Tulips, the extravagant. History and peculiarities of a flower. Nowadays we count 3.000 varieties with corollas similar to stars, peonies or roses. Latest shapes with two or more heads.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Crazy tulips with several heads; flowers resembling to stars, peonies, or roses; fringed petals dancing in the wind: it is difficult to see in the almost 3.000 horticultural varieties of the “Classified List and International Register of Tulip Names”, the now distant features of the botanical ancestors.

The founders of the family emerge, here and there, from the “cocktail” of chromosomes: the Tulipa gesneriana, the Tulipa kaufmanniana, the Tulipa greigii, the Tulipa fosteriana, theTulipa praestans, the Tulipa persica and other illustrious ancestors, often questioned by the modern systematics always more attentive, besides the flower, to the design of the pollen and to the other laws of genetics.

Once, they were talking of about one hundred species, native to Persia and Turkey, but, later on, they have discovered that many of them were simply varieties, or synonyms, or old cultivars created by man for alimentary usage; and that, on the contrary, the area of propagation of the genus was very much ample: a band wide more than 1.000 kilometres, which follows, accurately, the 40th parallel, from the Mediterranean, Italy included, to Japan, passing through Turkey, Iraq, Iran, Russia, Kazakhstan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, China, Mongolia and Korea.

It is sure, anyway, that the tulips were not in fashion in the old times. The holy texts do ignore them, and authors, such as Pedanius Dioscoridis, Theophrastus, and Pliny, for what it seems, had never seen them.

The first reproduction of these strange flowers, turban-shaped, with six tepals (the tulips have three petals and three sepals, but, as these last ones, instead of being small and green, as usual, imitate perfectly the petals, the botanists, embarrassed, have decided to call them all “tepals”), dates back to a Bible of 1200, and the Persian poet Khayyan celebrates them, in 1390, with the name of “Lale”, but we have to wait for more than one further century to find a clear scientific desceription of them, done by the Moghul Zahir Ad-Din Muhammad, called Babur, “The Tiger”, grand-nephew of Tamerlan, founder of the Mogolian Empire, and ruler of an immense territory, extending up to India.

The nobles, he relates in his memories, cultivate them in the gardens, and describes us, in detail, with botanical zeal, about thirty varieties of them.

A few years later, the fashion of these individualist flowers, ambiguous like ephebes and fresh like odalisques, conquer the Turkish court. The sultan Suleiman I, the Magnificent, poet, philosopher, and lover of the beautiful, cultivates them in abundance in the harems. And it is a regular diplomat of the Holy Roman Empire, Ogier Ghislain de Busbecq, ambassador in Constantinople of Ferdinand I, to render them known in Europe.

In 1559, he sends some bulbs to the friend Charles de l’Ecluse, better known as Carolus Clusius, French naturalist at the court of Vienna. The people there, thinking them edible, entrust them to the cooks and chemists, who macerate them, with poor success, in the sugar, or they fry them with oil and salt.

But, luckily, some of them escape from the slaughter, and the Swiss botanist-physician Konrad Von Gesner, guest of friends in Augsburg, sees them and falls in love of them at once.

He draws them, in details, with enthusiasm, and christens them Tulipa turcarum, imitating the Turkish name of “turban”. They are the ancestors of the common garden tulips, which later on, Linnaeus, will classify them in his honour as Tulipa gesneriana.

Clusius, having realized the gross error and the time lost, multiplies the survivors, and takes them with himself in Holland, where he has undertaken the position of director of the Botanical Garden of Leiden.

Showy forms come to life, and, attracted by the novelty, the rich local merchants offer him considerable amounts of money. Clusius does not want to sell them, but, during night time, somebody breaks into the garden.

In short time, the tulips become a “status symbol”, and their costs reach crazy figures: in 1636, three bulbs of the variety ‘Semper Augustus’, are paid 30.000 florins; an onion of the ‘Admiral van Enkhuizen’, 11.500 florins, and a ‘Viceroy’, bought by a crazy man, short of cash, 2.500 florins, plus 2 fat oxen, 3 pigs, 12 sheep, one cask of wine, 4 barrels of beer, 100 kilos of butter, 1.000 pounds of cheese, a bed with mattress, a wardrobe with suits, a silver vase and some other minor goods.

There is people committing suicide, for envy or due to the rage for not having the varieties in fashion, and who goes bankrupt, having speculated on the bulbs in the famous house of the Family Van der Bourse where were sold (it seems that the name of Bourse has come from here), also the royalties on the current cross-breeding, the seeds and the varieties ordered abroad.

