Ancestors of geraniums come from South Africa. History of these plants that in only three centuries of cultivation have developed an impressive number of hybrids. The original kinds, called “botanic”, are now in fashion in Mediterranean climates.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

What is the reason for the great success of geraniums?

Roses are cultivated since millennia, geraniums since only three centuries, but, practically, they stand without rivals, on terraces and balconies.

Rustic, resistant to the sultry weather, also when we forget to water them, they are contented of a little of earth, and overflow from the sills with spectacular cascades and very rich flowering, almost without respite. They grow up easily and quickly.

Try to detach a small branch, and inter it in a mixture of peat and sand: it will start again, at once, vigorous, reproducing exactly the same characteristics of the parent.

So, if, by chance, in their immense horticultural population, comes to life an Einstein, a Brigitte Bardot, or a Carmen Russo, it is sufficient to make cuttings, and in short time, one becomes a thousand, a thousand one million: the seasonal sale of a big producer of geraniums.

And if, due to a lucky mutation, strange white strips come out on the red petals, in the time of few years, half of the balconies will overflow of white and red strips, because man loves new things, and the geraniums, besides transforming housewives and bankers in floriculturists of success, give satisfaction quickly and at low cost to his need for the “different”.

By sure, almost all the plants reproduce by cutting, it is a privilege of the Green World, that most of the animals have lost, with the chlorophyll, millions of years ago, but the geraniums root, without any problem, in 2-3 weeks, and after one month, they are already in bud on the counters of the florists.

To give those miracles of beauty and fantasy of which they are capable, the exotic orchids need a warm greenhouse and endless attentions; geraniums give everything at once, also to the beginners; and, exploiting with ability their fanciful genes, the professionals have obtained incredible double flowers, resembling to roses and huge petals, variegated, which recall the azaleas.

“The cultivars present in the market”, Prof. J.J.A. Van Der Walt, the greatest authority in this field, explains to me, “present, often mixed up, the characters of at least 20 botanical geraniums”.

But these ones are almost impossible to be found: the origins hide, as usual, under the beginnings, and for knowing the ancestors of our domestic geranium, we have to go to South Africa, in the Cape Province.

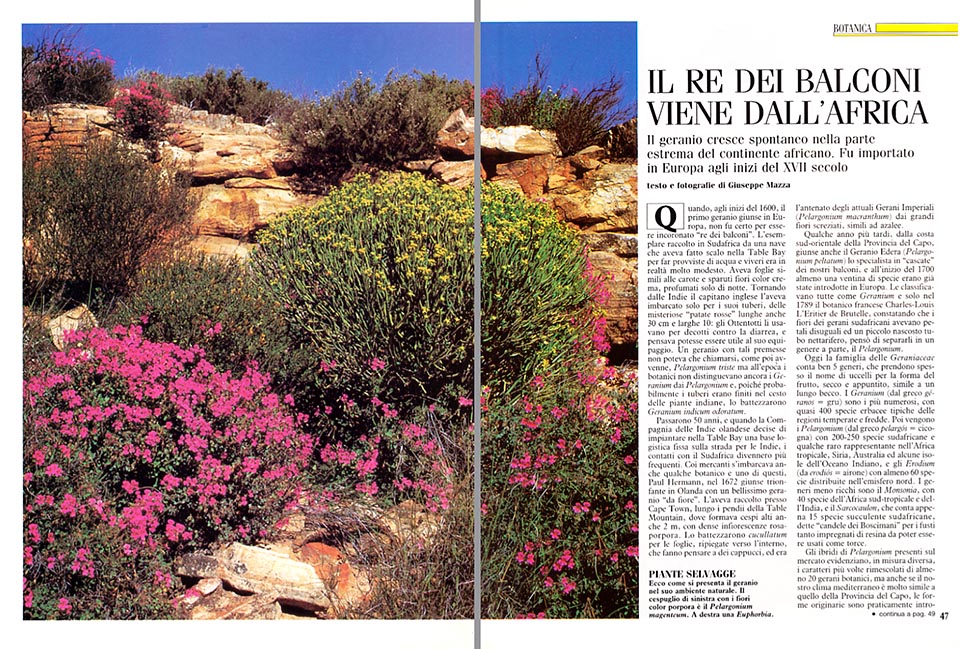

Here, we discover an almost Mediterranean climate, and struck by a crowd of geraniums with strange flowers and leaves, very different from the cultivars we are used to, we wonder immediately, astounded, why they do not grow up also in our countries.

