All about carnations. History and hybridisation in Italy.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

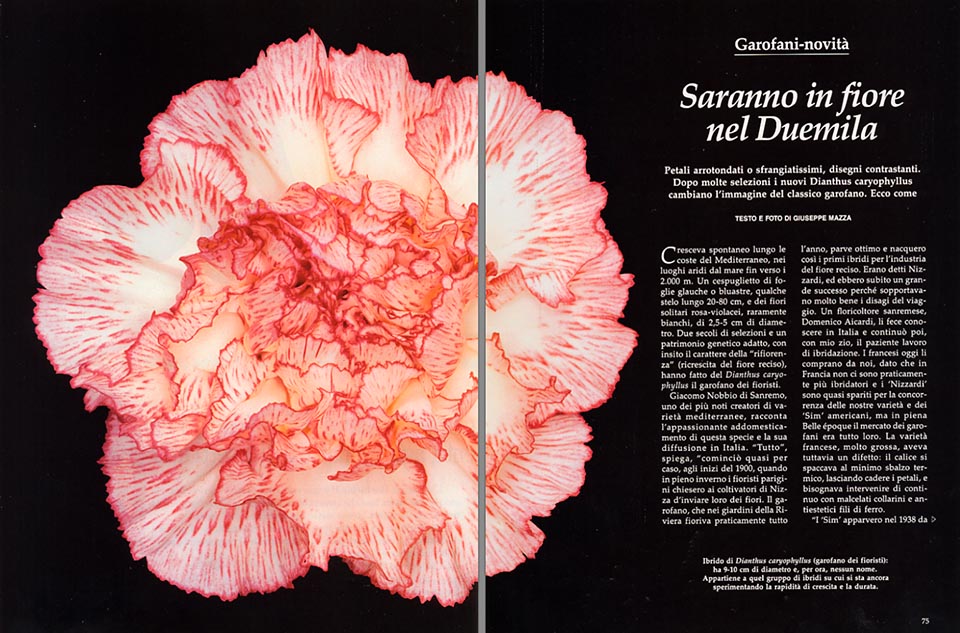

Individualist and stubborn flower, the Carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus).

It steals all the nourishment from the nearby plants, reducing them often to a sorry plight, and, haughty like a king on his throne, seldom offers to its minor buds the chance of developing. Only when the top falls or the stem is cut off, then there is room for a new “tyrant”, which will at once take the place of the first one, in the major interest of the reproduction of the species.

And it’s this peculiarity of the “reflorescence”, the pertinacious new growth after each mutilation of the cut off flower, which has made it so popular in the world of cheap bouquets, especially in winter, when the nature is not prodigal of colours and corollas.

History of a recent domestication, as, in spite of the Greek name of “Flower of the Gods”, coined by Linnaeus with Dios = divine, and Anthos = flower, in the old times the carnations are not mentioned at all. Legends and holy texts ignore them, and authors like Pedanius Dioscorides, Theophrastus, and Pliny, do not consider them worthy of even a single line.

By sure, they were growing here and there on the calcareous crags of the Mediterranean area, and for their spicy scent, between the vanilla and the cinnamon, they were employed, in Middle East and North Africa, in the preparation of a wearisome rosolio, intended for sweets and foods; but we have to wait till 1270, with the return to Tunis of the crusade of Louis IX, sanctified later on, when they start talking about it in Europe.

Due to their properties, vaguely balsamic, tonic of the nervous system, sudoriferous and decongestant, they had relieved the wounded solders, bedridden among the miasmata and the filthiness of the front, and it was believed to be an antidote to plague and cholera.

Nevertheless, it was only in 1442, at Aix en Provence, that their great horticultural adventure did begin.

The hybridizer is no less than René d’Anjou, duke of Lorraine and Bar, and count of Provence, the “Bon Roi René”, as French did call him, renowned defeated man exiled of the war for the Kingdom of Naples, against Alphonse of Aragon. “He found great consolation”, they write, “in cultivating carnations”; and, irony of fate, it’s another illustrious loser, the Gran Condé, Prince Le Héros, put in jail by the Cardinal Mazarin, in the Castle of Vincennes, to resume, two centuries later, the experiments.

