Commonly called grass trees or black boy, this Australian plant can live over 900 years and doesn’t fear fire; indeed it gets advantage from fires. Used to make gum powder and paint. By the analysis of remains of leaves it is possible to determine the evolution of pollution and radioactivity in the air.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

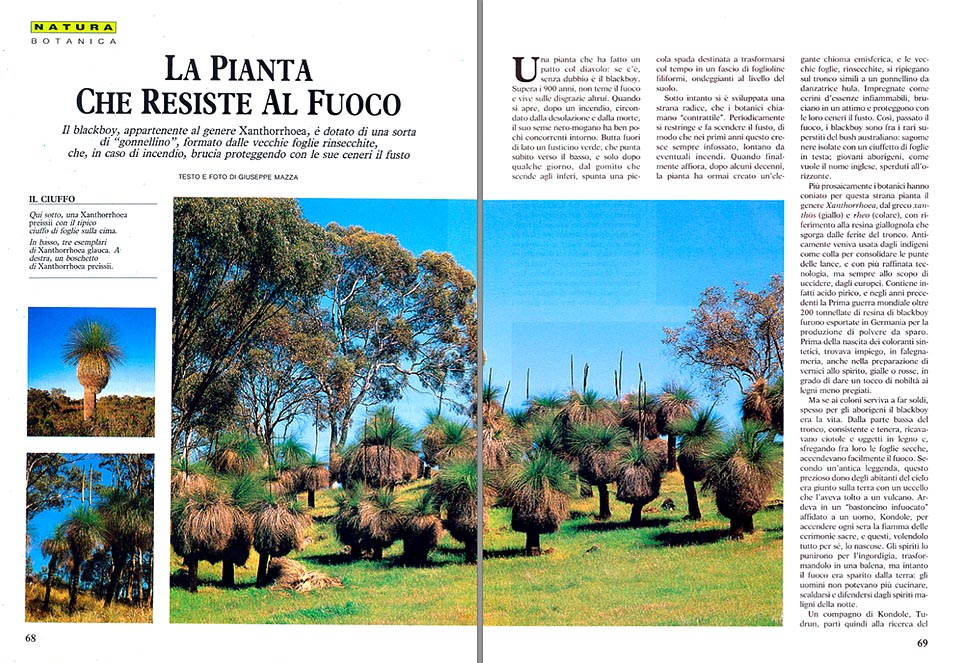

A plant which has reached an understanding with the devil: if it exists, then this is the Blackboy, no doubt.

It can live for more than 900 years, does not fear the fire, and lives on the bad lucks of the others.

When it opens, after a fire, surrounded by dreariness and death, its mahogany-black seed has very few competitors around. It throws out, on one side, a small green stem, which heads at once downwards, and only after some days, from the elbow which goes down to the inferior ovary, comes out a small spade, meant to transform, with the time, in a bundle of filiform little leaves, waving at the level of the soil.

Down below, in the meantime, a strange root, defined by the botanists “contractile”, has taken form.

It tightens periodically, and pushes down the stem, in such a way that during the first years, this grows up always sunken, distant from possible fires.

