Unusual Australian flowers rich of sugar which blossom on shrubs and small trees. Cultivation in our climates and reproduction by seed.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

“To put in the oven for 5-10 minutes, or strew with alcohol and light on the fire”. This is not a culinary recipe, but the only way to get certain infructescences of Banksia opening.

Hyper-protective mothers, they release their seeds only when a nice fire cleans well up well, from the weeds, the Australian “bush”, where they live. The darnel, as the Gospel well says, could suffocate the small plants, and, then, the ash, it’s well known, has always been an excellent fertilizer.

So, he who wishes to get seeds from these strange woody “sculptures”, with the fruits artistically placed one over the other, like a totem, often has no choice: one species of two required the “ordeal by fire”. And it’s really an ordeal, with all possible uncertainty, and the risk, every time, to transform the seeds in roasted chestnuts.

The heat must be intense, but short lasting, and, in case of failure, the treatment can always be repeated.

Sometimes, however, the follicles of the “totem”, do not really want to open, and in this case we suggest to plunge the infructescence in the water, and dry it with the hair-dryer. This would be, roughly, the equivalent to a fire followed by an abundant rain and a strong wind capable to carry the winged seeds of the banksias far away from the mother plant.

At the limit of the deserts, where life is difficult, the nature does not want the parents to compete with their offspring and takes care, with hygroscopic mechanisms and other ruses, that the young plants have all the water necessary for their growth.

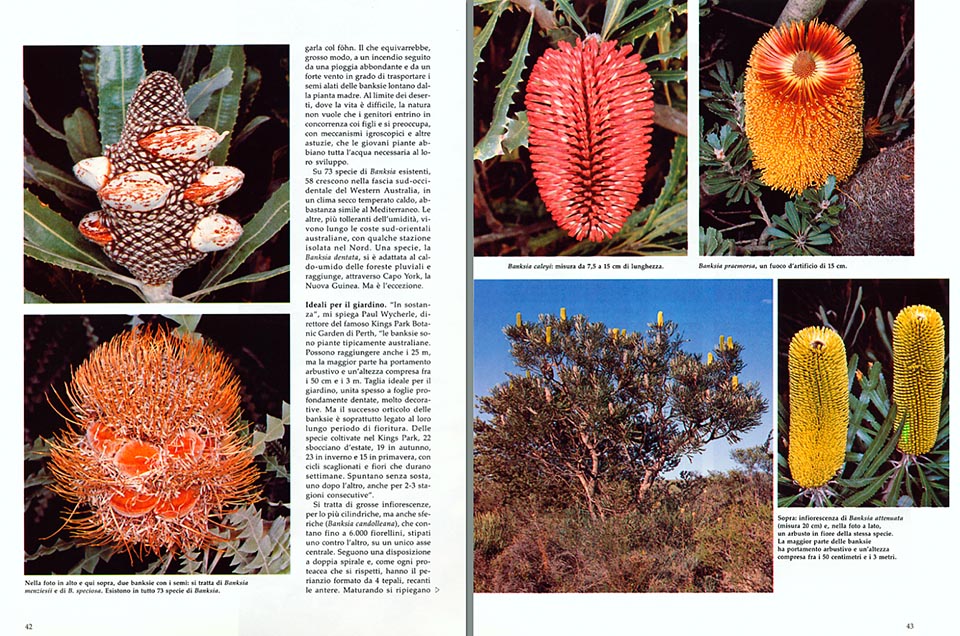

Of the 73 existing species of Banksia, 58 group up in the south western side of Western Australia, in a dry temperate-warm climate, rather similar to the Mediterranean one.

The others, better enduring the humidity, live along the south eastern Australian coasts, with some isolated areas in the north.

A species, the Banksia dentata, has adapted to the humid heath of the rainy forests, and reaches, through Cape York, the New Guinea. But this is the exception.

“Substantially”, explains to me Dr. Paul Wycherley, director of the famous Kings Park Botanic Garden of Perth, “the banksias are plants typically Australian. They can reach even the 25 metres of height, but most of them have a bushy structure and a height between 30 cm and 3 metres. Ideal size for a garden, often united with deeply dentate, very decorative leaves. But the success of the banksias is mainly due to their long flowering period. Of the 47 species cultivated in the Kings Park, 22 bloom in summer, 19 in autumn, 23 in winter and 15 in spring, with variously distributed cycles, and flowers which last even for weeks. They come out incessantly, one after the other, even for 2-3 consecutive seasons”.