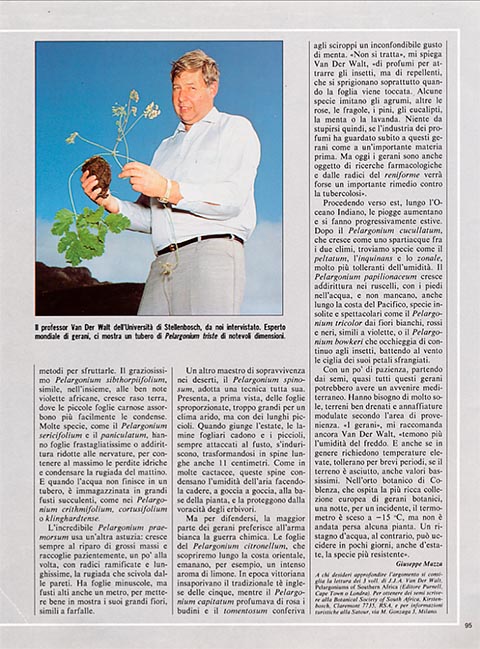

“The reason,” Van Der Walt explains to me, in his office at the University of Stellenbosch, the most ancient in South Africa, “is, incredibly, only historical”; and he engages, with botanical zeal, in a long and very tormented Pelargonium Story.

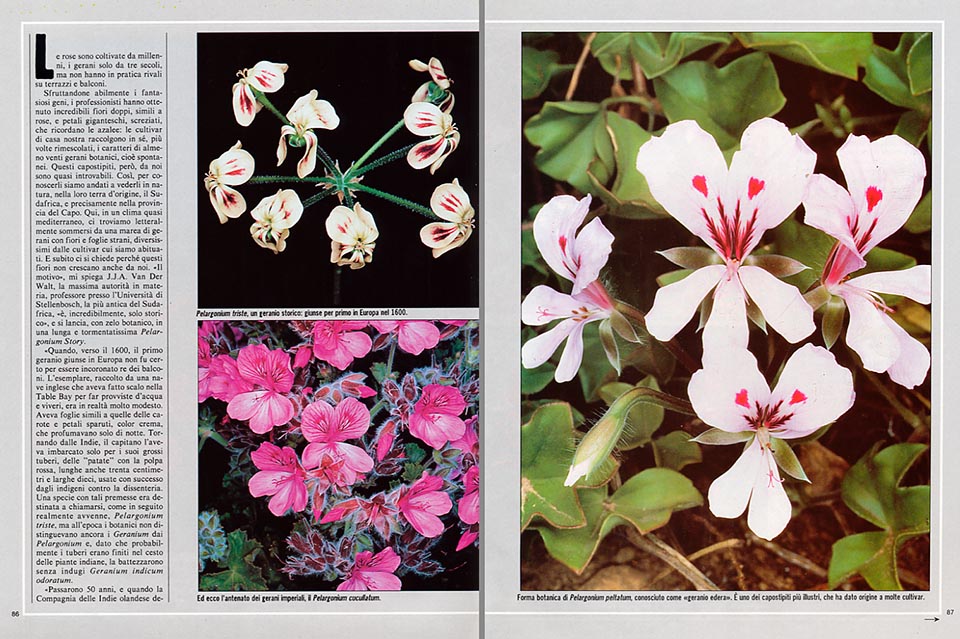

When, around 1600, the first geranium reached Europe, it was not, by sure, for being crowned as king of the balconies.

