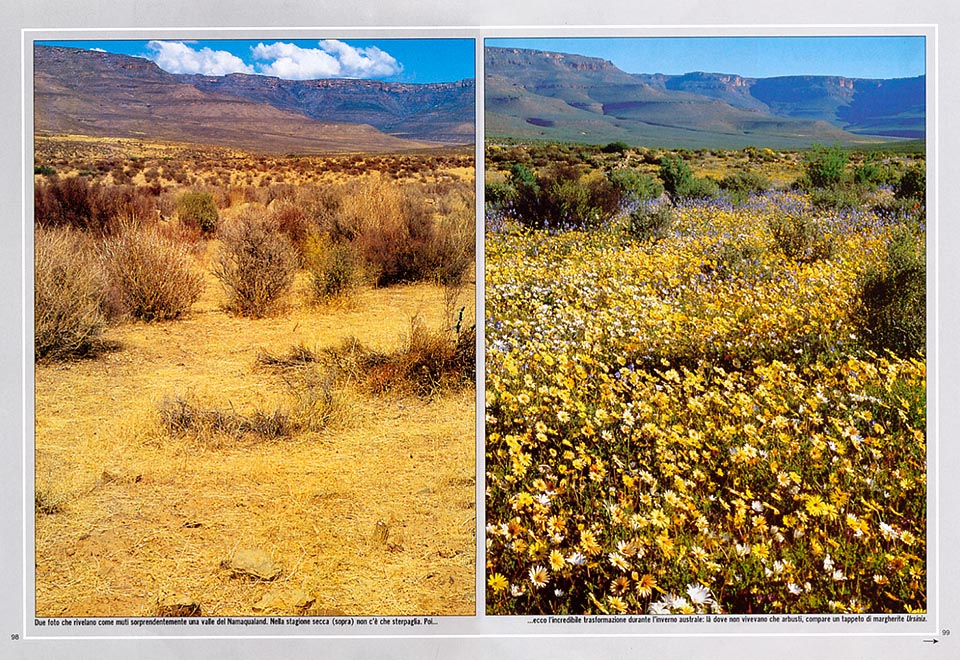

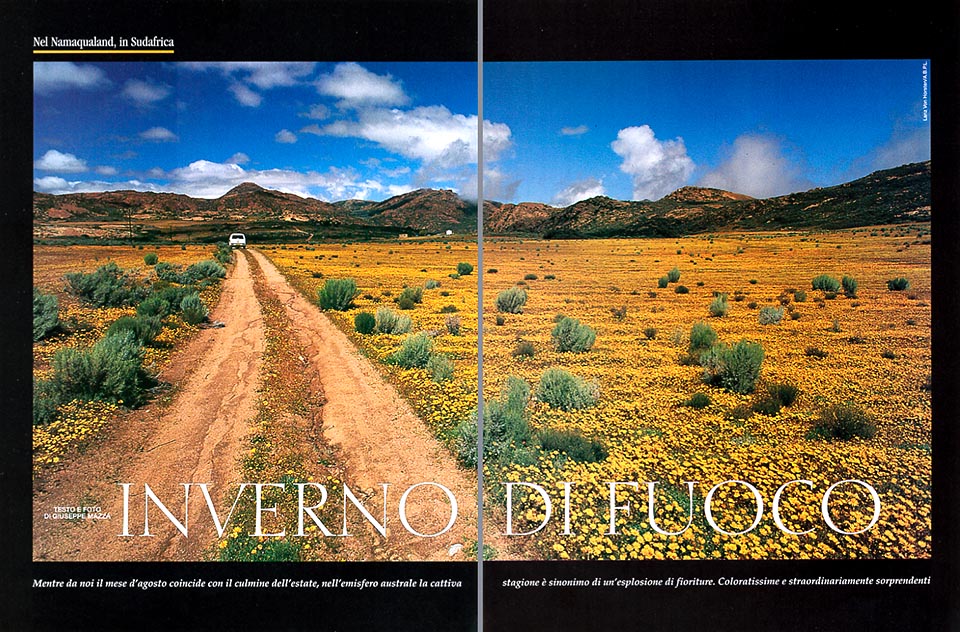

Miracle in the desert. For a month a year life blossoms in Namaqualand. In this South African region there is one of the biggest concentrations of flowers in the world. Strange and showy corollas to seduce marriage makers. Hostile climate and fight for survival force the plants to be very seductive. Spectacular photos of the dead season and of the winter when the desert blossoms. Just few days of rain and the desert changes in an ocean of colourful flowers. The seeds can wait for years. While August is for us the height of the summer, in the austral hemisphere the bad season is an explosion of flowers.

