Exotic presences. The opuntias. When thorns blossom. Sculptures and delicate corollas mounted between thorns. How to cultivate them. Advice of the director of the Exotic Garden of the Principality of Monaco.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

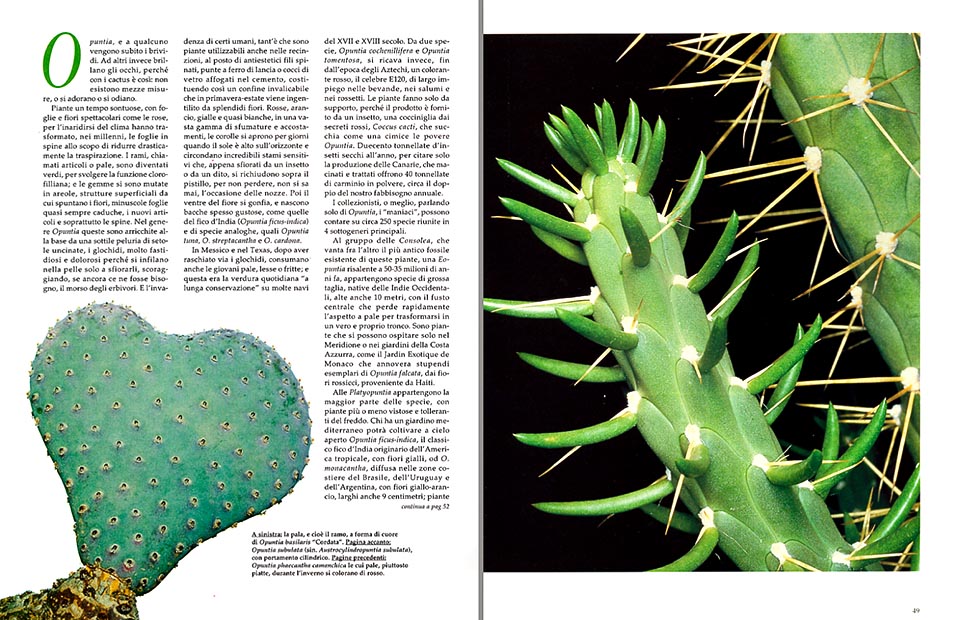

Opuntia, and somebody shudders. Others, on the contrary, have shining eyes, because with the cacti it’s like that: half-measures do not exist, either you adore, or you hate.

Sumptuous plants, time ago, with leaves and flowers, spectacular like roses, which, later, due to the drying up of the climate, have transformed, in the millennia, the leaves in thorns, in order to reduce, drastically, the transpiration.

The branches, which are here called “articuli”, or “cladodes”, have become green, to carry out the chlorophyllous function; a,d the gemmae have transformed in areolae, surface structures from which the flowers come out, tiny leaves, normally deciduous, the new articuli, and, especially, the thorns.

In the genus Opuntia, these ones are enriched at the base by a thin hair of hooked bristles, the “glochids”, very bothersome and painful, because they slip into the skin only by skimming them, discouraging, should it be needed, the bite of the herbivores.

Plants which can be used, why not, for the enclosures, in lieu of unaesthetic barbed wires, points like steel heads, or fragments of glass stuck into the cement, refined, in spring-summer, by splendid flowers.

Red, orange and yellow up to almost the white, in a wide range of tones and matchings, they open for days when the sun is high on the horizon, and have incredible sensitive stamens, which, as soon as skimmed by an insect or a finger, close over the pistil, just not to lose, you never know, the opportunity of the wedding.

Then the abdomen of the flower swells, and some berries, often tasty, come out, like those of the Prickly pear (Opuntia ficus-indica) and of analogous species, like the Opuntia tuna, the Opuntia streptacantha or the Opuntia cardona.

In Mexico and in Texas, after having scraped the glochids, they eat also the young cladodes, boiled or fried; and this was the “long conservation” daily vegetable on many vessels of the 17th and 18th centuries.