The specimen picked up by an English vessel which had made a call in the Table Bay for loading water and provisions, was, in reality, very modest. It had leaves similar to carrots, and lean petals, cream coloured, which were perfumed only during the night.

While coming back from the Indies, the master had embarked it only for its big tubers, “potatoes”, with a red pulp, long even 30 cm and 10 wide, utilized, successfully, by natives against the diarrhoea.

A species with such premises, could not be called otherwise, as it happened, than Pelargonium triste, but at that time botanists were not yet differentiating the Geranium from the Pelargonium, and seen that probably the tubers had ended up in the basket of the Indian plants, they christened it, without delays, Geranium indicum odoratum.

Fifty years elapsed, and when the Dutch East India Company decided to occupy the Cape of Good Hope, and settle there a logistic base on the route to Indies, the contacts with South Africa became more frequent. Also some naturalists were joining the vessels together with the traders, and one of them, Paul Hermann, came back, triumphant, to Holland, in 1672, with a very beautiful “florists’ geranium”.

He had picked it up close to Cape Town, along the slopes of the Table Mountain, where it formed tufts tall even 2 metres, and thick pink-purple inflorescences. They called it “cucullatum”, due to the leaves, folded towards the interior, similar to cowls, and this was the ancestor of the present Royal Geraniums (Pelargonium macranthum), with great variegated flowers, similar to azaleas.

A few years later, from the south-east coast of the Cape Province, came also the “Ivy Geranium” (Pelargonium peltatum), the specialists in the cascades of our balconies, and, by the beginning of 1700, about 20 species had been already introduced to Europe.

They went on in calling them Geranium, like our country or mountain geraniums, and only in 1789, the French botanist Charles-Louis L’Eritier de Bretelle, had the good idea to place them in a particular genus, the Pelargonium, seen that, unlike their European “poor relatives”, they had unequal petals and a small, hidden, nectarean duct.

But, at this point, the appellation of “geranium”, had become of common usage, and few authors, talk today, courageously, of “pelargoniums”.