Text © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

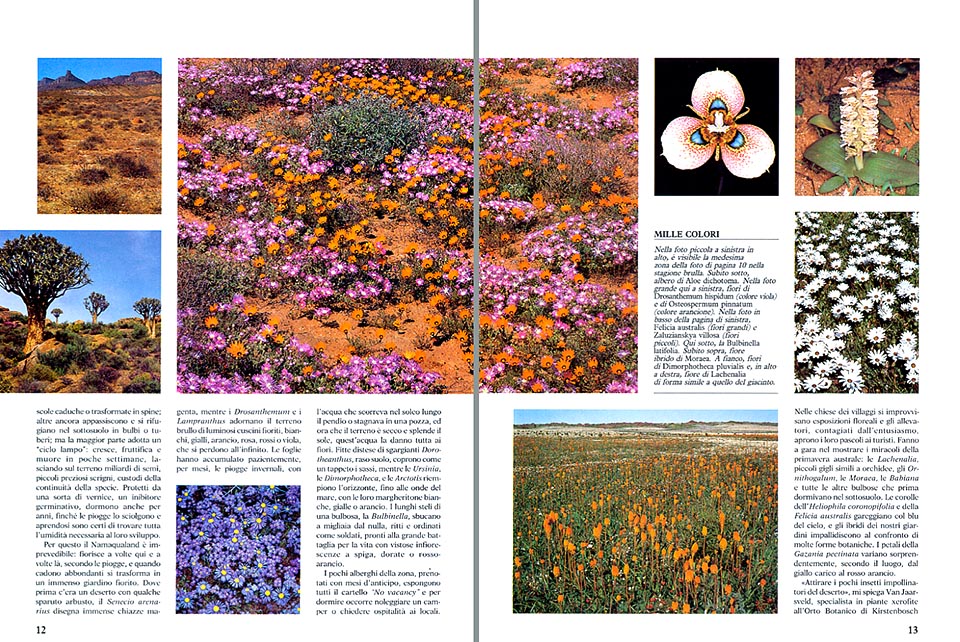

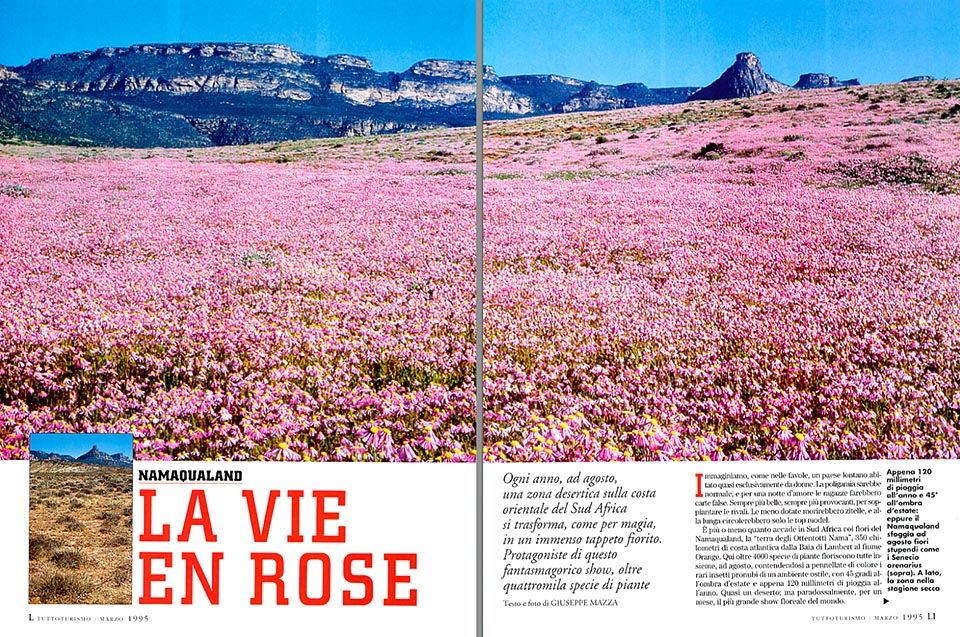

120 mm of rain per year, 45 °C in the shade, in summer, and a stony soil, by sure not fertile. It should be a desert or a brushwood, and, on the contrary, in August, it gives hospitality to the largest floral show in the world: 4.000 species, after some botanists, 7.000, maybe more, after others. And every year, they discover new ones.