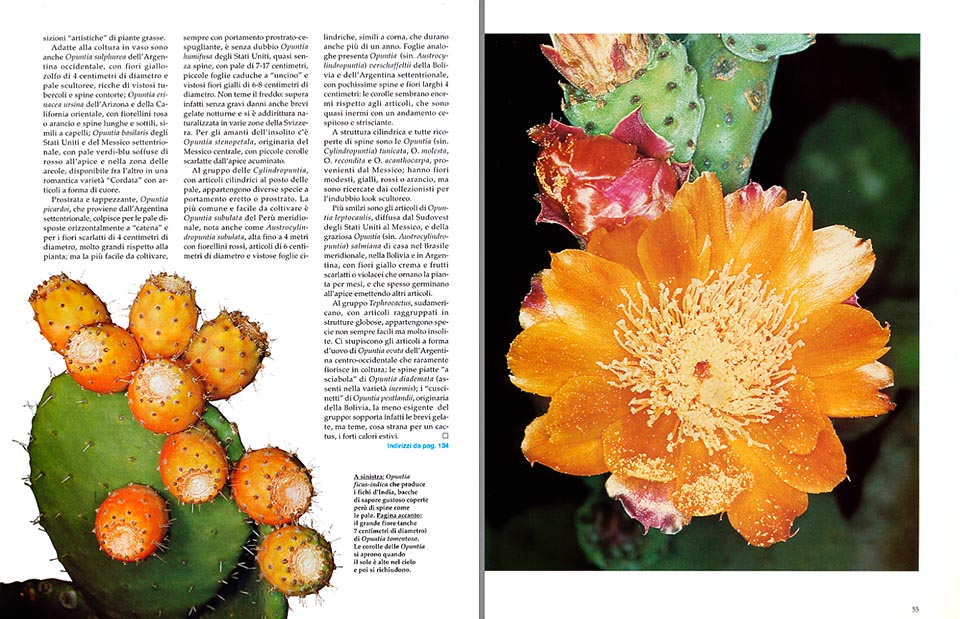

From two species, the Opuntia cochenillifera, and the Opuntia tomentosa, is extracted, since the Aztec time, a red dye, the well known E120, which is widely employed in drinks, cold cuts and lipsticks.

The plant acts only as a support, as the product, is, alas, furnished by an insect, by sure not attractive, a cochineal, with red secretions, the Coccus cacti, which sucks, like a bug, the poor Opuntia. 200 tons of dry insects per year, to cite the production of the Canary Islands only, which, ground and treated, offer 40 tons of red carmine in powder, roughly the double of our annual needs.

THE SYSTEMATICS

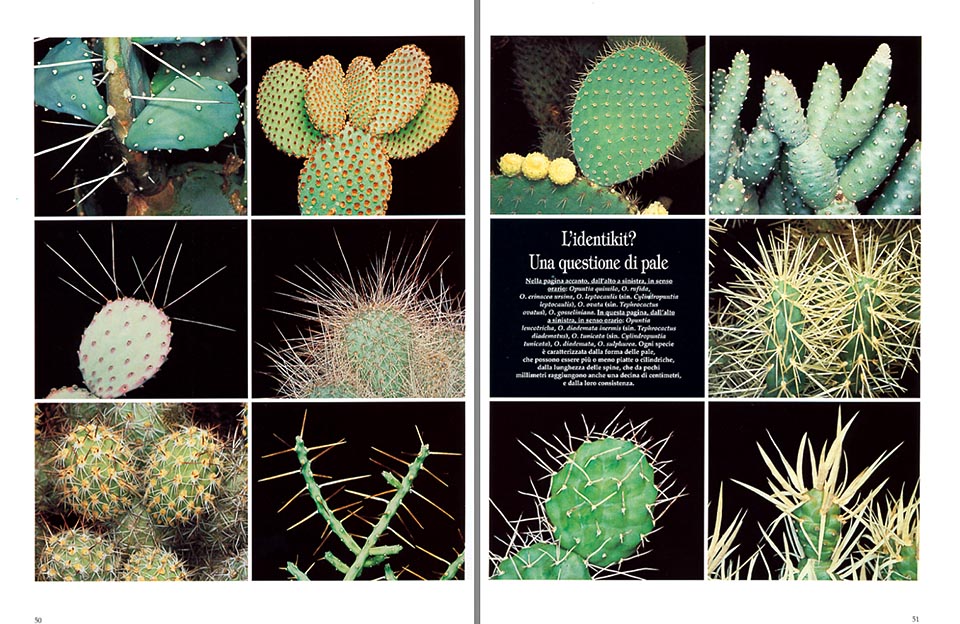

The collectors, or, better, talking of Opuntia, the “madmen”, can rely on about 250 species gathered in four major sub genera.

To the group of the Consolea, which praises, among other things, the most ancient existing fossil of these plants, an Eopuntia of 50-35 millions of years ago, belong large size plants, native of West Indies, even 10 metres tall, with the central stalk which, quickly, loses the cladodes look, to transform in a real and proper trunk. Plants which can be kept only in the South, or in the warm gardens of the Côte d’Azur, like the Jardin Exotique of Monaco, which has splendid specimen of the Opuntia falcata of Haiti, with reddish flowers.

To the Platyopuntia, the classical group of the Prickle pears, belong the most of the species, with specimen, more or less showy, which tolerate the cold.

He who owns a Mediterranean garden, will be easily able to cultivate, in open air, the Opuntia ficus-indica of tropical America, with yellow flowers, or the Opuntia monacantha, spread in the coastal areas of Brazil, in Uruguay and Argentina, with yellow orange flowers, wide even 9 cm, plants of 4 and even 6 metres of height, which bear also short-lasting frosts.