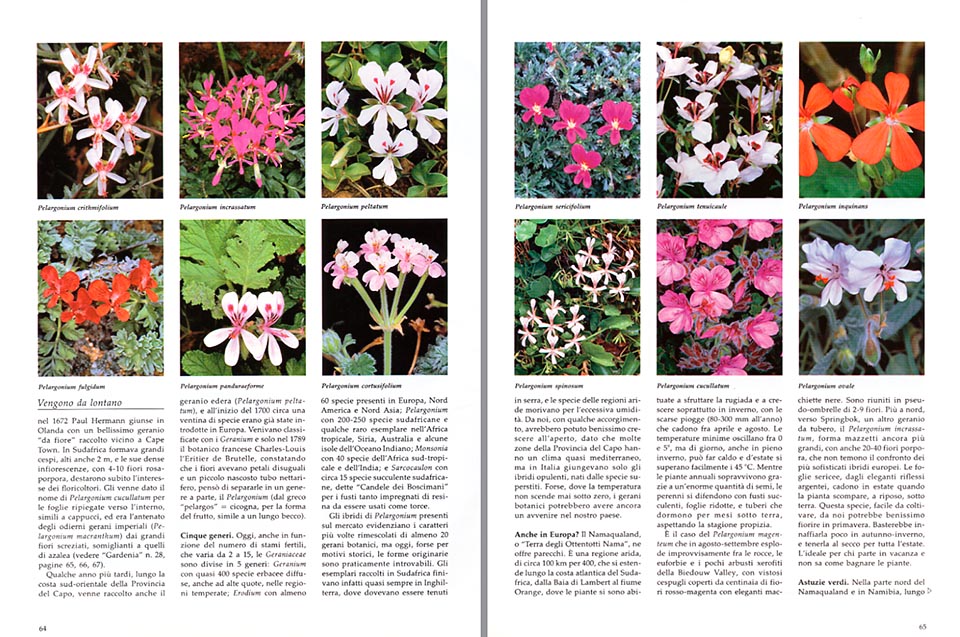

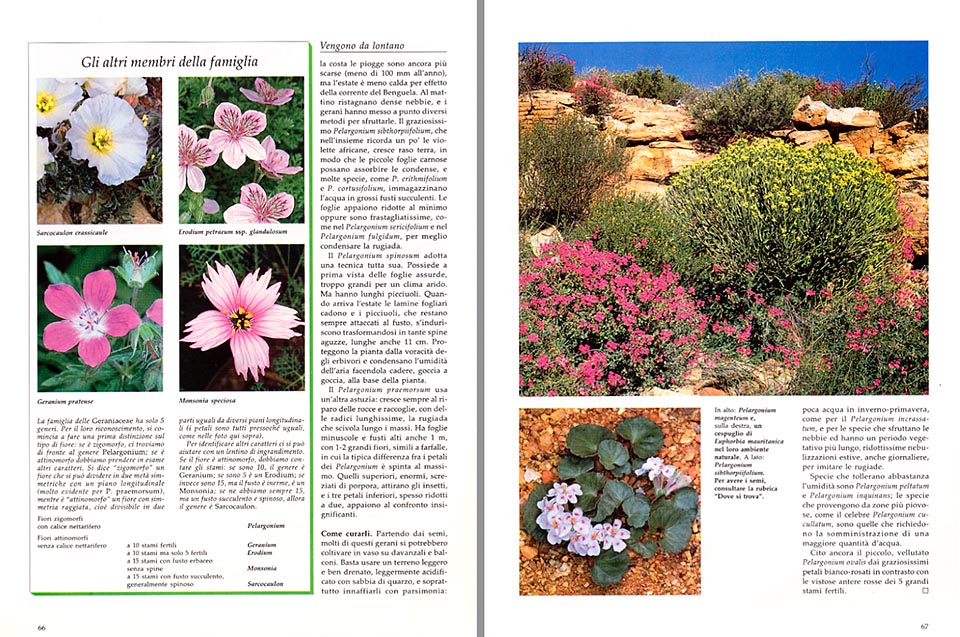

So, until further orders, the family of the Geraniaceae counts 5 genera, with names mostly borrowed from the birds, due to the form of the fruits, dry and pointed, similar to long beaks.

The Geranium (from the Greek géranos = crane), are the most numerous, with almost 400 herbaceous species typical of the temperate and cold regions.