So, consolation and hobby in the adverse fate, not to say something worse, because, apart marriages and obsequies, the French nobles were going to the guillotine wearing a white carnation on their chest, symbol of the monarchy, while the revolutionists, led by Napoleon, adorned themselves with a red scarlet carnation, which, later on, became, in perfect antithesis with its botanical nature, the symbol of Socialism.

Even if the Carnations of the florists, all alike, recall the social levelling and of the ideas, typical of the old Communist regimes, it would have been better for Craxi to choose, as symbol, a daisy, perhaps red or pink: a republic of small flowers, where, as it happens for all the asteraceae, the individuality of the corollas vanishes in the common interest, for the construction of a big flower.

But let’s go back to the carnations, which, from the snobbish flowers for few people of the French revolution, become the “flowers of the masons”, as Englishmen were saying with disdain. A scent of want, which, still nowadays, lies heavy on the really splendid creations of our floriculturists.

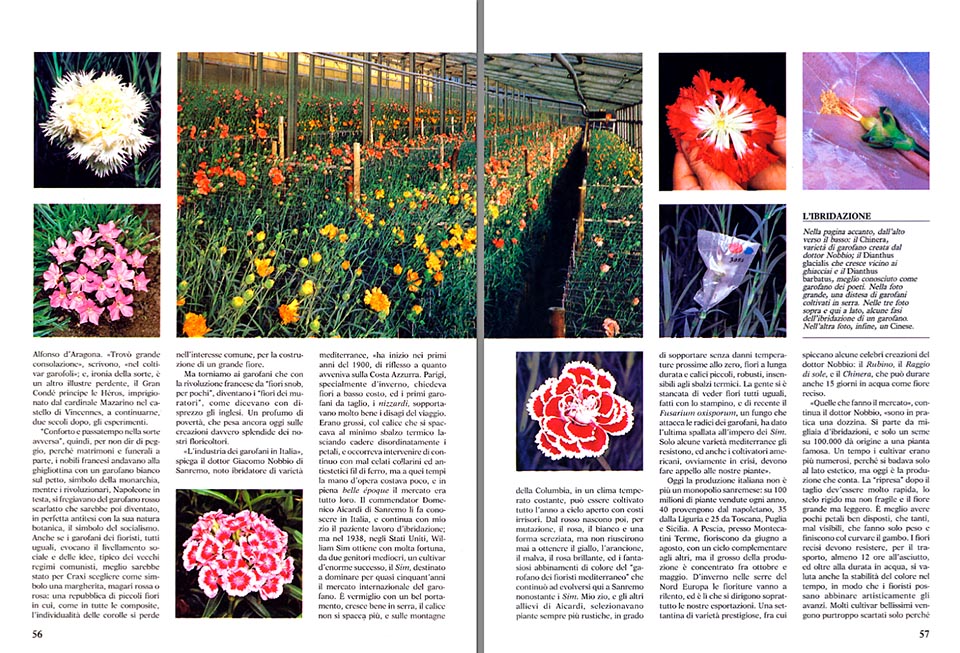

The industry of carnations in Italy, explains to me Dr. Giacomo Nobbio of San Remo, famous hybridizer of Mediterranean varieties, begins during the first years of 1900, as a repercussion of what was happening in the Côte d’Azur. Paris, especially in winter, was asking for low cost flowers, and the first cut carnations, the Niçard ones, tolerated well the inconveniences of the voyage.

They were big, with the calyx which broke at the least thermal variation, leaving the petals to fall down untidily, and it was necessary to intervene continuously with badly hidden small collars and unaestethic wires, but at that time, the cost of labour was low, and in full “belle époque”, the market was all belonging to them. The Commendator Domenico Aicardi, of San Remo, renders them known in Italy, and continues, with my uncle, the patient work of hybridization.