And in the locations where the lowest temperatures never go under the 4°-5 °C for long time, it will be possible to keep also several Mexican species, such as the already quoted Opuntia tomentosa, with velvety cladodes, red-orange 7 cm flowers, few thorns and real trunks, tall even 6 metres; the Opuntia cohenillifera, just a little smaller, with unusual vermilion, prolonged corollas, from where get out the stamens in bunches; the Opuntia leucotricha, of analogous size, with yellow flowers, and aromatic, white-yellowish, red or violet fruits, sold in the original countries as “duraznillo”; and the Opuntia pilifera aurantisaeta, tall even 5 metres, with red-carmine flowers.

The Opuntia quimilo of the north of Argentina, which feels the cold much more, requires lowest temperatures over 6°-7 °C, and the protection of a cold greenhouse to reach its 3-4 metres of height, with cladodes long even half a metre, brick-red flowers and showy thorns.

Accessible to all, because suitable also for the cultivation in pot, are the Opuntia grandis of the north of Mexico, not taller more than 60 cm, with yellow, 2 cm of diameter flowers; the Opuntia phaecantha camanchica, of USA and Mexico, one metre tall, with 5 cm yellow or salmon-pink flowers, and 10-15 cm cladodes, which colour of red in the cold season; the Opuntia catingicola of Brazil, of analogous size, with red small flowers sustained by queer tuberculated “cones”; the Opuntia gosseliniana, spread from Mexico to the Lower California, attractive, more than for the yellow small flowers, for the reddish cladodes in correspondence of the areolae and the presence of long, hairlike, thorns, at the apex; or the Opuntia rufida, of Texas and North Mexico, with orange flowers and wide areolae, rich of red-brown glochids.

This nice species, without horns, is often mistaken with the Opuntia microdasys albispina, of North Mexico, slightly smaller with white glochids, and pale yellow flowers, frequent in the ephemeral “artistic” compositions of succulent plants.

Suitable for the cultivation in pots, are also the Opuntia sulphurea of western Argentina, with sulphur-yellow flowers, with a diameter of 4 cm, and sculptural cladodes, rich of showy tubercles and twisted thorns; the Opuntia erinacea ursina of Arizona and eastern California, with red or orange small flowers and long and thin hairlike thorns; and the Opuntia basilaris of USA and north Mexico, with green-blue cladodes suffused of red on the apex and in the place of the areolae, available, among other things, in a romantic “corded” variety, with articuli shaped like little hearts.

Prostrate or carpet-like, the Opuntia picardoi of the north of Argentina, strikes for the cladodes ranged horizontally, like a “chain”, and the scarlet 4 cm flowers, very large in comparison with the plant; and the easier, with prostrate and bushy appearance, is, by sure, the Opuntia humifusa of USA, almost without thorns, with 7-17 cm cladodes, qmall, hook-like, deciduous small leaves, and showy yellow flowers with a diameter of 6-8 cm. It does not fear the cold, overcoming without serious damages even short nightly frosts, and has even naturalized in several areas of Switzerland. And for the lovers of the out of the ordinary, there is the Opuntia stenopetala, of central Mexico, with small scarlet corollas, with a sharp apex.

To the group of the Cylindropuntia, wiht cylindrical articuli in lieu of the cladodes, belong various species, either erect, or prostrate.

The most common and easiest to cultivate, is the Opuntia subulata of southern Peru, known also as Austrocylindropuntia, tall even 4 m, with red small flowers, 6 cm of diameter articuli, and showy cylindrical leaves, similar to horns, which last even more than one year.

Analogous horns, as also the Opuntia (= Austrocylindropuntia) verschaffeltii, of Bolivia and north Argentina, with very few thorns and 4 cm flowers, enormous, if compared to the articuli, almost defenceless, tufty and creeping.

Cylindrical structures, all thorns, coming from Mexico, are the Opuntia (= Cylindropuntia) tunicata, Opuntia molesta, Opuntia recondita, and Opuntia acanthocarpa; real “pests” in the countries of origin, with modest yellow-red or orange flowers, but “joys of the collectors”, for their undoubted sculptural look.

More slender, for anorexics, are the articuli of the Opuntia leptocaulis, spread from the south-west of USA to Mexico, and of the charming Opuntia (= Austrocylindropuntia) salmiana of Bolivia, Argentina and southern Brazil, with yellow-cream flowers and scarlet or purple fruits, which decorate the plant for months, often germinating at the apex, without any problem.

To the group Tephrocactus, entirely South American, with articuli grouped in globous structures, belong species not always easy, but unusual.