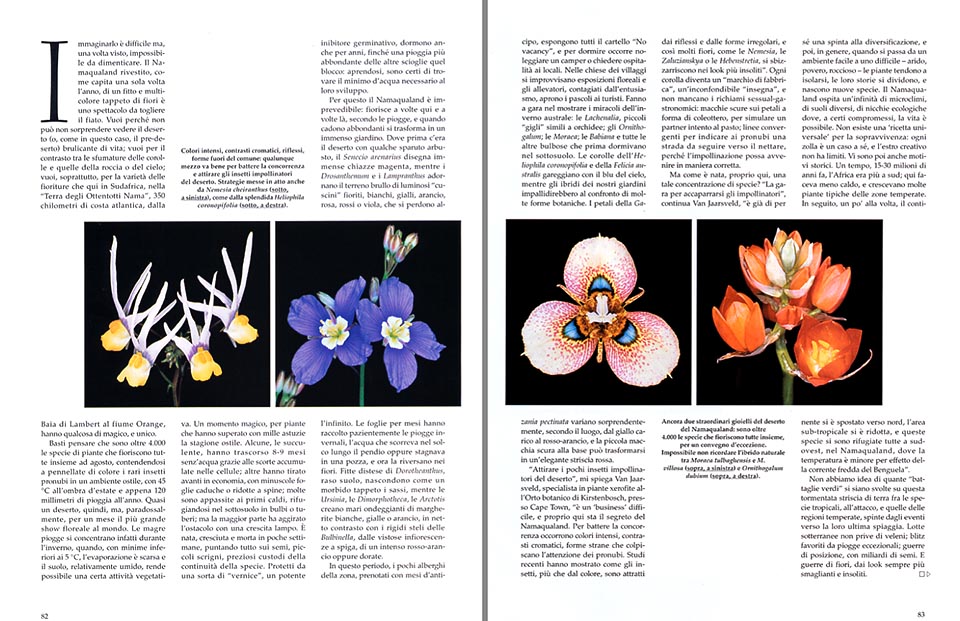

In a fast contest with the time, billions of flowers bloom, as by miracle, all together, at the end of the austral winter, and, quite illogically, in spite of the climate, they are bigger and more beautiful than elsewhere.

We are in South Africa, in Namaqualand, the “Land of the Hottentots Nama”, 350 km of Atlantic coast, from Lambert Bay to the Orange River.

The few hotels of the region, carry, since time, the notice “No vacancy”. “There is no room till mid September”, they repeat to us, and, for sleeping, we have to rent a motor-home, to seek hospitality to the local people, or to join the organized tours which book the rooms one year in advance. Many-coloured tourists, floriculturists and botanists, come from all the world to see this waving sea of corollas, of colours, variegations and endemic “designs”, often without any comparison in the traditional floras.

But, what is the secret of Namaqualand? And, above all, how such concentration of species was born here?

Ernest Van Jaarsveld, expert in succulent plants of the famous botanical orchard of Kirstenbosch, in Cape Town, advances some hypotheses.

For living in the deserts, he explains to me, usually, the plants utilize two strategies: either they store the water in the large vacuoles of the cells (succulent plants), or they reduce the loss of liquids with deciduous leaves, small, or transformed in thorns.

Here, on the contrary, almost all rely on the seeds. They have got used to grow up quickly, in winter, with very fast vegetative cycles, of a few weeks only, and avoid the drought passing away before the summer.

Should the 120 mm of rain fall when it is hot (in Italy, the annual quantity of rain fluctuates from 500 to 3.000 mm, depending on the zone, with 900 mm in Rome), Namaqualand would be a desert, but, luckily, the rain concentrates between April and August, when the lowest temperatures vary between 0 and 5 °C, the evaporation is weak, and the soil is wet enough to allow the growth.

