, aggregating in compact masses can hold the heat in very effective way. Moreover, the nests are oriented in way to exploit in the best way the rays of the sun and their walls are so thick to prevent an excessive dispersion of the heat by convection.

We are used to believe that the heterothermic animals, that is those “with cold blood” are not able to produce heat, in way to maintain the body temperature over the ambient one. Actually, this belief is wrong, seen that every living organism with its metabolism produces a lot of heat and this turns out to be true also for the pine processionary that, even in absence of solar radiation, it can be able to maintain own body temperature at higher values than the ambient one. By measuring the temperature inside the nests it has been observed in fact that, when these are occupied by the caterpillars, they are of some grades warmer than when the caterpillars are absent.

These capacities of keeping relatively high the body temperature are particularly important for an animal like the pine processionary, whose larva is active in winter and pupates only in spring.

A sleeve open on a side: it can contain even 300 eggs and the larvae that come to life, highly social, will stay together for all their life © Maciej Matraj

Damages to the vegetation done by the pine processionary

Young trees can be completely defoliated. The defoliation weakens the plant, exposing it to the attack of other animal or fungal parasites, that can lead it to the death. In the infested areas show a decrease of more than the 20% in the annual increment of the diametre of the trunk. Apart the damages caused to the silviculture the infestation by the pine processionary can be economically important in the touristic and residential that become less attractive for the public.

The urticant action

The Thaumetopoea pityocampa, represents also a damage for the public health because the urticant power of its caterpillars that can cause important cutaneous allergic reactions, conjunctivitis and asthma. Besides the man, also the domestic animals and the cattle can be damaged by the contact with the hairs.

The urticant properties have been described well in the ancient times: already around the 300 BC, in Greece, one of the first botanists, Theophrastus of Eresos, suggests to use a plant, the Elecampane (Inula helenium) pounded with oil and wine “against the vipers, the tarantulas and the pine caterpillars” (still now this plant is utilized for the treatment of eczema and itching).

After having devoured the near leaves, the caterpillars weave together on the tree a solid silky nest exposed to the sun. It can extend for some decimetres and contain even 200 individuals that warm each other. The nest is so well insulated in order to keep inside a temperature over zero degrees also during the very cold nights © Giuseppe Mazza

Centuries later its urticant action is described by Dioscorides, a Greek physician who lived in Rome at the time of the emperor Nero, then during the first decades of the Christian era, and who calls it “pine caterpillar”. In the same years also Pliny the Elder in his “Naturalis Historia” describes the pine caterpillar and suggests also an ointment to apply on the urticated skin. The pine caterpillars were considered as a powerful poison and the Roman laws sentenced to death the poisoners who administered the “pityocampae” (larvae of the pine).

The recent expansion of the areal of the pine processionary has determined a remarkable increment of the dermatitis on the persons exposed professionally as well as among those practicing outdoor sports.

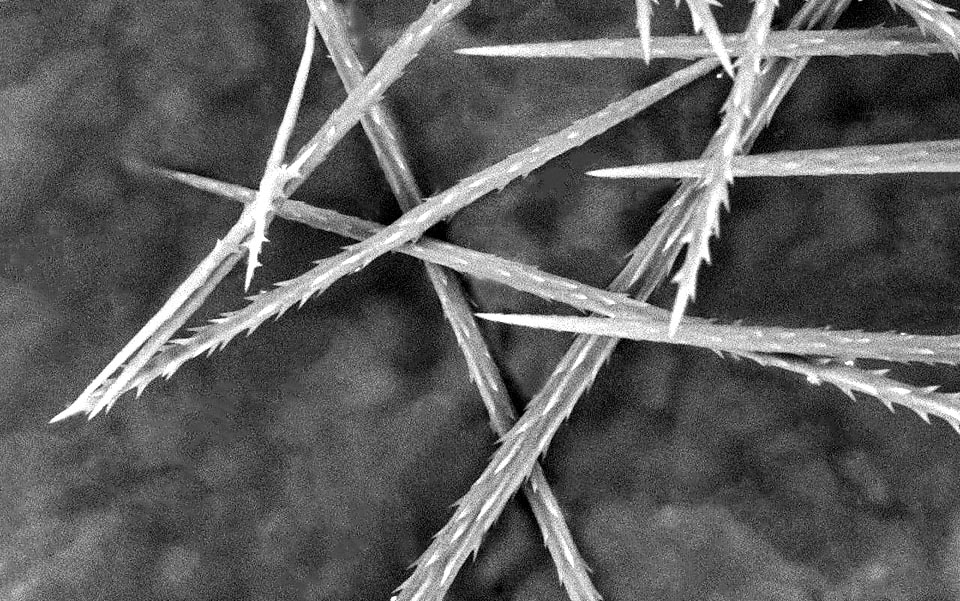

The larvae are equipped with toothed hairs about 0,2 mm long that easily penetrate through the human skin and the mucous membranes. These hairs, or setae, detach easily from the body of the animal, can be transported by the wind for considerable distances, and maintain the urticant power even for many years.

The more developped larval stages are particularly dangerous seen that each specimen may carry up to a million of hairs. At the centre of the urites (segments of the caterpillar) are present some dimples, called “mirrors”, containing up to 100.000 urticant hairs, toothed. The thinnest part is the proximal one, inserted in the mirror.

Normally the mirrors are bent, introflexed towards the inside of the body, and the hairs are just visible, protruding outside only with the extremity. When the larva is disturbed, it turns outwards the mirrors and releases the urticant setae. Since the hairs do not have an opening, their contents is released only when, penetrated into the skin, they break. The urticant effects are due to the combination between the mechanical effect of the stings and the release of allergenic proteins.