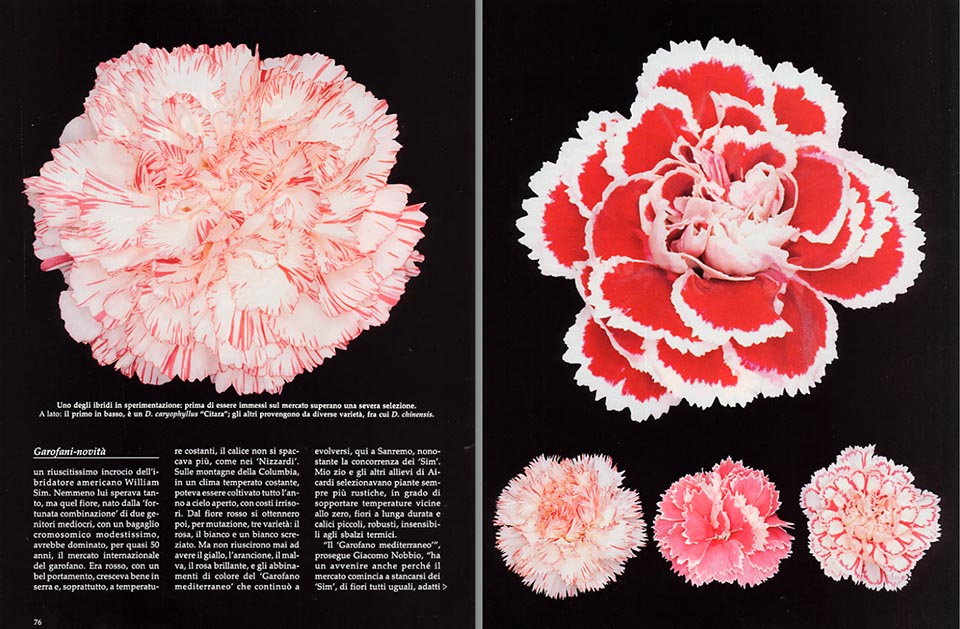

But, in 1938, in USA, William Sim gets, with a lot of luck, from two mediocre parents, a cultivar of enormous success, the Sim, destined to prevail in the international market of the carnation, for almost fifty years. It’s vermilion, with a nice gait, grows well in a greenhouse, the calyx does not break any more, on the mountains of Columbia, in a constant temperate climate, it can be cultivated all the year round, in open air, with insignificant costs.

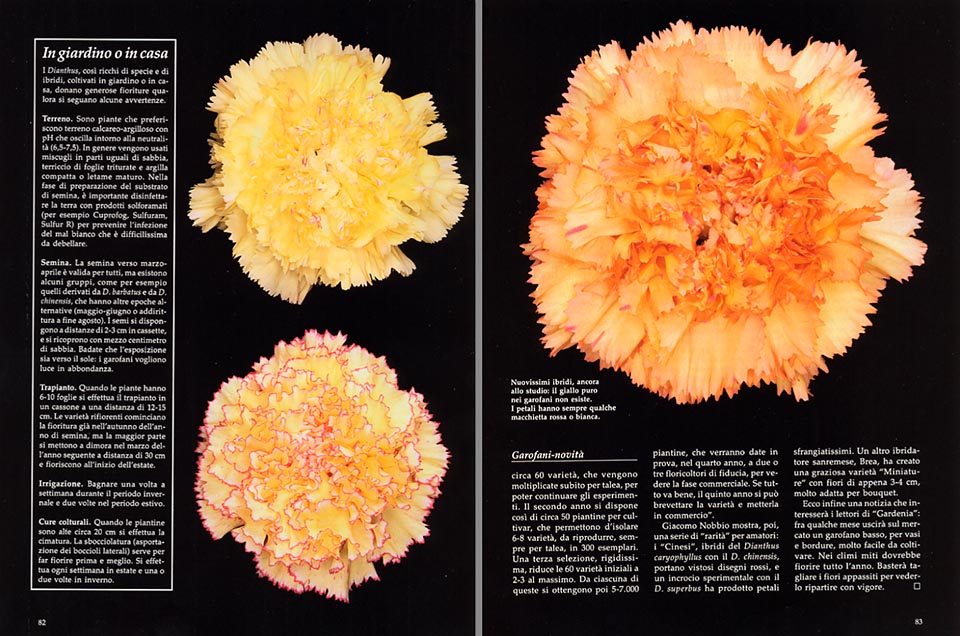

From the red one, issued, later on, through mutation, the pink, the white and a variegated form, but they never succeeded in getting the yellow, the orange, the mauve, the bright pink, and the fanciful matchings of colour of the “Mediterranean florists’ carnation”, which went on in evolving here in San Remo, in spite of the Sim.