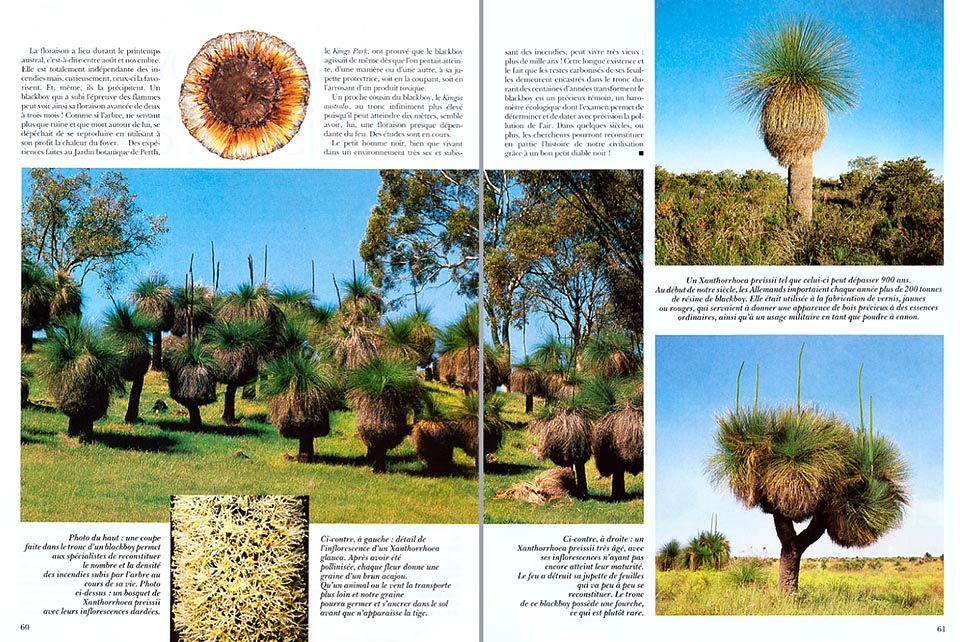

When, at last, it comes out, after some decades, the plant has by then created an elegant hemispheric foliage, and the old leaves, dried up, bend on the trunk, like a short skirt of a hula dancer.

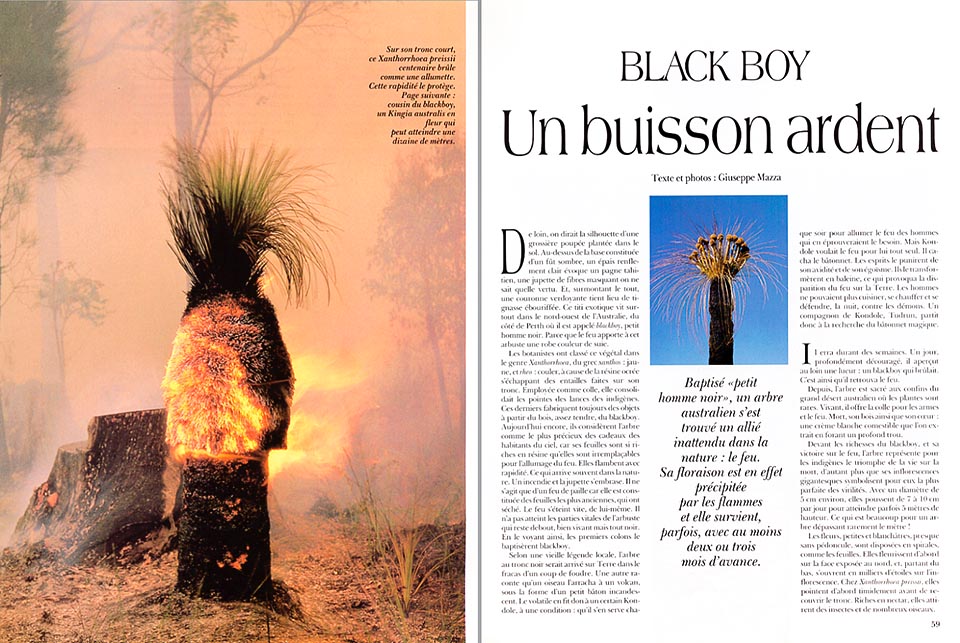

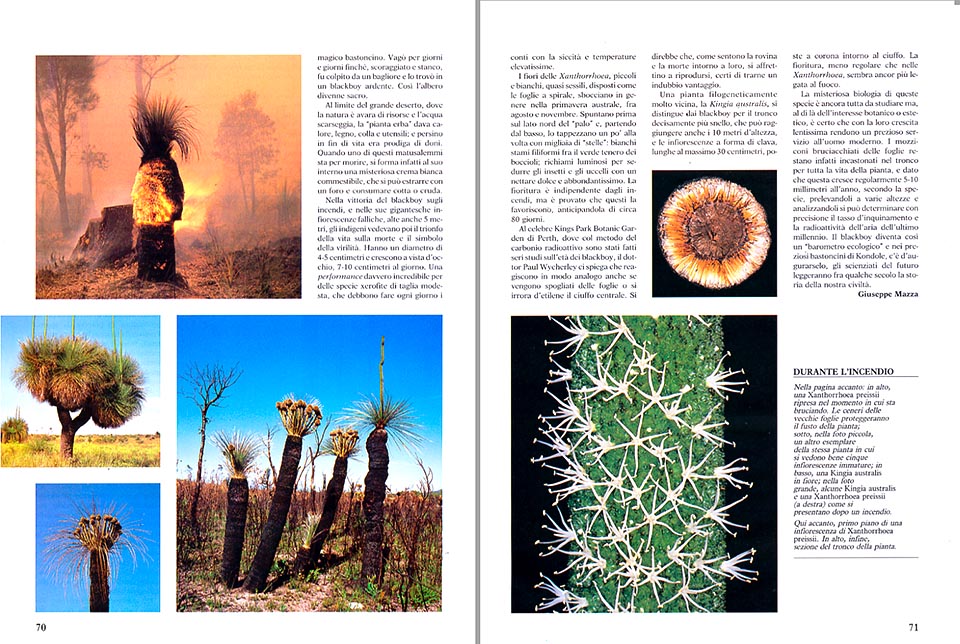

Impregnated, like vestas, of inflammable essences, they burn in a moment, and protect the stem with their ashes. So, once the fire is over, the Blackboys are between the very few survivors of the Australian bush: black lonely silhouettes, with a small tuft of leaves on the head; young aborigines, as the English name suggests, solitary in the horizon.