The contact with the hairs causes an allergic sensitization, with release of histamine and of other factors, that leads to a toxic-irritant dermatitis, caused by allergenic substances contained in the hair. Among these have been evidenced proteins such as the thaumetopoeins (Tha p 1 and Tha p 2), and some enzymes (serine proteases), similar to those present also in other urticant lepidopterans, and involved in the inflammatory phenomena.

The symptoms consist fundamentally in a strong itching and a reddening that usually appears in an hour and persists for more than 24 hours. In some cases appear wheals similar to those caused by insects bites. The rash appears often covered by hemorrhagic small crusts due to injuries caused by scratching because it is intensely itchy. The manifestations can be particularly serious in some patients allergic to the toxins.

The inhalation of the setae produces a strong irritation of the airways, with cough and dyspnea. When the eyes are involved arise conjunctivitis and swelling of the eyelids. The systemic symptoms may include fever, nausea and general malaise that may last even for weeks. In some very rare instances may arise an anaphylactic response even serious.

In winter caterpillars get out from nest to nourish on the tree in the warmest hours of the day and get back by evening, but when the climate is milder they usually graze by night; In spring or early summer depending on the climate, the caterpillars now mature go down from the trees. They move on the ground, in single file, to inter and pupate © Giuseppe Mazza

The contamination can happen for direct contact with the caterpillars or with the nests that, seen that by every moult the hairs are lost and then reformed, are full of urticant setae. Also the setae dispersed in the air and transported by the wind are source of health problems for the humans and for the animals. At times is used the term lepidopterism to define the systemic effects of the exposure to the larvae of pine processionary or of other lepidopterans, whilst with erucism, or dermatitis by caterpillars, is more in particular meant to describe the dermatological effects.

Predators of the pine processionaries

The caterpillars of the Thaumetopoea are preyed by some species of insectivorous birds and this represents an important mechanism of biological control that may contribute to limit the diffusion of this species. The presence of irritant hairs and the aposematic colouration discourage many birds from feeding of the pine processionaires, but some predators have developped some strategies allowing them to overcome the obstacles.

Among these birds we recall the cuckoos; that have the walls of the gizzard covered by an epithelium resistant to the urticant effects, the nightjars that seize the adults, that are not irritant; the hoopoes, that with their long bill look for the pupae hidden into the soil, or some titmice that predate the eggs or the very precocious larvae, not yet urticant, or that have developped techniques allowing to consume only the inner part of the caterpillar without exposing to the hairs.

They move, one merged to the other in the typical procession, following the odorous trail of the pheromones released by the leader and reinforced by each larva. The hairs are highly noxious. Every segment of the pine processionary caterpillar has a dimple called mirror, containing a great number (up to 100.000) of urticant setae © G. Mazza

Along the preying insects of the pine processionaries the Forest caterpillar hunter Calosoma sicophanta, that for its greediness, is considered as an important agent of control of the infestations and has been utilized in the biological struggle.

Fight against the processionary

Because of the gravity of the damages caused to the vegetation and of the dangerousness for man and animals, in many Countries exists the duty, for the owners of the woods, to report the presence of the insect and to proceed to disinfestation. The struggle against the pine processionary may be based on mechanical, chemical, biological and biotechnological means.

Among the mechanical means we remind the destruction of the nests, that however can be applied only in small areas, is problematic due to their localization in the higher parts of the trees, for the damages it may cause to the plants and because exposes the operators to the burn of the skin and of the mucous membranes due to the urticant hairs that are freed in the air. The removal of the nests furthermore creates the problem of their disposal that cannot be done simply because of the presence of the irritant hairs. A traditional system is that of destroying the nests with shotgun shots. The destruction of the nests causes the death of the larvae exposing them to the cold of the winter but on the other hand spreads in the environment the urticant hairs.

Electron microscope enlargement of the toothed setae. Rich of allergenic proteins, are released with strength, extroflecting the mirrors, when the animal is disturbed. Being very fragile, the setae break in the skin of the unfortunate botherer. They can travel in the air for several years maintaining intact all their urticant power © Andrea Battisti

Another mechanical intervention, that can be done before that the pine processionaries get out from the nests in spring consists in applying around the stem collars to preclude the larvae to reach the ground and pupate waiting for fluttering in summer. The collars, if well applied and kept clean can give appreciable results. The chemical or biotechnological fight bases on the use of chemical larvicidal preparations, of regulators chitin inhibitors of the development or of the Bacillus thuringiensis. This last method is the one most utilized nowadays and the preparation can be even diffused with the aerial means.

A promising method of struggle is that of the endotherapy that foresees to inject the pesticides directly into the vascular system of the plants, in way that they can reach the leaves and perform their toxic action on the larvae who eat them. This strategy, that allows to avoid the indiscriminate diffusion of the pesticides in the environment has been already applied successfully in the fight against the red palm weevil (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus) and is proving useful also against the pine processionary. In the biotechnological fight recourse is also done to the capture and elimination of the adult males by means of traps with pheromone-based baits: in this manner the females will lay not fecundated eggs. The biological fight is based on the use of insectivorous insects such as, for instance, Trachinids and Syrphid Dipterans Ichneumon Hymenopterans, or predatory ants.

Synonyms

Bombyx pityocampa Denis & Schiffermüller, 1774; Traumatocampa pityocampa Denis & Schiffermüller, 1775; Cnethocampa pityocampa Denis & Schiffermüller, 1928.

→ For general notions about the Lepidoptera please click here.

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within the BUTTERFLIES please click here.