My uncle, and the other Aicardi’s pupils, were selecting plants more and more rustic, able to endure, without damages, temperatures close to zero, long lasting flowers and small, strong, indifferent to thermal changes. People is tired to see flowers which are all alike, as done with a stamp, and recently, the Fusarium oxisporum, a fungus which attacks the roots of carnations, has given the final push to the empire of the Sim. Only few Mediterranean varieties resist to it, and also the American growers, obviously in crisis, must appeal to our plants.

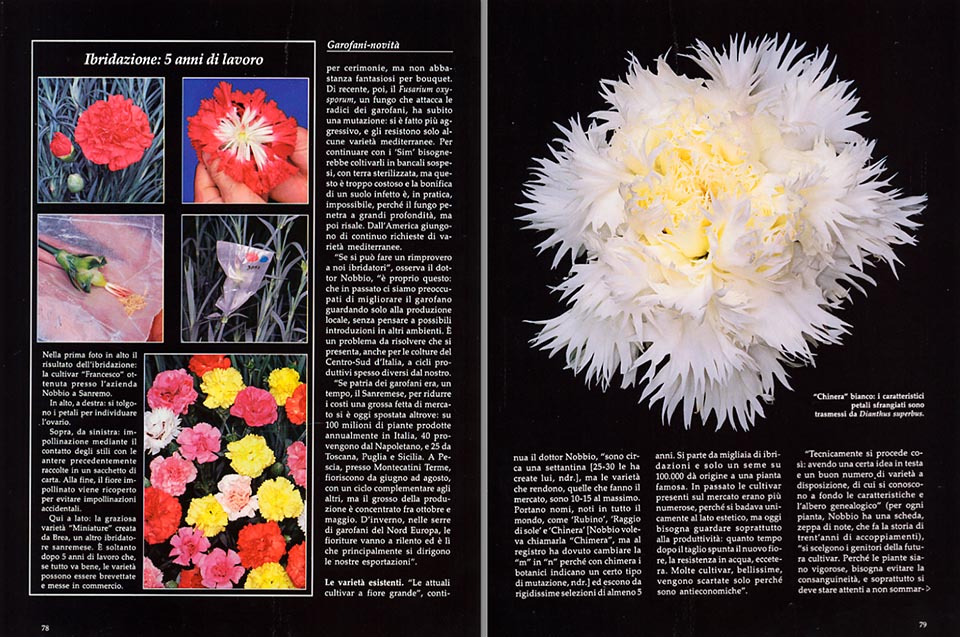

Nowadays, the Italian production is not any more a San Remo monopoly: of 100 million of plants sold each year, 40 come from Naples area, 35 from Liguria, and 25 from Tuscany, Apulia and Sicily. At Pescia, close to Montecatini Terme, they bloom from June to August, with a cycle which is complementary to the others, but the big part of the production is concentrated between October and May. In winter, the flowering in the greenhouses of North Europe go ahead slowly, and it is there that our exports are bound to. About seventy of prestigious varieties, amongst which stand out some Dr. Nobbio’s celebrated creations: the Rubino, the Raggio di Sole, and the Chinera, which can last even 15 days in water as cut flower.