In the apex of the “tulipomania”, a noble, relative to cardinal Mazarin, thinks to be a tulip, and orders a valet to water him, twice a day.

Luckily, in 1637, after a “technical slump” of the prices, the Dutch government ends the most crazy speculations, but the tulips have, by then, conquered Europe.

Holland, which, for historical reasons, holds, still now, the productive monopoly, devotes, every year, 7.000 hectares to the cultivation of these plants, and the modern genetics has found an important test stand in the tulips.

Submitting the bulbs to thermal shocks, and treating the plants with Colchicine, a substance which duplicates the chromosomes troubling the normal process of the cellular duplication, have come out some tulips which repeat, more than twice, their genetic patrimony.

Close to the normal forms, called “diploids”, with 24 chromosomes, we find some “triploids”, with 36 chromosomes, and even “tetraploids”, with 48 chromosomes. And if, to the human species is sufficient the splitting of one chromosome to cause big effects, such as the mongolism, you can easily imagine its consequences: plants with “obese” cells, and therefore bigger flowers and more coloured; genetic combinations before impossible, and fertile hybrids, till, in a certain way, to the “creation of new species”.

Apart collectors’ varieties, the present production concerns about 300 cultivars concentrated in 15 categories and 4 groups: the “Early Flowering Tulips”, the “Late Tulips”, the “Mid Season Tulips”, and the “Botanical Tulips”.

The first ones, simple or double, like the ‘Hytuna’, blossom, when in greenhouse, in January-February, and in open air, in March – April. They adapt very well to the strains, and, behind a well exposed window, can already be in flower by Christmas.

On the opposite side, the “Late Tulips”, on the contrary, wait for tje month of May for opening, but, generally, last longer. THey include the common single-flowered varieties, between which the famous ‘Queen of night’, almost black; the “Lily flower Tulips”, such as the ‘Maytime’, the ‘Marjolein’, the ‘West Point’, or the ‘Ballade’, similar, during the day, to stars, and, the evening, when closing, to romantic candle flames; the “Frayed Tulips”, like the ‘Fancy Frills’, or the ‘Crystal Beauty’, with its incredible ciliate tepals; the “Virdiflora”, with partly green tepals, such as the ‘Esperanto’ or the ‘Humming Bird’; the “Rembrandt”, streaked “skilfully”, by virak diseases of the bulbs; the “Peonia”, with super-double heavy flowers; and the “Dragons”, with a ruffled and twisted look, like the ‘Flaming Parrot’ and the ‘Estella Rijnveld’, obtained in laboratory, with heavy mutational bombings of X-rays.

The “Mid Season Tulips”, in bud from April to May, are much used, due to the sturdiness of the stem, by the cut flower industry. They include the famous ‘Triumph’, born from the crossing between early and late ones, with often enormous corollas like the ‘Ice Follies’, the ‘Starfire’, and the ‘Sunlife’; and the “Darwin”, like the ‘Olympic Flame’, born from the union of the first imported species with the Tulipa fosteriana.

