Family : Giraffidae

Text © DrSc Giuliano Russini – Biologist Zoologist

English translation by Mario Beltramini

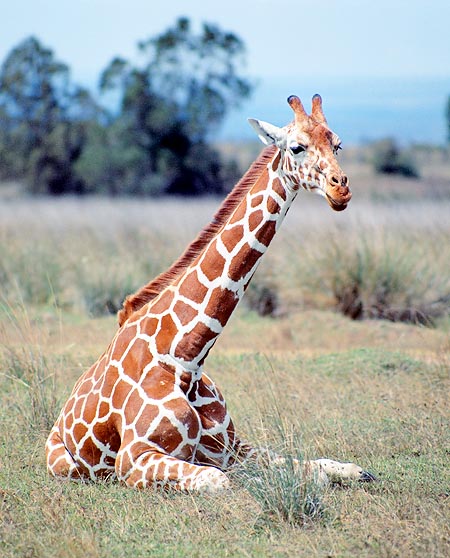

Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata © Giuseppe Mazza

The Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis Linnaeus, 1758) is an Artiodactyle (Artiodactyla), ruminant (Ruminantia), belonging, with the Okapia (Okapia johnstoni), to the family of the Giraffids (Giraffidae).

The name of the genus appears to come from the Bantu dialect “Zahraf”, which means “docile animal”, whilst that of the species comes from a text by Cicero, who talks about an odd animal having the characteristics of a camel or of a leopard.

Nowadays, the biologists agree in affirming that there are 9 subspecies of giraffes, which may be distinguished, thanks to the phenotype-colour-morphology of the coat, and which should be the:

Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata (Somali Giraffe)

Giraffa camelopardalis angolensis (Angolan Giraffe)

Giraffa camelopardalis antiquorom (Kordofan Giraffe)

Giraffa camelopardalis tippelskirchi (Masai Giraffe)

Giraffa camelopardalis camelopardalis (Nubian Giraffe)

Giraffa camelopardalis rothschildi (Baringo Giraffe)

Giraffa camelopardalis giraffa (South African Giraffe)

Giraffa camelopardalis thornicrofti (Thornicroft Giraffe)

Giraffa camelopardalis peralta (Nigerian Giraffe)

The neck of the giraffe, varying among the individuals and the subspecies, even reaches the 2 metres of length, and can lead the non-biologist to hypothesize that it is formed by much more than the seven cervical vertebrae which compose the neck of humans and of all other placentate Mammalia, actually, the number of the cervical vertebrae is the same (always 7), what changes is the length of each vertebra which is bigger.

In the giraffes there is a clear problem of circulation physiology due to the fact that when in position of erect neck, the brain is about 3 metres higher than the heart and when the animal bends its head, it reaches a difference in height of two metres from the heart. This undeniably causes remarkable efforts in order to allow the blood to always reach the brain which electively need a constant physiological input of the same, for their nutrition and oxygenation.

For this purpose, the evolution has managed to create a triple control system, which maintains constant in a sure manner the blood pressure systemic to physiological values, as well as having modelled the dimensions of the heart which reach, from the pointed apex to the base of the myocardium the length of 60 cm!

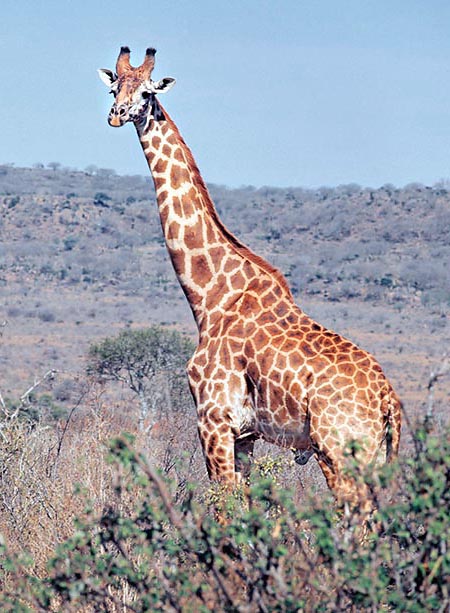

Giraffa camelopardalis rothschildi © Giuseppe Mazza

Thanks to a particular (anatomical-histological) adaptation of the internal carotid artery, to the presence of valves in the jugular veins and on a vascular system called Rete mirabile which stabilizes the blood pressure in the cerebral vessels (expanding and contracting the small arteries which constitute it), the homeostasis of the blood pressure is assured, so the animal will not lose (for jerks of the blood pressure) consciousness when will raise its head and when, also quickly, will low down the same.