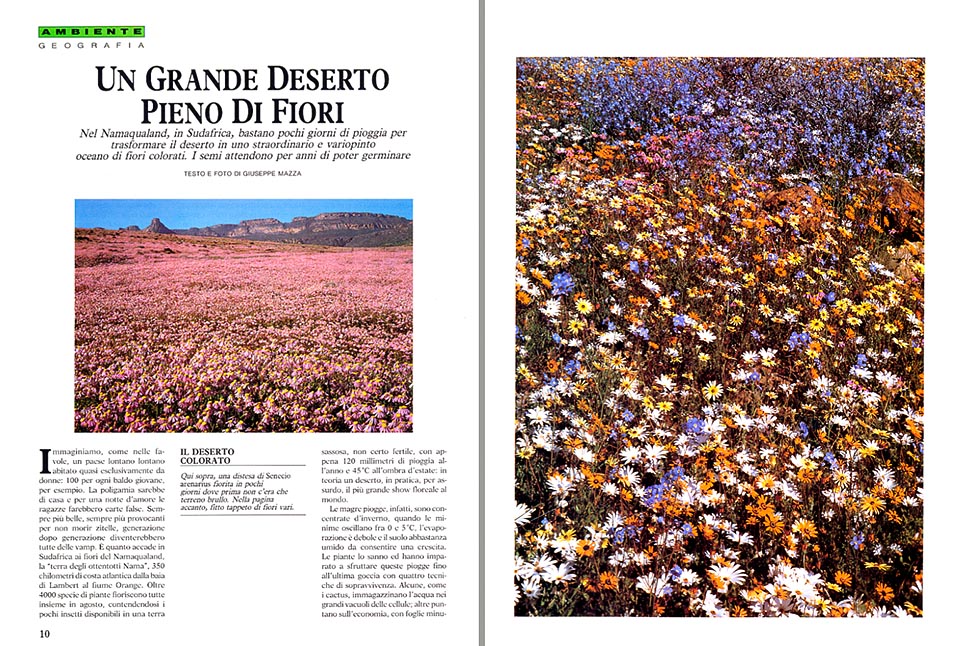

Upon the first rain, the bulbous plants wake up, come out suddenly with incredible flowers, and the annual ones grow up at sight, in order to catch them.

They must attract the few available insects, and produce billions of seeds before the arrival of summer. Small and precious coffers, keepers of the continuity of the species, these will remain in the soil even for years, without germinating, held back by particular chemical inhibitors, to explode again, later on, all together, as soon as the habitat conditions will allow it.

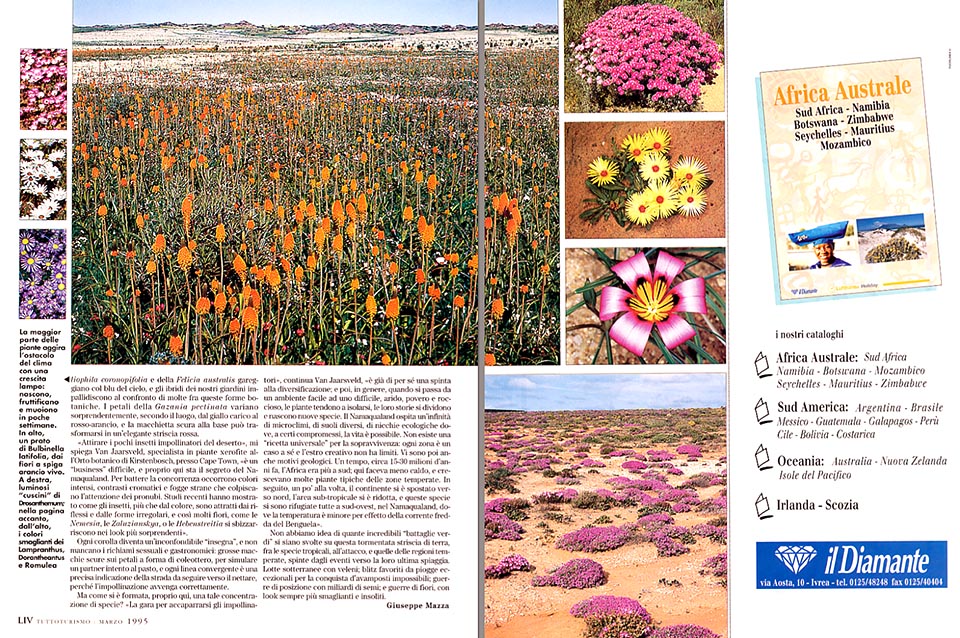

For this reason, Namaqualand is unforeseeable: it blossoms, sometimes here, sometimes down there, depending on the rains, and when these ones fall plentifully, it transforms in an immense garden full of flowers.