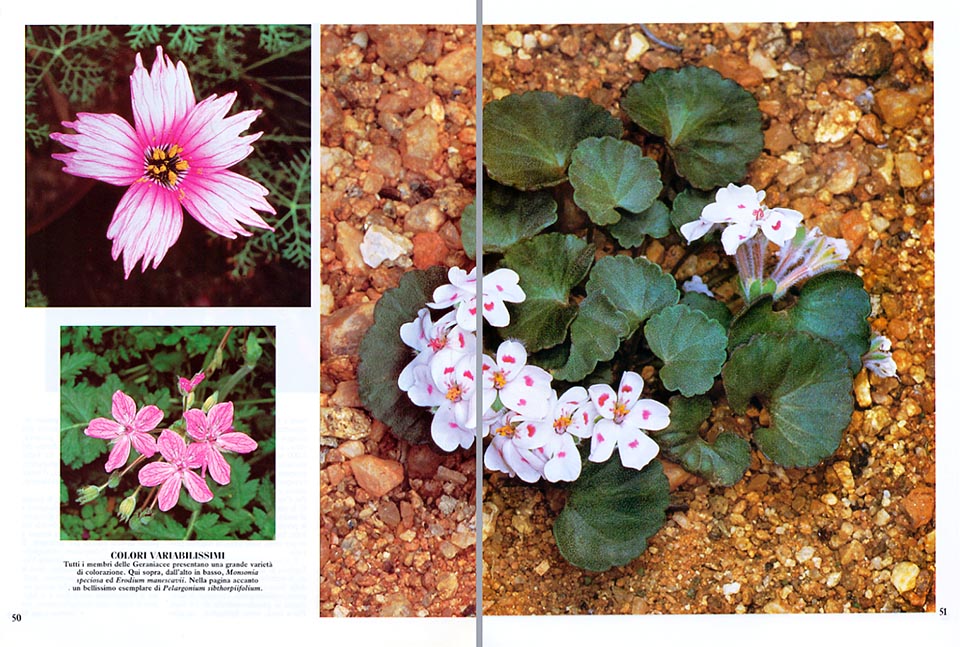

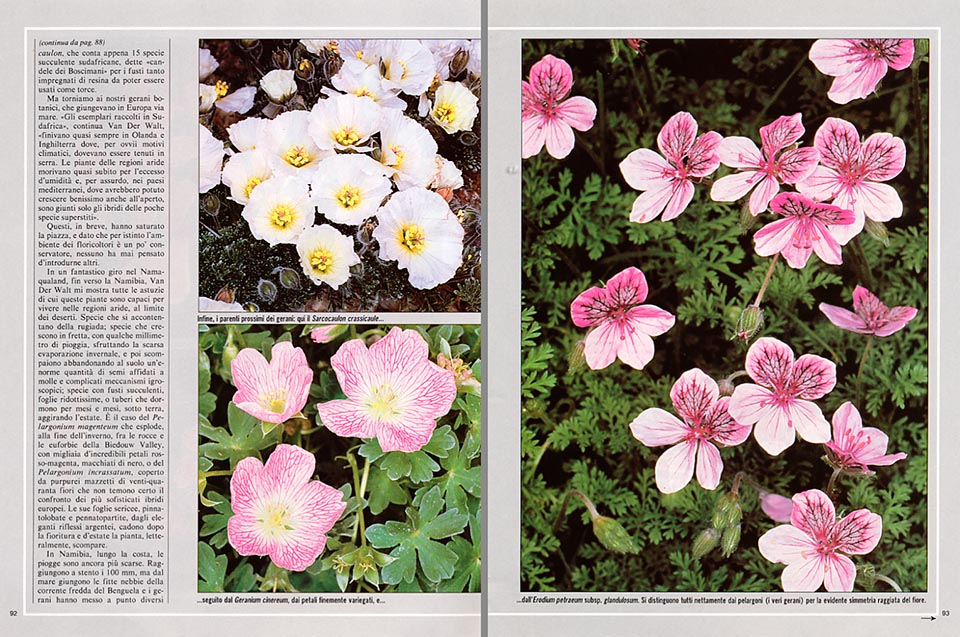

Then come the Pelargonium (from pelargos = stork), with 200-250 South African species and some rare specimen in tropical Africa, Syria, Australia and few islands in the Pacific Ocean, and the Erodium (from erodios = heron), with about sixty species spread in the northern hemisphere.

The less rich genera are the Monsonia, with 40 species, of south tropical Africa and India, the Sarcocaulon, which numbers only 15 succulent South African species, called “Bushmen Candles”, for the stems so much impregnated of resin, to be used as torches.

But let’s go back to our botanical geraniums, which were coming to Europe by vessel.

“The specimen found in South Africa,” Van Der Walt continues, “were ending almost always to Holland and England, where, due to obvious climatic reasons, they had to be kept in greenhouse. The plants of the arid regions were passing, almost immediately, away, due to the excess of humidity, and, absurdly, in the Mediterranean countries, where they might have been growing very well, also in open air, have come only the hybrids of the few surviving species.

These, in short time, have saturated the market, and seen that, by instinct, the environment of the floriculturists is somewhat conservative, nobody has ever thought to introduce other ones.

Are missing to the call all early geraniums, with winter growth, which hibernate in summer and therefore might be abandoned, without any problem, without water, even in the warmest balconies, at the moment of departures for the vacations.