Zoogeography

Endemic of sub-Saharan Africa (from Somali, Angola, to South Africa).

Habitat-Ecology

Savana.

Nutrition

Has both nocturnal and diurnal habits for what nutrition is concerned, it feeds of sprouts, fruits, pods and leaves (in particular Acacia’s), which it pulls out with the prominent lips, after having grasped the branch with its long and seizing tongue.

Morpho-physiology

The characteristic is a neck which can be two metres long, as a whole the male animal can reach the 5-5,7 metres of height and weigh from 800 to 2000 kg. The females are smaller and can reach the 4-4,5 metres of height and weigh 500-1200 kg.

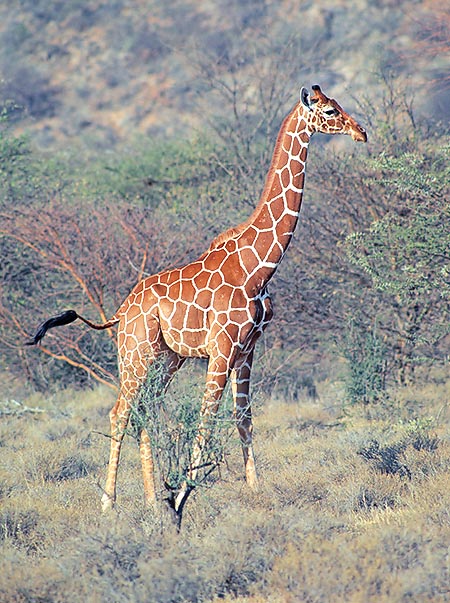

The mantle has a variegated morphology, or brown dots on yellow background such as in the Giraffa camelopardalis camelopardalis, or with darker (brown) dots surrounded by a white line forming a net on yellow background like in the Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata, further small differences in other subspecies.

Provided with excellent eyesight, it is one of the few mammals (like the pongid primates and human beings) able to distinguish the colours, also the hearing and the sense of smell are well developed. The eyes have robust lids which defend it during the nutrition from thorns and twigs. In the end, there are two not much big (lance-shaped) ear pinnae, well developed on a thin and elegant head with an elongated muzzle.

On the head is located a variable number (from subspecies to subspecies) of horns, well different from the bovids’ (which are hollow) because sustained by a bony protuberance always covered by skin, with presence of irregular tufts of hair. Well developed limbs, very long, massive trunk, short if compared with the neck and leaning backwards, presence of a long tail (it can be even 1 metre long), ending with a compact tuft of hair.

The giraffes horns are equal and unequal, inserted in the front or on the nasal bone © Giuseppe Mazza

During the sixties of the XX century, the zoological biologists Mrs. Dag Innis and C.A. Spinage have deeply studied the structure of the skull of the giraffe.

The horns, which are permanently covered by hairs, develop from ossification centres under the skin and fuse with the underlying bone.

The two bigger horns are inserted into the parietals; the median horn, unequal, on the frontal and on the nasal bones.

There are often other smaller horns, equal, on the occipital region and over the eyes; furthermore, there are also extensions of the median horn.

As the animals age, more bone is depositing, and this includes the blood vessels in tubular cavities, unlike what happens in the deer, whose blood vessels are placed out from the bone, under the velvet of the antlers.

In the old males, the “exostoses” (bony protuberances), are much extended and give the skull a knobby appearance.

C.A. Spinage hypothesized that this conformation is to be correlated with the giraffes’ habit of rubbing the own necks each other, and that the secondary ossification serves for protecting the blood vessels from possible damages, during the most intense phase of this behaviour.

He observed that a male provided with a skull weighing 11 kg, is considerably advantaged in the struggling, in respect of a male having a 7 kg skull.

The exostoses are not a consequence of the mechanic trauma, but are a “secondary sexual character”, of genetic origin, and therefore is not and answer to a lesion or to a stimulation following the struggle.

