Experts in the art of seduction, they attract their marriage makers with their pyrotecnical look.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

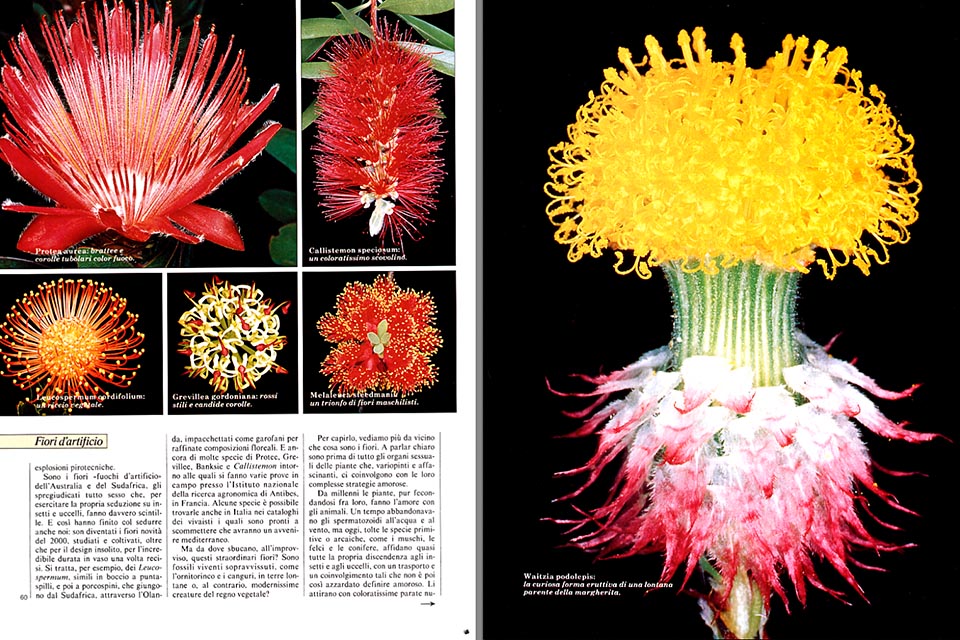

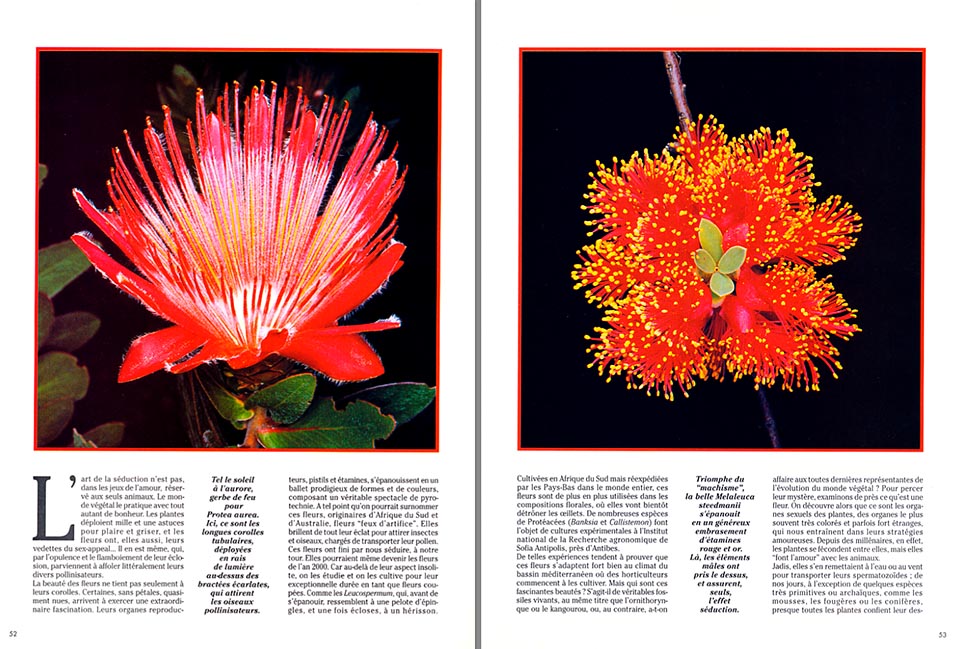

Barren flowers, almost without petals. Open-minded, modern, all sex, with pyrotechnical stamens and pistils. New flowers of the 2000, in fashion, apart the unusual design, for the incredible duration in vase, once cut off.

The Leucospermum, similar, when in bud, to pincushions, and then to porcupines, come already to us from South Africa, via Holland, wrapped up like carnations for refined floral compositions; and at the National Institute of Agronomical Research of Antibes, France, they test on various fields in open air, many species of Protea, Grevillea, Banksia, and Callistemon.