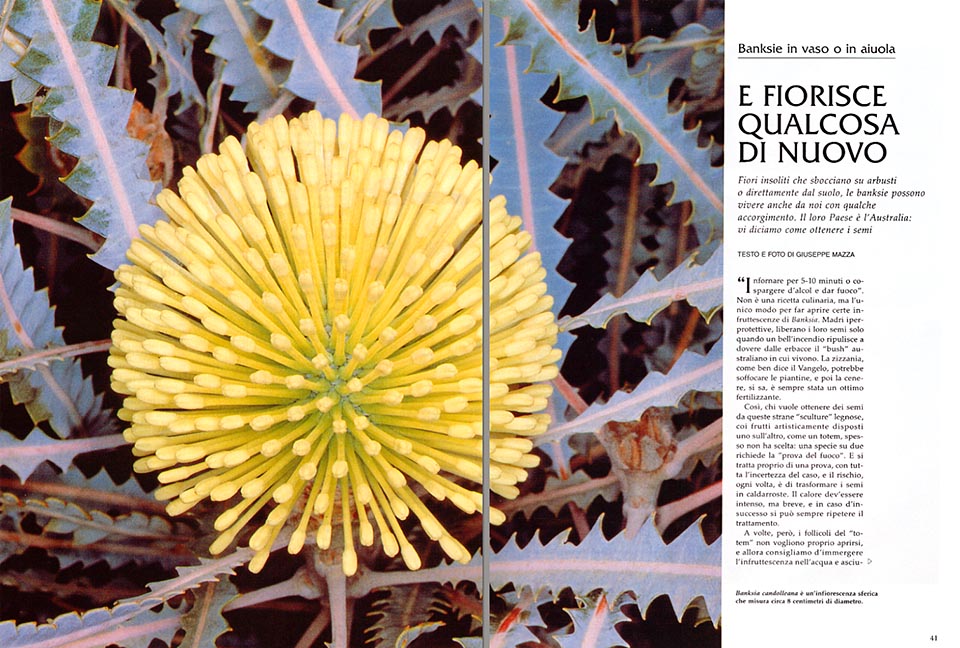

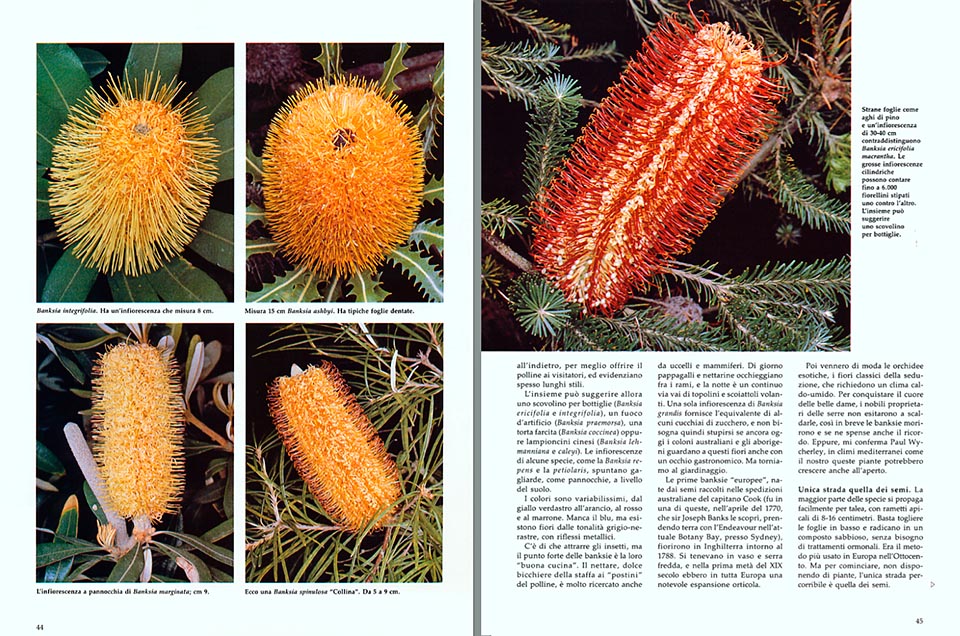

It’s matter of huge inflorescences, mostly cylindrical, but also spherical (Banksia candolleana), which count even 6.000 small flowers, crowded one close to the other, on a single central axis. They follow a double spiral disposition, and like every respectful Proteaceae, they have the perianth formed by four tepals, carrying the anthers.

When they ripen, they turn backwards, in order to offer better the pollen to the visitors, and often emphasize long styles. The whole can then give the idea of a small bottle-cleaner (Banksia ericifolia and B. integrifolia), a fire-work (Banksia praemorsa), a stuffed cake (Banksia coccinea), or some charming small Chinese paper-lanterns (Banksia lehmanniana and caleyi).