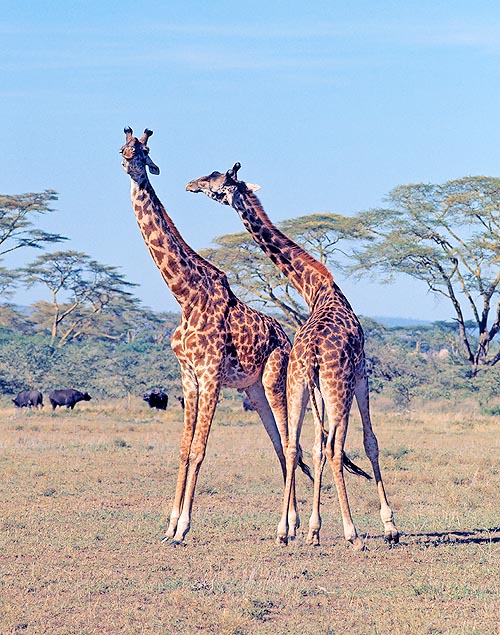

Gentle butts for the dominancy between Masai giraffes males © Giuseppe Mazza

In many, but not all, ruminants, the liver has no gallbladder. Many giraffes, in the past, were dissected by the biologists, but the doubt if they were having or not the gallbladder.

Finally, the biologist A.J.I. Cave did solve this question in 1950.

For a curious incident, the giraffe examined by the zoological biologist Owen in 1838, the first to be dissected in Europe by a zoological biologist (before this was done only by curious hunters, who did not give any importance to the comparative Anatomy), had a big gallbladder, whilst the following biologists had been unable to find any in the specimens they had examined.

A.J.I. Cave found that a rudimental gallbladder is normally present in the foetus, but that, usually, the same gets a regression and a physiologic involution, and so it is absent upon the birth; as, on the contrary, had nor occurred in the abnormal specimen of Owen who, for more than a century, was cause of much confusion.

Ethology and Reproductive Biology

The giraffes are docile animals, which usually have a non aggressive character.

The disposition of the spots is detectable like the fingerprints in the man, and the zoological biologist Foster, used them during his studies in the wild, during the seventies of the last century, for following the displacements and the behaviour of the single animals; this great biologist was even capable to recognize some specimens from photographs casually shot more than ten years before. The biologists (zoologists, ethologists), must often utilize methods of elaborated and difficult, for recognizing single individuals, but with the giraffes this is not necessary.

Among the many African ungulates, the giraffe (along with the black and white rhinos, the zebras, the elephant, the hippo and the Cape buffalo) is one of the few which has been studied on the field in a complete way by zoological biologists having serious academic preparation; as a consequence, we have a great quantity of data about its life, its habits and its behaviour.

The biologist lady, Mrs. A. Dagg Innis, has studied in the first half of the sixties of the XX century, the life of the Giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis and the subspecies Giraffa camelopardalis giraffa), in the low Velt of eastern Transvaal, in an area of thicket formed by deciduous latifoliate, in part thick and in part more open and similar to a park.

The animals ate the foliage of a great number of different types of trees, but especially those belonging to the order of the fabaceae and were more selective, when the trees were fully covered by leaves.

Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata. The males love the woody areas © G. Mazza

In a following study, the same Mrs. Dagg Innis, proved that there was no correlation at all among the preferences of the giraffe and the ashes, the crude extract in ether and the crude contents I proteins of the analyzed foliage. Such preferences are possibly based mainly on the taste… it seems right to me that also the giraffes, as is our case, may be greedy.

When the giraffes eat the foliage, they may reach even 6 m tall points, where it may be seen a marked line of grazing of the tops of these trees.

In Kenya, the biologist Foster has proved that the trees exceeding this height were grazed in form of a “watch glass”, whilst the lowest ones in form of “honeycomb”. He advanced the hypothesis (still now under study) that the presence of trees of the first type should indicate that in the past the giraffe had been absent for some time from the examined location, seen that, where it is always present, the trees cannot grow beyond the height of the honeycomb ones.

Mrs. D. Innis remarked that “it was interesting to see all the taller giraffes nourishing of the choice tree”, whilst the lower ones did nourish of the close bushes, which is an example of alimentary organization.

The giraffes spend most of the day eating and chewing the bolus, not only while resting, but also while walking.

As an average, a giraffe chews each morsel 44 times, at the rhythm of one chewing per second.

As said before, they are object of the attentions of the ox-peckers and of the cattle egrets which nourish of the ticks parasitizing them, in particular under the belly and in the genitals areas, where the hair is thinner.