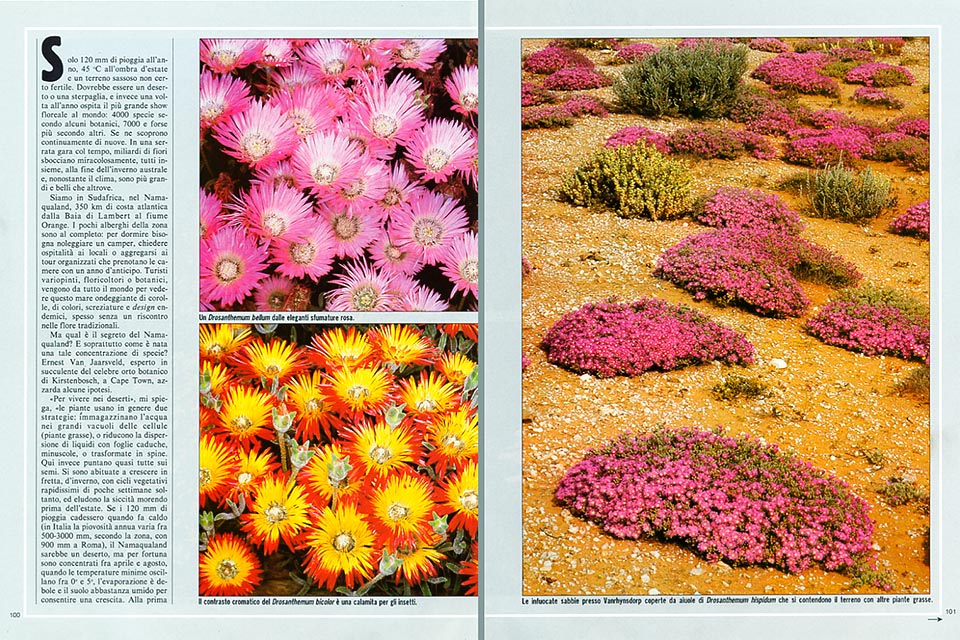

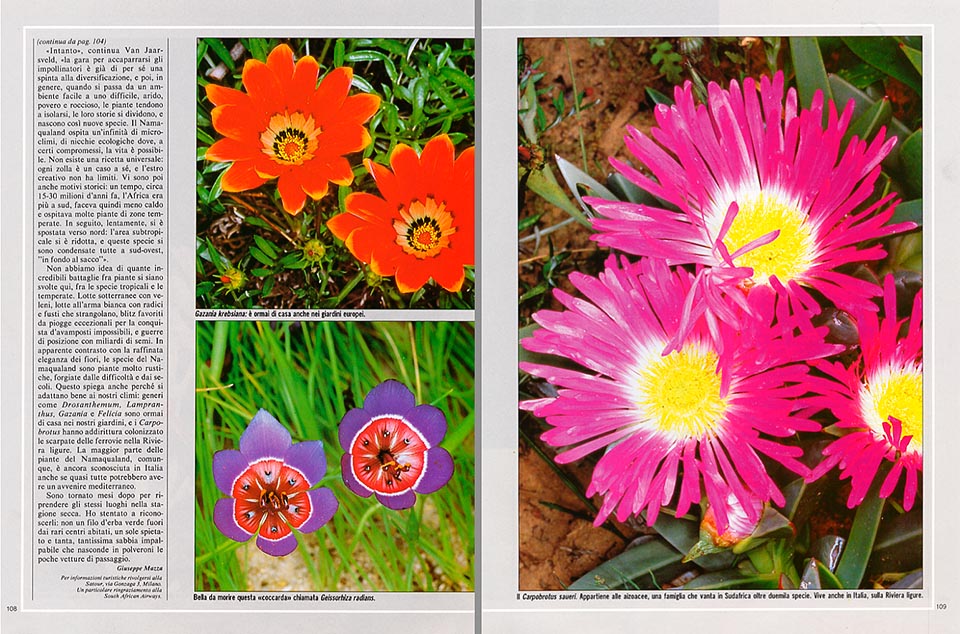

Where, before, there was a desert with just some meager shrubs, the Senecio arenarius, and the Oxalis purpurea draw huge red stains, while the bare land embellishes with the bright flowers of the Drosanthemum and the Lampranthus.

Thousands of flowered “cushions”, white, yellow, orange, pink, red and violet, vanish into the infinity. The leaves have patiently accumulated, for months, the the winter rains, the water flowing in the groove along the slope, or stagnating in a puddle, and now that the soil is dry and the sun is shining, they give it all to the flowers. Expanses of Dorotheanthus, of white, yellow and orange huge daisies (Ursinia, Dimorphoteca, Arctotis, Osteospermum, and Gorteria), fill up the eyes till the horizon, while the long stems of the Bulbinellas come out by thousands from the nothing.