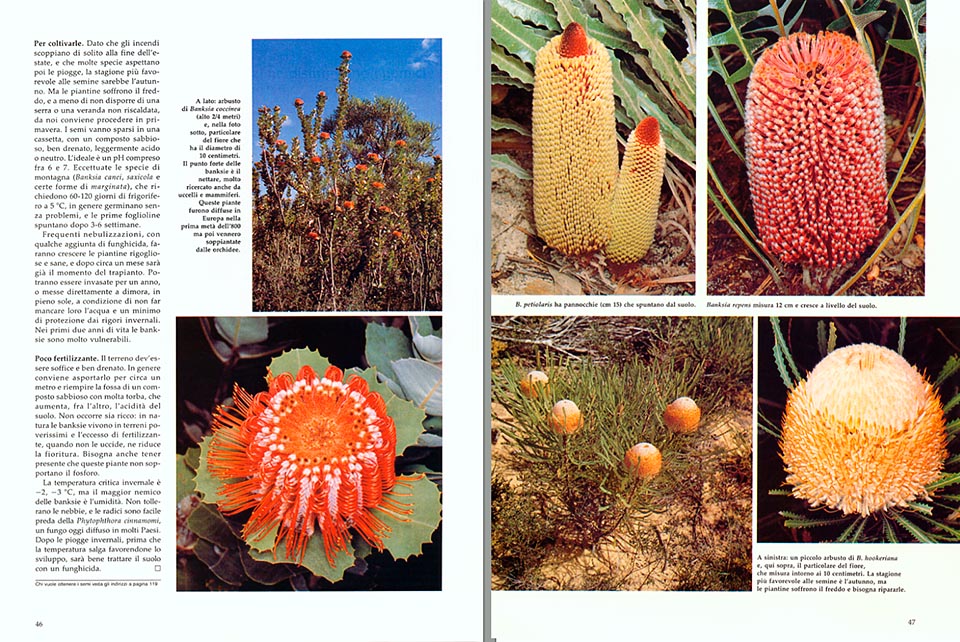

The inflorescences of some species, such as the Banksia repens and the petiolaris, come out, vigorous, like spikes, at the level of the soil.

Colours are very variable: from the greenish yellow to the orange, the red and the brown. The blue is missing, but there are flowers with grey blackish tonalities, with metallic reflexes.

There is enough for attracting insects, but the main point of banksias is the “good cooking”. The nectar, sweet stirrup-cup to the “postmen” of the pollen, is very much sought for also by birds and mammals.

During the day, parrots and nectarinias ogle between the branches, and during the night it’s a continuous bustle of mice and flying squirrels. A single inflorescence of Banksia grandis supplies the equivalent of some spoons of sugar, and we have not to be surprised if, even nowadays, Australian settlers and natives look at these flowers also with a gastronomic eye.

But let us go back to gardening.

The first “European” banksias, born from seeds picked up during the Australian expeditions of Captain Cook (it was in one of these, in April 1770, that Sir Joseph Banks discovered these plants, while landing with the Endeavour in the present Botany Bay, close to Sydney), did bloom in England around the 1788. They were kept in pot and cold greenhouse, and, during the first half of the 19th century, they had a remarkable horticultural expansion in the whole Europe.

Then the exotic orchids, the classical seduction flowers, came into fashion, and they required a warm humid climate.

In order to conquer the hearts of the beautiful dames, the noblemen owners of the greenhouse did not hesitate in warming them up, but in short time the banksias passed away and even their remembrance did disappear.

And yet, Paul Wycherley confirms to me, in Mediterranean climates like ours, these plants might grow up even in open air.

The most of the species, spread easily by cutting, with apical small branches of 8-16 cm. It is sufficient to take off the inferior leaves and place them in a sandy compound, without any hormonal treatment. It is the most used method in Europe in 1800. But for starting, if we do not dispose of plants, the only possible way is the one of the seeds.

Seen that the fires break out normally by the end of summer, and that many species, as we have seen, then wait for the rains, the most favourable season for seeding would be, normally, autumn.

But the small plants suffer from cold, and unless we do not dispose of a greenhouse or of a unheated veranda, in our countries it’s better to proceed in springtime.

The seeds, as always, must be spread in a small case, with a sandy compound, well drained, lightly acid or neutral. The best is a pH included between 6 and 7. Excepting for the mountain species (Banksia canei, saxicola and some forms of marginata), which require 60-120 days of fridge at 5°C, generally they germinate without problems, and the first small leaves come out after 3-6 weeks.

Frequent nebulizations, with some addition of fungicide, will allow the plants to grow up luxuriant and healthy, and after about one month the moment of the grafting will already come.

They will have to be placed in pot for a year, or placed directly in the ground, in full sun, provided they do not miss water and a minimum of protection from the winter inclemencies. The banksias are extremely vulnerable during their first two years of life.

The soil must be soft and well drained. Generally, it is better to take it off for about one metre and fill up the ditch with a sandy compound with much peat, which increases, nevertheless, the acidity of the soil. Its richness is not necessary: in nature the banksias live in very poor grounds and the excess of fertilizer, when does not kill them, reduces their flowering.

We shall have also to keep in mind that these plants, as many proteaceae, do not bear the phosphorus.

The critical winter temperature is -2-3 °C, but the major enemy of the banksias is humidity. They do not tolerate the fogs, and the roots are easy prey of the Phytophtora cinnamomi, a fungus nowadays spread in many countries. After the winter rains, before that the temperature increases favouring the development, it will be wise, therefore, to treat the soil with a fungicide.

GARDENIA – 1990