Furthermore, also the giraffes keep themselves busy, scratching their stomach, with a back and forth movement over bushes and rocks up to 180 cm tall.When, on the other hand, the ticks install on the back, for getting rid of them, they move backwards in the thick “bush”.

The giraffes may live in herds of even 70 individuals. It is in any case matter of very unstable associations, because the single males often aggregate and then go away, and there is not a specific “leadership”, even if in every mixed herd there is always a big male which usually is the dominant.

Apart the mixed groups, there are also herds formed only by adult and sub-adults males, separated or united. And there are always a certain number of solitary males looking for females in oestrum.

The structure of a giraffes herd is socio-biologically unstable © Giuseppe Mazza

The mating period varies from region to region, but usually takes place from July to September.

A courting ritual does not exist. Usually, the male approaches a female and leaks its tail, or takes the same between the lips.

While ignoring it ostensibly, the concerned female begins to urinate and the male collects part of the urine on the lips or on the tongue and tastes it.

Then, it raises the head, and, mouth shut, typically grinds the teeth if the female is in oestrum, the famous “Flehmen response”.

From the information of Mrs. Innis, it seems that the male, before the mating, assumes a characteristic position, with rigid forelimbs.

The pregnancy gestation of the female is of about 14-16 months, the delivery takes place with the female standing, and spreading the four legs at the moment of the expulsion of the only one cub which is delivered (a twin delivery may happen quite rarely), who has an average weight of 50-70 kg and may be even two metres tall.

Already after few hours, the small newborn is able to walk close to the mother, suckling frequently. The sexual maturity is reached by both sexes around the third year of life. In the herds of males only, there is a strange manifestation of love games.

The fauna biologist M.J. Coe, who has studied carefully, from 1966 to 1969 this behaviour in the Kenya giraffes (the species Giraffa camelopardalis as well as the subspecies Giraffa camelopardalis tippelskirchi), describes it as a variable behaviour.

Watering is a risky moment for this Giraffa camelopardalis tippelskirchi © Giuseppe Mazza

Two males may stand one in front of the other and shake the head in such a way to rub each other’s neck; or they place head-tail, and swing the head giving rather strong shots with the short horns, in the sides and the loins. This second behaviour is often followed by the “Flehmen response” and by the erection of the penis.

Mrs. Dagg Innis has found an analogous behaviour in the Transvaal giraffes and has been the first one to describe it.

These biologists think that this homosexuality forms an important mechanism of socio-sexual liaison, by means of which a hierarchy between the males takes form, whilst the exchange between the strictly masculine groups and the mixed ones, helps to maintain the contact between the sexes of this polygamous animal.

In Transvaal, Mrs. D. Innis has found that the males were more numerous than the females.

In Kenya, on the contrary, Foster has noted the contrary, but has concluded that these are not remarked because they tend to live in the forests more than the females and the young, who, on the contrary, love the open areas. The males might even be less, because they are more vulnerable to the predators when in a forest, where the capacity to scan the surrounding environment is reduced.

The home-range of the giraffes has not yet been determined, but some biologists deem, from some indications they obtained on the field, the females and the young cover an area of 50 square km. Neither the males, nor the females do defend the territory.

Not only the structure of the herd is socio-biologically unstable, but the same is the case also for the bond within mother and son, as it was observed by Foster as well as by Mrs.Innis.

Giraffa camelopardalis tippelskirchi with an already 2 m tall newborn © Giuseppe Mazza

The young begin to nibble the leaves since their first week of post-natal life, and, moving away from the parents they join groups of other young; often, a little later, they come back to the mother or move towards another group. And then, the fact that often the mothers are seen going around without progeny, made Foster to conclude that many newborn die during the first days of autonomous life, without leaving any trace, probably victims of predators and of their own inexperience.

The structure of the adult herd is even more casual than the relationship between parents and progeny. Foster did note that in all the herds might be observed, sooner or later, the presence of some different individuals.

The sub-adult males join the groups of bachelors during the third year of life, and do not go around alone, till when they are not sexually mature.

None of the here mentioned zoological biologists has ever registered some vocal signal of communication. At the most, they have heard a snort of warning. It seems that the visual communication prevails, that is, a giraffe learns about the presence of a danger from the behaviour of its companions.

As a matter of fact, if a giraffe, for whatever reason, starts running, all others will do the same immediately, without even knowing why.

→ For general information about ARTIODACTYLA please click here.