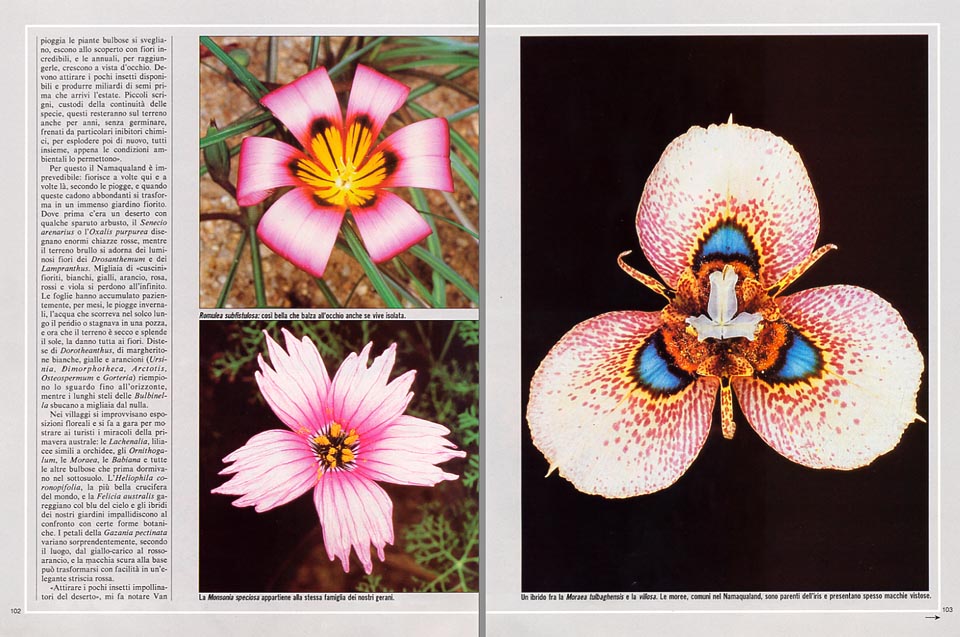

In the churches of the villages, the extemporize floral shows, and the breeders, overwhelmed by the enthusiasm, open their pastures to the tourists. They compete in showing us the miracles of the austral spring: the Lachenalia, liliaceae similar to orchids, the Ornithogalum, the Moraea, the Babiana, and all the other bulbous plants, which, before, were sleeping under the ground.