It is possible to find them, also in Italy, in the catalogues of the nurserymen, and, by sure, they will have a Mediterranean future.

But, where are they coming from, suddenly, these never seen flowers?

Are they “living fossils”, survivors, like the duckbill and kangaroos in far away countries, or, on the contrary, very modern flowers?

In order to understand it, let us see, at close quarters, what the flowers are.

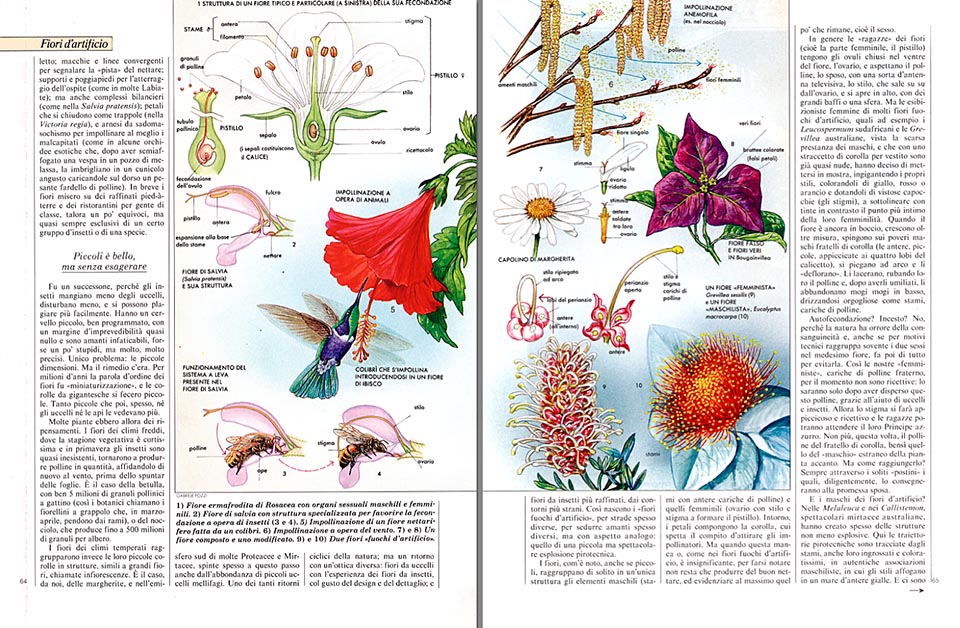

Even if, often, they are taken as symbol of virginity and purity, to talk clearly, they are the sexual organs of the plants. Revelation by itself rather shocking, which makes us to see suddenly a nice bunch of flowers as a bundle of sexual organs of a bull or vulvae of a female cat; but, willing or not, the many-coloured sexes of the Green World fascinate us, and their complex amatory strategies do involve us.

Since millennia, in fact, the plants, even if coupling between them, are making love to the animals.

Once, they ware abandoning the spermatozoa in the water and the wind, but now, excluding the archaic or primitive species, such as mosses, ferns, and conifers, they entrust almost all their offspring to the insects and the birds, with such a transport and involvement, that it is not hazardous to define same as amorous.

They attract them with very coloured nuptial parades; they seduce them with beauty and scent; offer them a shelter for the night and the bad weather; and then, like in the best ménage, they exploit them , transforming them in, more or less aware, “postmen”, to carry their pollen to destination.

The “post office”, the meeting point, is the flower: a clever invention, with which, about 100 millions of years ago, in the rainy forests, the plants have, under a certain point of view, animalized.

To conquer somebody, it is a good tactics to show immediately the same tastes, the same opinions; and to seduce the birds, which notoriously, love colours, during the Cretaceous, the plants invented a many-coloured structure, the flower, completely extraneous to their Green World.

As it happened long time ago, with the birth of the first animals, generated by a plant which had lost the capacity to effect the photosynthesis, so, also the second animalization of the plants happens with a “loss”.

Some leaves, that is, renounce to the chlorophyll, and get coloured, becoming petals. A metamorphosis which we can see, still now, in force, in “undecided” species, such as the Bougainvillea, the Christmas Star, or the Bromeliads, with the leaves lacquered of red, which turn, down below, into green.

Flowers or leaves? Who cares. We like them, and also the birds did so, 100 millions of years ago.

Garish colours, crested forms which imitate the plumage, pressing invitations to Pantagruelian hearty meals of nectars with small salads of petals: the flowers were doing everything to seduce them, and the birds gobbled happily.