During a fantastic tour in Namaqualand, up to Namibia, Van Der Walt shows me all the ruses these plants are capable of, for living in arid regions, close to the border of the deserts. Species which content themselves of the dew; species which grows up quickly, with just some millimetres of rain, exploiting the scarce winter evaporation, and then disappear, leaving on the ground a huge quantity of seeds entrusted to springs and complicated hygroscopical mechanisms; species with succulent stems, very reduced leaves, or tuners, which sleep for months and months, under the ground, avoiding the summer.

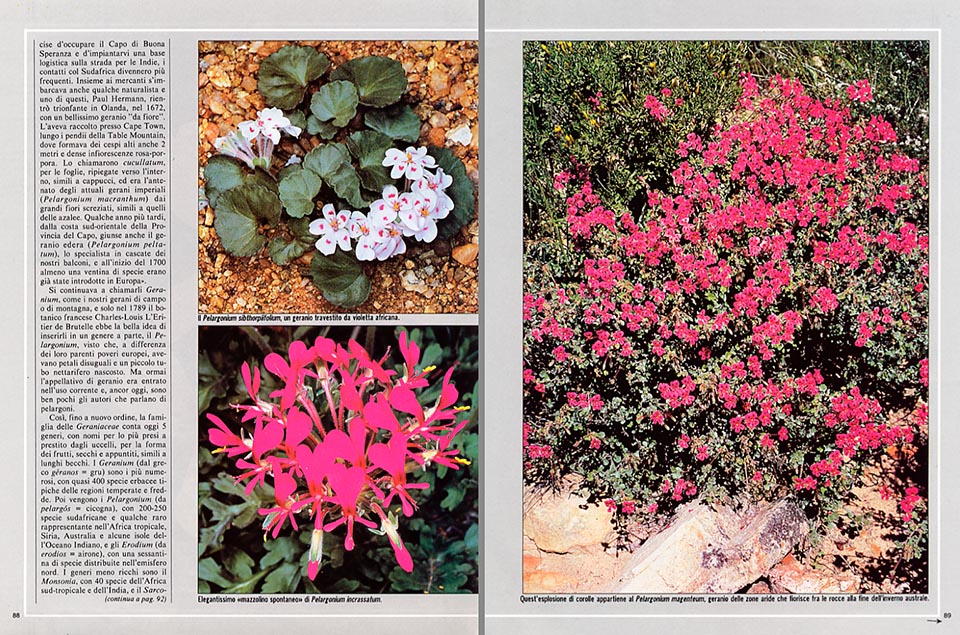

This is the case of the Pelargonium magenteum, which explodes, by the end of winter, between the rocks and the euphorbias of Biedouw Valley, with thosands of incredible red magenta petals, spotted of black, or of the Pelargonium incrassatum, covered of small purple bunches of 20-40 flowers, which are not afraid for the comparison with the more sophisticated European hybrids.

Its silky leaves, pinnatilobate and pennatopartite, with elegant silvery reflections, fall after the flowering, and in summer, the plant, literally, disappears.

In Namibia, along the coast, the rains are even more scarce. They reach, not without effort, the 100 mm, but from the sea come the thick fogs of the cold stream of Benguela, and the geraniums have realized several methods to exploit them.

The most charming Pelargonium sibthorpiifolium, similar, in the whole, to the well known African Violet, grows close to the soil, where the small pulpy leaves absorb more easily the condensation. Its stomata, the small “mouth”, with which the plants catch the carbon dioxide, and disperse the water, are not, as usual, on the upper side, but on the other, almost touching the ground, where the evaporation is lesser.

Many species, such as the Pelargonium sericifolium and the paniculatum, have very indented leaves, or even reduced to the nervations, in order to repress at the maximum the water losses and condensate the morning dew.

And when the water does not end up in a tuber, it’s stored in large succulent stems, like in the Pelargonium crithmifolium, cortusifolium or klinghardtense.