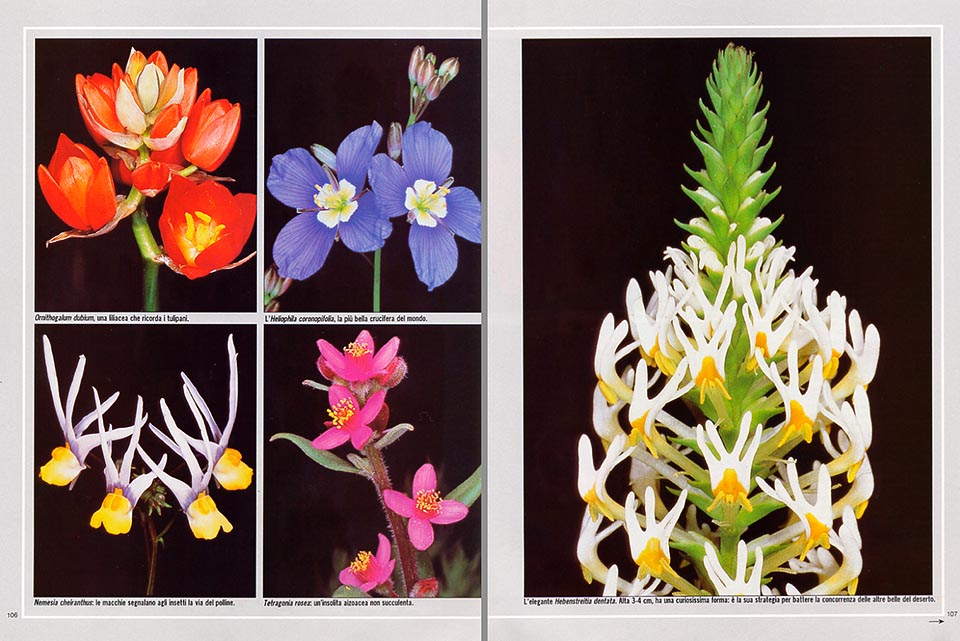

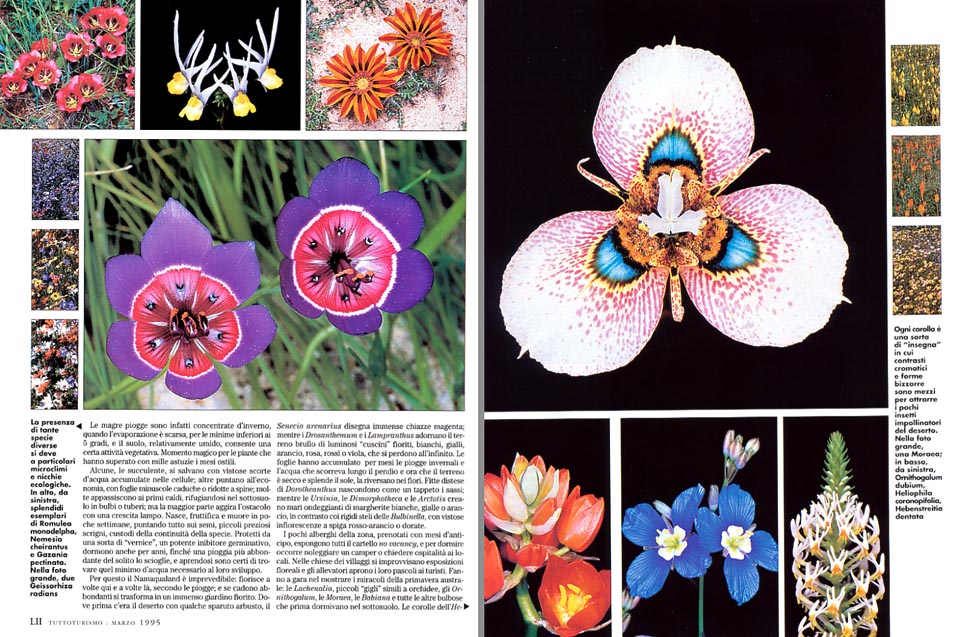

The Heliophila coronopifolia, the nicest crucifer in the world, and the Felicia australis, compete with the blue of the sky, and the hybrids of our gardens fade in comparison with certain botanical forms.

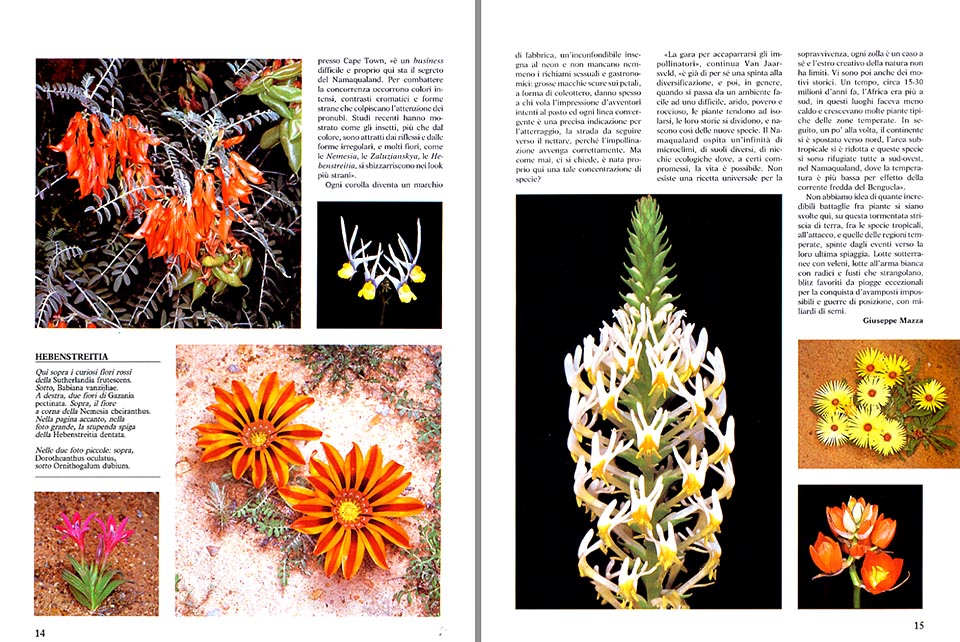

The petals of the Gazania pectinata vary surprisingly, depending on the location, from the deep yellow to the red-orange, and the small dark dot on the base, can transform into an elegant red stripe.