We are, so, amazed by the egg-shaped articuli of the Opuntia ovata, of central-western Argentina, which rarely blossoms when cultivated; by the Opuntia diademata, with flat thorns, like “sabers”, or without thorns in the variety inermis; and by the “small cushions” of the Opuntia pentlandii, of the tablelands of Bolivia, which is the easiest of the group. It bears, in fact, the short frosts, but fears, strange for a cactus, the strong summer heats.

CULTIVATION

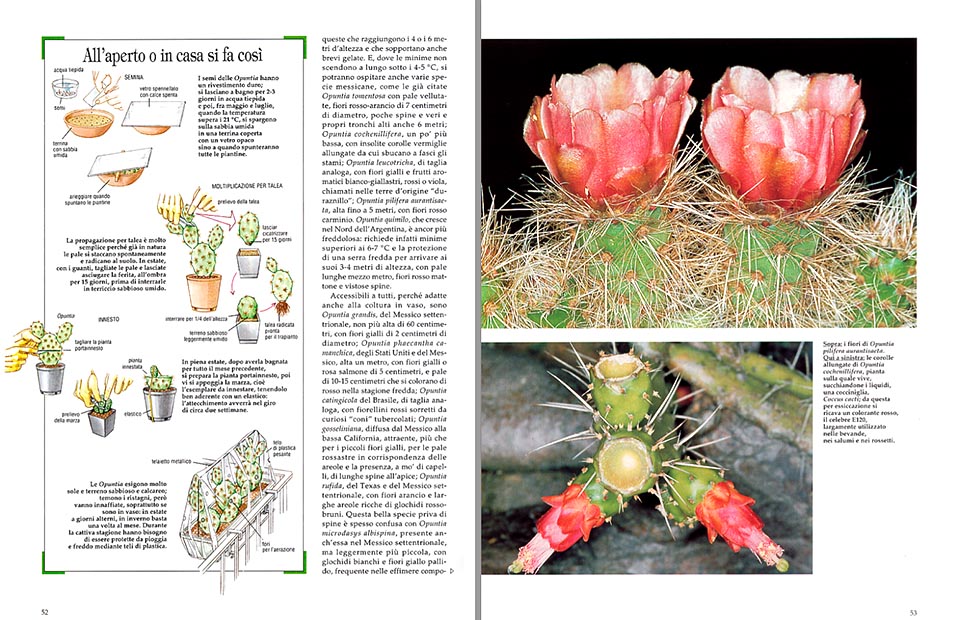

In the whole, particularly in the Mediterranean climates, the Opuntia are easy plants, which are doing well, without too many cares, in the terraces and in the gardens.

They need a lot of sun, a light soil, sandy and calcareous, poor of nitrogen, seen that they do not have leaves, but rich in phosphorus and potassium, and, contrarily of what is currently thought, of an adequate water input.

If all Opuntia, in fact, do not stand the stagnations, and need a perfect drainage, it is also true that they must not be watered with the dropper. In winter, when they rest, an administration per month is sufficient, but in summer, especially when in small pots, in a sunny terrace, they must be watered at least every other day.

In the wild, the roots go down deeply, and in the strategical positions, close to the rocks, they collect the morning dew; but in a small pot of a few centimetres, dry and compact, they die quickly of asphyxia.

The varieties which feel more the cold, especially where it rains in winter, need a roof or a provisional greenhouse done with some plastic sheets, holed for the ventilation. And, if the pots are moved to a bright veranda, not heated, they will have, later, to be exposed gradually to the sun, in order to avoid unaesthetic scalds.

GRAFTS

The most delicate species, like the Opuntia ovata, and, generally, those belonging to the group of the Tephrocactus, are to be grafted on vigorous plants, such as the Opuntia tunicata, or the Opuntia tomentosa.

In full summer, after having watered it and cuddled during the month preceding the intervention, the graft carrier is to be cut low, and we shall apply there, with an elastic bandage, paying attention not to form any air bubble, the dissected base of the articulus of the guest species. Usually, it catches on, and after 15 days, the bonds can be removed.

REPRODUCTION

The seeds of the Opuntia have a hard coating, and it is good to keep them soaking in lukewarm water for 2-3 days. Than, they are to be scattered on the wet sand, between May and July, at temperatures not lower than 21 °C, in a tureen covered by a glass rendered opaque with some lime, which can even be left in the sun. And when the small plants come out, the place must be, progressively, aired.

But, unless we don’t look for hybrids, the propagation by cutting is the most advantageous.

In the wild, the articuli detach spontaneously, rooting in the ground; and in cultivation it is sufficient, to take them off using a good pair of gloves, and a blade, to leave to wound healing, in the shade, for a fortnight, before interring them, for 1/4, in summer, in a sandy, not too humid soil.

GARDENIA – 1985