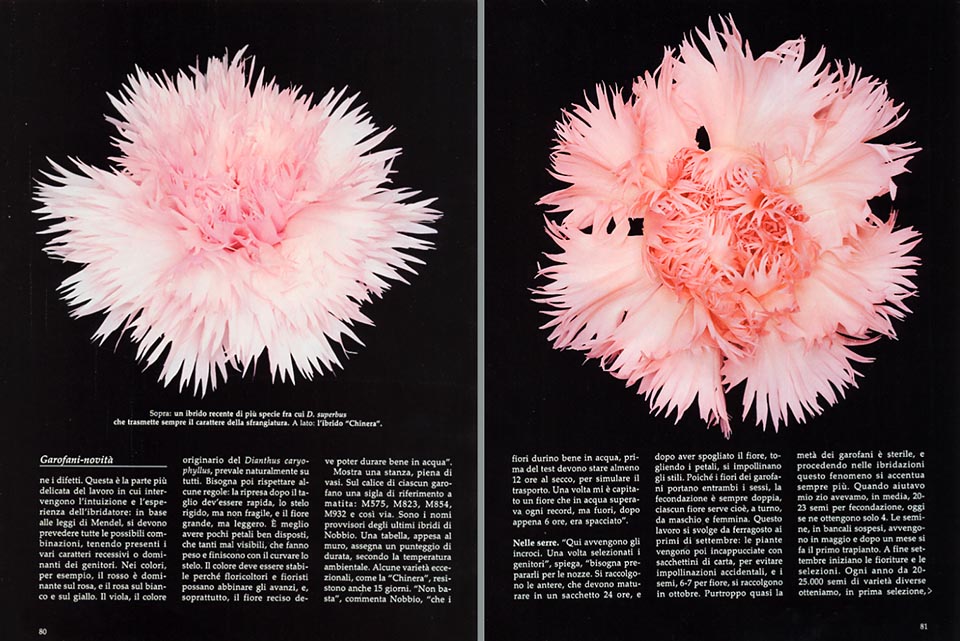

Those which are a good business are practically a dozen. We start from thousands of hybridizations, and only 1 seed over 10.000, gives origin to a famous plant. Once, the cultivars were more numerous, as they were paying attention only to the aestethical side, but, nowadays, it’s the production which is important.

The “recovery” after the cutting must be rapid, the stem hard, but not frail, and the flower, big, but light. It is better to have less petals well disposed, rather than, many of them, but poorly visible, which create only weight and end by bending the stalk. The cut flowers must resist, for the transportation, at least 12 hours in dry conditions, and beyond the duration in water, it is taken in account also the possibility of the colour in time, so that florists can couple the surplus. Many very nice cultivars are unluckily rejected because uneconomical.

He shows me the farm, a very well equipped laboratory for the reproduction in vitro, the tests of duration at different temperatures, and huge expanses of carnations, hooded by small paper sacks bearing a number.

They are used, he explains me, to avoid fortuitous pollinations. In the cross breeds, first of all, it’s important to avoid the consanguinity, and to pay attention in not adding up possible defects. This is the most difficult thing, where luck matches perception and experience.

After Mendel’s law, we must foresee all possible combinations, keeping well in mind the various recessive and dominant characters: among the colours, for instance, the red prevails on the pink, the pink on the white or yellow, and the violet, which is the colour of the untamed form, triumphs, obviously, on all of them.

Once chosen the spouses, they prepare the wedding. The previous day, the collect the anthers, the male organs, which must ripen 24 hours in a small bag, and then, once taken off the petals, they pollinate the styles. An operation which takes place from mid-August to the beginning of September, and in October they already collect the seeds.

Unluckily, almost half of the carnations are barren, and, proceeding with the hybridizations, this phenomenon increases continuously. When I was helping my uncle, we had, on an average, 20-30 seeds for each fecundation, nowadays, we can get only 4 of them. The seeding, on long hanging benches, is effected the following May, and after several transplantations, the flowering and selection begins by the end of September.

Every year, from 20-25 thousand seeds, we isolate about 60 varieties, which are immediately multiplied by grafting in order to be able to go on with the experimentations. These are reduced to 6-8 on the second year, 2-3 on the third, and brought finally to 5-7 thousand small plants to be given, on trial, to the floriculturists on the fourth year, in order to test the commercial phase. Finally, all going well, on the fifth year, the variety can be patented and then placed in the market.

Dr. Nobbio shows me, proudly, a set of carnations for lovers: the “China Pink”, smaller, with showy red drawings, born from the cross breed of the Dianthus caryophyllus with the Dianthus chinensis, and a hybrid with the Dianthus superbus, which has produced very laciniated petals.