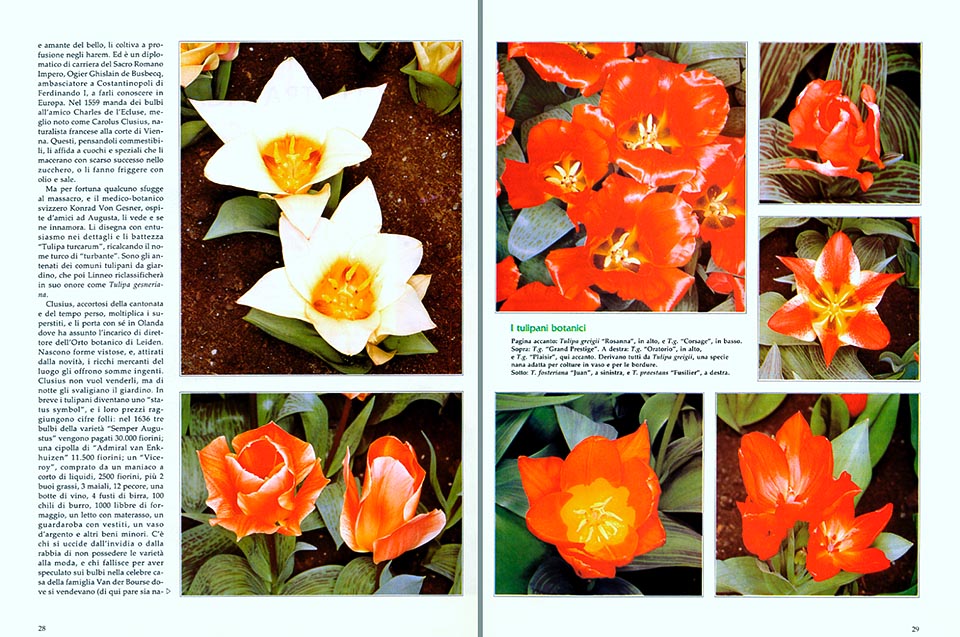

The “Botanical Tulips”, always more in fashion, boast species on the way of training, such as the Tulipa praestans, which has originated the ‘Fusilier’; the “Kaufmanniana”, with extremely early flowering; the “Fosteriana”, like the ‘Juan’, with streaked or spotted leaves; and the “Greigii”, dwarf tulips, suitable for pots and hedges, with spotted or striped leaves and often showy corollas, such as the ‘Grand Prestige’, the ‘Rosanna’, the ‘Plaisir’, or even resembling to roses, like the ‘Oratorio’, and the ‘Corsage’.

Born in 1949, from the initiative of some Dutch producers, for exhibiting to the public the bulbous in flower, the garden of Keukenhof in Lisse, is the living catalogue of all these varieties: 28 hectares, almost 15 km of alleys, 7 millions of bulbs, and 800.000 visitors in not more than seven weeks, the short period of flowering, when it is open to the public.

Here, in open air, the tulips bloom in a kaleidoscope of colours from mid April to the end of May, the narcissuses in April, and the hyacinths by the second half of the same month.

But in the 5.000 square metres of greenhouses of the park, sheltered from the changeabilities of the weather, at the same time take place the “Botanical Parades”, thematic expositions, where the last novelties are presented. Modern tulips, like the ‘Wonderland’, or the ‘Striped Sail’, two-headed, or the ‘Happy Family’, which, abandoning the individuality peculiar of the species, forms small bunches of smaller corollas, united in a joyful family on one only stem.

HOW TO CULTIVATE THE TULIPS

They can be cultivated in open air, in full land or in pot, in sunny locations, sheltered from the winds, and, indoor, behind a window, for early blossoming.

They are to be planted in October-November, so as to allow them to have the whole winter for rooting, in well drained and calcareous soils, without dung, which, especially if not well decomposed, risks to infect and rot the plants.

Chemical manures, then, and when the soil is acid, wee additions of lime on similar products, available in the “garden centres”.

At what depth are they to be placed? Usually, 10-15 cm, but even 25, if they are very big, the ground is light, or there is the risk that the small mice can eat them.

In the pots, deep at least 15 cm, they can be interred at various heights, one close to the other, in order to get spectacular degrading “bouquets”, but, generally, the distance between the bulbs must be of 10-20 cm, depending on the effect required.

Frequent spring watering, so as the substratum remains wet, and generous liquid manuring, every 2-3 weeks, will accomplish the miracle of the blossoming.

When the tepals fall, the stem is to be cut in order not to tire the bulb too much with an unnecessary production of seeds which would take 5-7 years for flowering, and it is necessary to reduce the water administrations gradually.

A couple of manuring more, so that the plant recovers from the labours of the flowering, and when the leaves become yellow, is not to be watered any more.

They will dry up, like in the native lands, for the long summer rest, but for some botanical forms, like the hybrids of Tulipa kaufmanniana, it is necessary to take off the bulbs from the soil.

They must be washed and placed to dry up in the shade, on a board. Then, after having cut the roots and the remaining leaves, at 2-3 cm from the bulb, they are to be placed, mixed with dry peat, in an old nylon stocking, hung, or in a small case, in a dark place at 16-18°C.

The small bulbs, which grow up close to the mother plant, often generate, by mutation, new cultivars.

They must be planted in autumn, as the others, at 5-15 cm of depth, depending on the size. The great ones will blossom in spring, the medium ones the next year, and the small, after 2-3 years; but it is better to renounce to the first blossoming, and cut, at their birth, the floriferous stalks, so that they have the time to grow up stronger.

Even if they are, on the whole, strong and rustic, also the tulip do not escape diseases and parasites.

Snails and slugs often eat leaves and bulbs, and it is better to eliminate them at once, with poisoned baits. A good cat will keep away the rodents, but, excepting a difficult disinfestation of the soil with specific produces, there is not much we can do against the nematodes or the viral diseases, which cause malformations and stripes, not always artistic, on leaves, stems and tepals. In these cases, the plant quickly, and, in order to avoid the propagation of the disease, it is almost always better to throw them away, change land, and restart from zero.

GARDENIA – 1991

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within LILIACEAE family please click here.