More prosaically, the botanists have coined, for this odd plant, the genus Xanthorrhoea, from the Greek “xanthos” (yellow), and “rheo” (to pour), referring to the yellowish resin which comes out from the wounds of the trunk.

It was used by the natives as a glue for consolidating the points of the lances, and with a more refined technology, but always for killing, by the Europeans. It contains, in fact, black powder, and during the years preceding the first world war, more than 200 Tons of resin of Blackboy were sent to Germany for the production of gun-powder.

Before the birth of the synthetic dyes, it was utilized, in carpentry, also in the preparation of spirit varnishes, yellow or red, able to confer a touch of nobility to the less prized woods.

But, if for the settlers it was good for making money, often, for the aborigines, the Blackboy was the life. From the lower part of the trunk, firm but tender, they were obtaining bowls and wooden objects, and, rubbing the dry leaves between them, they were easily able to light the fire.

After an old legend, this valuable gift of the inhabitants of the heavens, had come to the earth with a bird, which had taken it off from a volcano. It was burning in an inflamed “small stick”, entrusted to a man, Kondole, for lighting up, every evening, the flame of the holy ceremonies, and, wishing to keep it all for himself, he did hide it. The spirits punished him for the greed, transforming him in a whale, but, in the meantime, the fire had disappeared from the earth: the men could not cook, warm up, and defend themselves against the evil spirits of the night, any more.

A companion of Kondole, Tudrun, left then, looking for the magic small stick. He wandered for days and days, till when, discouraged and tired, was hit by a flash, and found it in a burning Blackboy.

So, the tree became sacred. At the limit of the wide desert, where nature is of few resources, the “grass tree”, was giving heath, wood, glue, and tools; and even when on the point of death, it was prodigal of gifts.

When one of these patriarchs is close to die, in fact, in its interior takes form a mysterious edible white cream, which can be extracted through a hole, and eaten raw or cooked.

In the victory of the Blackboy over the fires, and its gigantic phallic inflorescences, even five metres tall, the natives were seeing then the triumph of the life over the death, and the symbol of virility.

They have a diameter of 4-5 cm, and grow up before one’s eyes, 7-10 cm per day. A really incredible “performance”, for xerophyte species of such a modest size, which every day have to struggle against the drought and the very high temperatures.

The flowers of the Xanthorrhoea, small and white, almost sessile, placed coiled, like the leaves, generally blossom during the southern spring, between August and November. They sprout, first, on the north side of the “stake”, and starting from below, they cover it, a little at a time, with thousands of “stars”: white filiform stamens between the delicate green of the buds; luminous calls for seducing insects and birds, with a sweet and very abundant nectar.

The flowering does not depend on the fires, but it is proved that these ones help it, anticipating the flowering of about 80 days.

In the famous Kings Park Botanic Garden of Perth, where, with the method of the radio-active carbon, they have done serious studies on the age of the Blackboys, Dr. Paul Wycherley explains me that they react in an analogous way also if they are deprived of the leaves, or if the central tuft is sprinkled with ethylene.

We might say that, as soon as they feel ruin and death around them, they hurry to reproduce, sure to profit of them.

A very close, phytogenetically, plant, the Kingia australis, distinguishes from the Blackboy for its more slender trunk, which can reach the ten metres of height, and the club-shaped inflorescences, long, at the most, 30 cm, placed like a crown around the tuft. The flowering, less regular than in the Xanthorrhoea, looks even more connected to the fire.

The mysterious biology of these species is still all to be studied, but beyond the botanical and aesthetic interest, it is sure that with their very slow growth, they give the modern man a precious service.

The scorched stubs of the leaves remain, in fact, set in the trunk, for the whole life of the plant, and, as it grows, regularly, of 5-10 mm per year, depending on the species, taking them off at different heights, and analyzing them, we can determine with precision the rate of pollution and the radio-activity of the air during the last millennium.

The Blackboy becomes in this way, an “ecological barometer”, and in the precious small sticks of Kondole, we have to wish this to ourselves, the men of science will read, in some centuries, the history of our civilization.

SCIENCES ET NATURE + SCIENZA & VITA NUOVA – 1991