Another San Remo producer, Mr. Brea, has created a charming “miniature” variety, with flowers of only 3-4 cm, very suitable for the bouquets of the restaurants, where the corollas must not bother the vision of the guests.

More or less questioned by modern systematics, attentive not only to the flowers, but also to the design of the pollen, the botanical species of carnations are about 300, scattered in Europe, East Africa, South Africa and most of Asia, till Himalayas and Japan. Ant it is mainly on these last ones where are concentrated the interest of the landscape architects, even if today there is a dwarf variety, for edges, of the Dianthus caryophyllus.

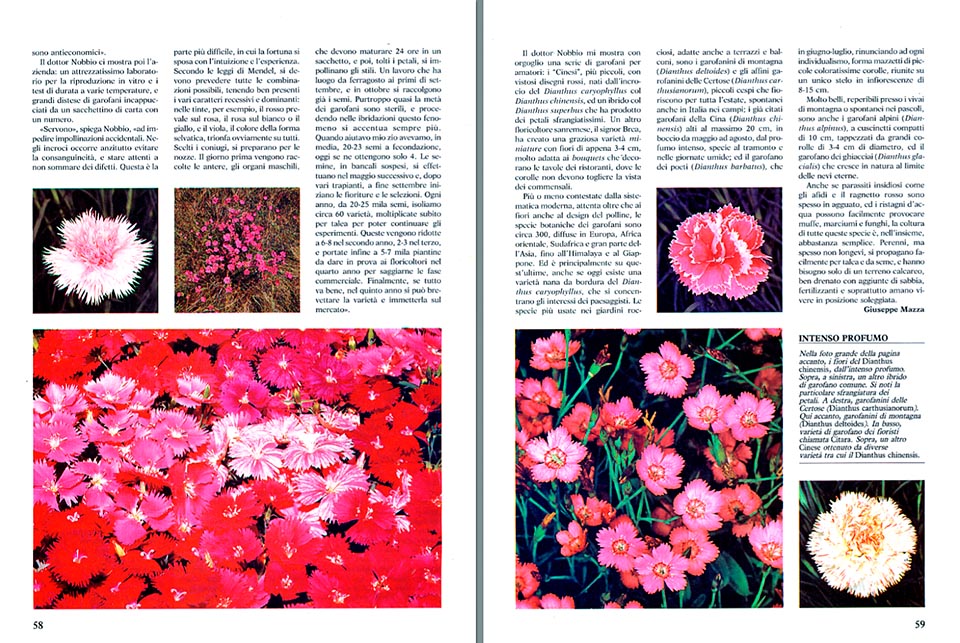

The most used species in the rocky gardens, suitable also for terraces and balconies, are the Maiden Pink (Dianthus deltoides), and the similar Carthusian Pink (Dianthus carthusianorum), small tufts, in flower all the summer long, spontaneous, also in Italy, in the fields; the previously cited China Pink (Dianthus chinensis), tall up to 20 cm, in bud from May to August, with an intense scent, particularly at the sunset and during wet days; and the Sweet William (Dianthus barbatus), which, in June-July, abandoning every individualism, forms small bunches of little corollas, gathered together, on an only stem, in inflorescences of 8-15 cm.

Very handsome, available at the mountain nurseries, are also the Alpine Carnations (Dianthus alpinus), with compact, small cushions of 10 cm, decorated by large corollas of 3-4 cm of diameter, and the Glacier Crowfoot (Dianthus glacialis), which grows up in nature at the limit of the perpetual snow.

Even if insidious parasites, such as the Plant louse and the Red little spider, lie often in ambush, and the stagnant waters can easily generate moulds, rots, and fungi, the cultivation of all these species is, on the whole, quite simple. Perennial, but often not long-lived, they propagate easily by cutting and by seeds and need only a calcareous soil, well drained, with addition of sand, fertilizers, and, chiefly, a lot of sun.

GARDENIA + SCIENZA & VITA NUOVA – 1987

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within the CARYOPHYLLACEAE family please click here.