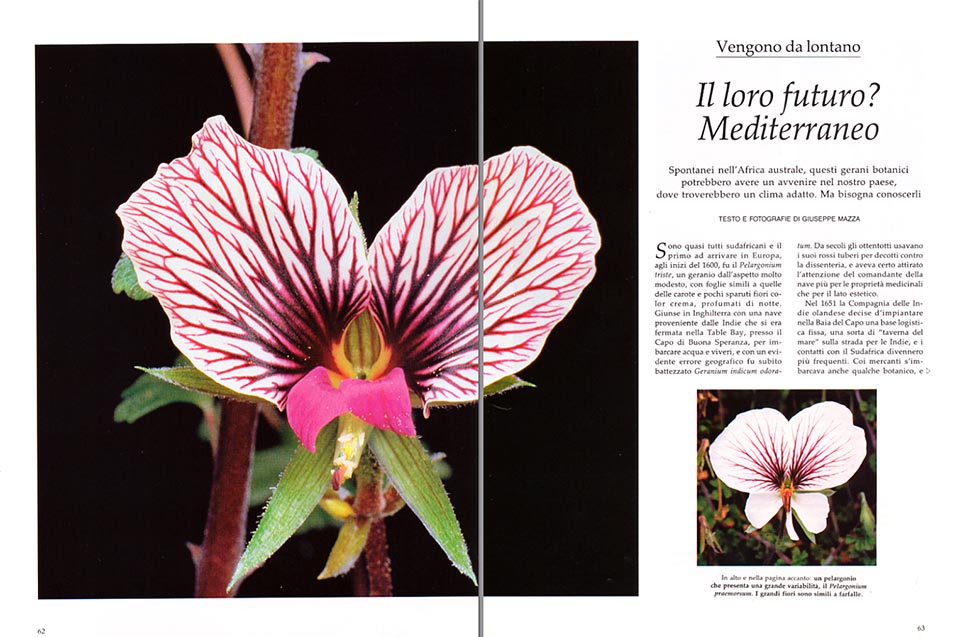

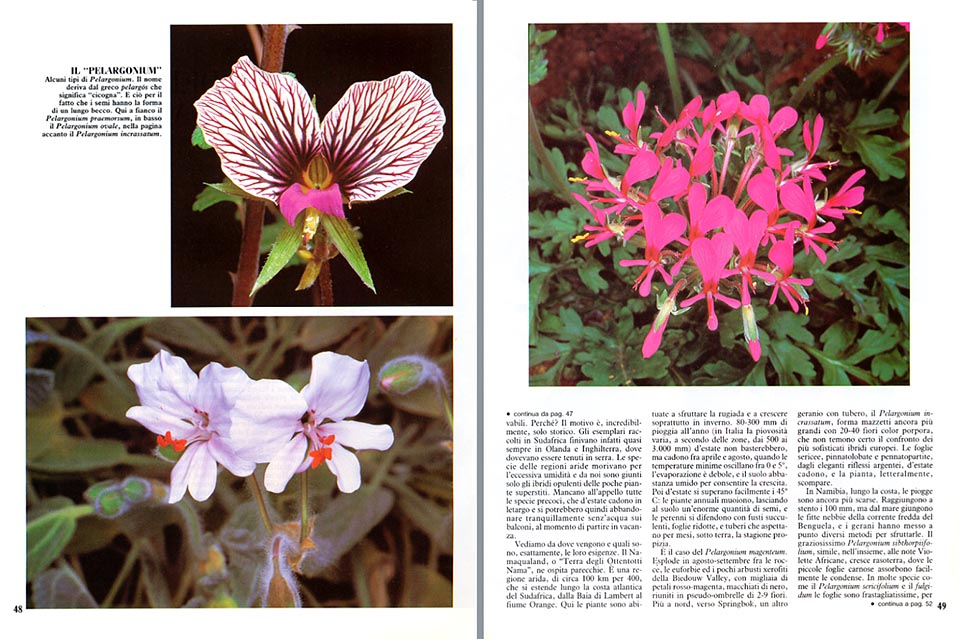

The incredible Pelargonium praemorsum utilizes another ruse: it grows always at the shelter of great stones and collects patiently, a little at a time, with ramified and very long roots, the dew which slides along the sides. It has tiny leaves, but stems tall even one metre, in order to display well its large flowers, similar to butterflies. Here, the typical difference between the petals of the Pelargoniums is pushed to the maximum: the upper ones, enormous, variegated of purple, have the duty of attracting the insects, and the three lower ones, often reduced to two, appear, in comparison, negligible.

Another master of survival in the deserts, the Pelargonium spinosum, adopts its own technique. It shows, at first sight, some absurd leaves, too big for an arid climate, but having long petioles.When the summer comes, the foliar laminae fall and the petioles, always stuck to the stem, harden, transforming in thorns, long even 11 cm. Like many cactaceae, they condensate the humidity of the air, making it to fall, drop by drop, to the base of the plant, and protect it from the voracity of the herbivores.

But to defend themselves, most of the geraniums prefer the chemical war to the cold steel.

The leaves of the Pelargonium citronellum, which we shall discover along the eastern coast, emanate, for instance, an intense fragrance of lemon. During the Victorian Age, they were flavouring the traditional English five o’clock tea, whilst the Pelargonium capitatum was perfuming of rose the puddings and the tomentosum was giving to the syrups an unmistakable taste of mint.

“It is not matter”, Van Der Walt explains to me, “of perfumes for attracting the insects (the pollinators, flies with a long trunk, are seduced by the nectar and by the converging drawings of the petals), but of repellents, which exhale, especially when the leaf is touched.”

Some species imitate the citrus fruits, other the roses, the strawberries, the pines, the eucalypts, the mint, or the lavender. It is not astounding, therefore, if the perfume industry has looked immediately to these geraniums, like an important raw material. Since years, in the island of Mauritius, they cultivate a particularly successful hybrid, with a very intense aroma. They have called me for an advice about its parents, and after having analysed the essential oil and the chromosomes, I have concluded, with a colleague, that it is matter of a hybrid of radens and capitatum.