To attract the few pollinating insects of the desert, Van Jaarsveld points out to me, is a difficult “business”, and it’s well here where stands the secret of Namaqualand.

For the defeating the concurrence, they need strong colours, chromatic ones, and unusual forms which have to catch the attention of the pollinators.

Recent studies have demonstrated that the insects, rather than by the colour, are attracted more by the reflections and by the irregular forms; and so the Nemesia, the Zaluzianskya, the Hebenstreitia, and many flowers engage in very unusual matchings.

And the sexual and gastronomical reminders are not missing: big dark dots on the petals often imitate coleopters intent on the meal, and like our road signs, or the magazine covers, catch the attention of the passers-by.

Every convergent line is a precise indication for the sight landing of the insects: the way to follow, towards the nectar, in order that the pollination takes place correctly.

Nothing is left to the chance, and the selection is extremely hard. It is like if in an hypothetical and terrible sexist country, where almost exclusively women come to life, marriages could take place, by law, only in February (our climatic equivalent of the austral August), and the old maids should be then sentenced to death. Without being obliged to wait for Carnival, all the “tricks” would be valid, and, after a few years, along the roads there would be only wonderful girls.

A delight for the eyes, as it happens in Namaqualand. The flowers, after all, are “seduction machines”: they promise nectar in exchange of the carriage of pollen, and if the “postmen” are lacking, if the competition is great, the race to the pollination becomes the race for the life.

With such premises, the first reaction of every plant is to place out the petals, the “signs”of its restaurant, before the others, but seeing that the vegetative period is very short, they end up in blossoming all together.

To survive, then, they must diversify: the “individualists”, make themselves conspicuous with bright “neon signs”, unmistakable trade-marks of their good cuisine, and the less endowed flowers, the “socialists”, group and aim, as always, at the quantity. They unite the corollas in spikes, or daisy-like structures, imitating the big individualist flowers, and, not yet happy, convinced, as they are, that union makes strength, throng the inflorescences one upon the other, in boundless fields in flower.

But, how was it born, just here, such a concentration of species?

The fact remains that, Van Jaarsveld continues, the competition for gaining the pollinators is already, by itself, an incentive to the diversification, and then, as a rule, when they pass from an easy habitat to a difficult one, arid, poor and rocky, the plants tend to isolate, their histories part, and, in this way, new species come to life.

Namaqualand has an infinity of micro climates, of ecological niches, where, following certain compromises, life is possible. A universal recipe does not exist: each sod is a case apart, and the creative impulse has no limits.

Then, there are also historical reasons: Africa, about 15-30 millions of years ago, was located more to the south, therefore it was less hot, and was giving hospitality to many plants of the temperate areas. Later on, slowly, Africa moved northwards: the sub-tropical area has reduced, and these species have concentrated all in the south west, “in the bottom of the sack”, where the temperature is lower, also due to the cold stream of Benguela.

We have no idea of how many battles between plants have taken place here, on this tormented strip of land, between tropical and temperate species, pushed by the events towards their last chance.

Underground struggles with poisons, fightings with the cold steel, with roots and stems which strangle, blitzes supported by exceptional rains for the conquest of impossible outposts, and wars of position with billions of seeds.

Using the words of the French song singer and writer, François Cabrel in “Je l’aime à mourir”, these flowers must really have done all the wars of the life, for being now so nice and strong.

In apparent contrast with the refined elegance of the flowers, the species of Namaqualand are very rustic plants, shaped by the difficulties and the centuries. This explains also why they adapt so well to our climates. Genera such as Drosanthemum, Lampranthus, Gazania and Felicia, are by now familiar in the gardens, and the Carpobrotus have even colonized the railway escarpments, but most of these plants are still unknown in Italy.

Almost all of them, they confirm me in Kirstenbosch, might have easily a Mediterranean future.

I have come back in March, Hasselblad slung over my back, to film the same plants in the dry season. I had problems in recognizing them: not even a single blade of grass out of the few inhabited centres, a pitiless sun which breaks stones and much, very much, impalpable sand, which enters everywhere, and transforms in long clouds of dust, visible kilometres far away, the few passing-by cars.

NATURA OGGI + SCIENZA & VITA NUOVA + TUTTOTURISMO + GARDENIA – 1988