But nowadays, the geraniums are also object of pharmacological researches, and from the roots of the reniforme, they hopefully will get an important remedy for the tubercolosis.

Proceeding eastwards, along the Indian Ocean, the rains increase and progressively, become summery. After the Pelargonium cucullatum, which grows like a watershed between the two climates, we find species like the peltatum (with a very ample distribution from the south east of the Cape Province up to the north of Transvaal), the inquinans and the zonale, very much tolerant to the humidity.

The Pelargonium papilionaceum grows up, even, in the brooks, with the feet in the water, and there are, also along the Indian coast, unusual and spectacular species, such as the Pelargonium tricolor, with white, red and black, resembling to violets, flowers, or the Pelargonium bowkeri, which makes eyes continuously at the insects, twinkling the cilia of its incredible fringed petals to the wind.

With some patience, starting from the seeds, almost all these geraniums might have a Mediterranean future.

They need much sun, well drained soils, and watering modulated depending on the place of origin. The western species, with winter growth, require daily nebulizations, from the end of winter to the blooming, and a light soil, acidified with sand of quartz; the eastern noes, with summer growth, a more consistent soil and more abundant watering, in summer, like the common balcony hybrids.

“The geraniums”, Van Der Walt recommends again to me, “fear more the humidity than the cold. And even if, generally, they need high temperatures, they tolerate, for short periods, if the soil is dry, also very low values.”

In the botanic orchard of Koblenz, which gives hospitality to the richest European collection of botanical geraniums, one night, due to an accident, the thermometer went down to -15 °C, but not even one plant was lost. A stagnation of water, on the contrary, can kill in a few days, even in summer, the more resistant species.

GARDENIA + SCIENZA & VITA + NATURA OGGI – 1989

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within the GERANIACEAE family please click here.