They had, it is true, the grace of an elephant in a shop of china ware, but the pollen was reaching, with precision, the destination, even in the thickest forests, where, by sure, the wind was not like one of the family.

With some ruses to protect their genital organs, and the offspring, from the voracity of these cumbersome partners, the flower plants were prosperous, and increased so much in number, that, quite soon, the forest began to be too tight for them.

The most enterprising species then moved to the conquest of the temperate areas; but where in winter the vegetative life makes a pause, where there is not plenty of fruits all the year round, the birds are short.

For a moment, the flowers look around, puzzled, and then, seen that the insects were buzzing in the sky, with a smart reconversion, adapted their petals to the tastes and the colours of the new customers.

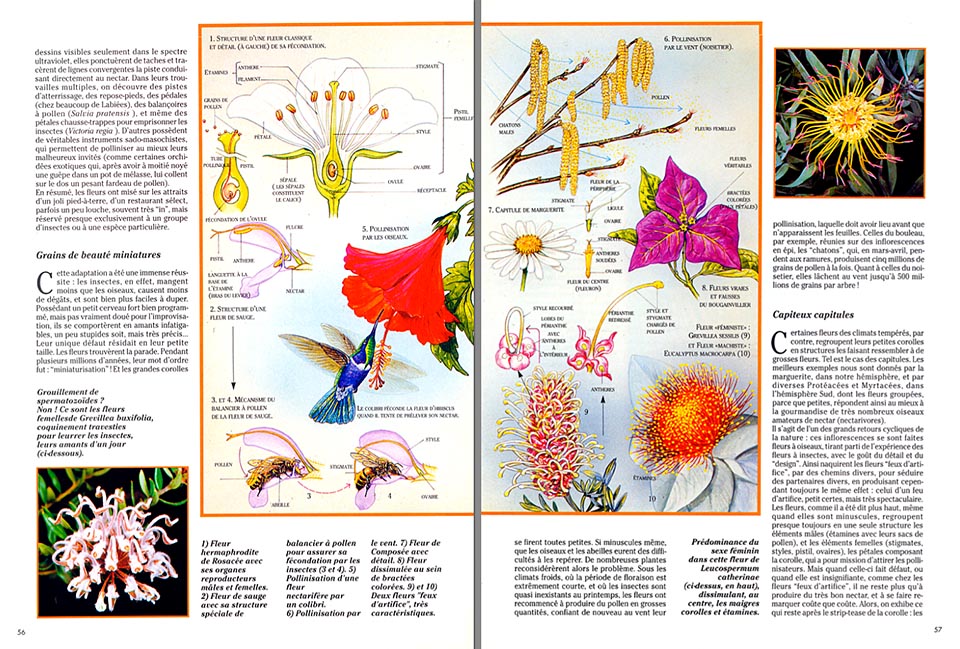

The white, the blue, and the yellow, with reflexes and drawings visible at the ultra violet; dots and lines converging to mark out the way of the nectar; supports and footrests done specially for the landing of the guest; but also complicated balance-wheels, petals which close like traps, sadomasochism implements, to pollinate, in the best possible way, the victims.

In brief time, they set up refined “small restaurants”, for stylish people, at times somewhat ambiguous, but almost always exclusive of a certain group of insects or of a species.

It was a big success, because the insects eat less, cause less mess than the birds, and can be plagiarized more easily. A small brain, well programmed, with a margin of unforeseeable initiative almost null; untiring lovers, maybe a little stupid, but perfect, very very accurate.

For millions of years, the password of the flowers was “minimization”, and the corollas, from gigantic, became smaller and smaller. So much small, that then, often, neither birds nor bees could see them any more.

Many plants, then, did change of mind. The flowers of cold climates, where the vegetative season is very short, and in spring insects are almost not existing, resumed producing pollen in quantity, entrusting it again to the wind, before the sprout of leaves.

It is the case of birch, with even 5 millions of granules per catkin (in this way, botanists call the “small tails” of flowers which in March-April are hanging from the branches), or the hazel, with 500 millions of granules per tree, a “joy” for those who suffer from allergies.

And those of temperate climates, seen that once a certain evolution choice has been done, it is not easy to go back, gathered their small corollas in structures, similar to large flowers, which botanists called inflorescences.

It is the case, in our countries, of the daisies, and, in the southern hemisphere, of many Proteaceae and Myrtaceae, which were often pushed to this step also by the abundance of small honey eating birds. One of the many cyclical returns of nature; but a return with a different point of view, like what you get up in a mountain road, when you reach a higher hairpin bend.

Bird-flowers with the experience of insect-flowers, with the taste of details; and insect-flowers more refined, with the most strange outlines.

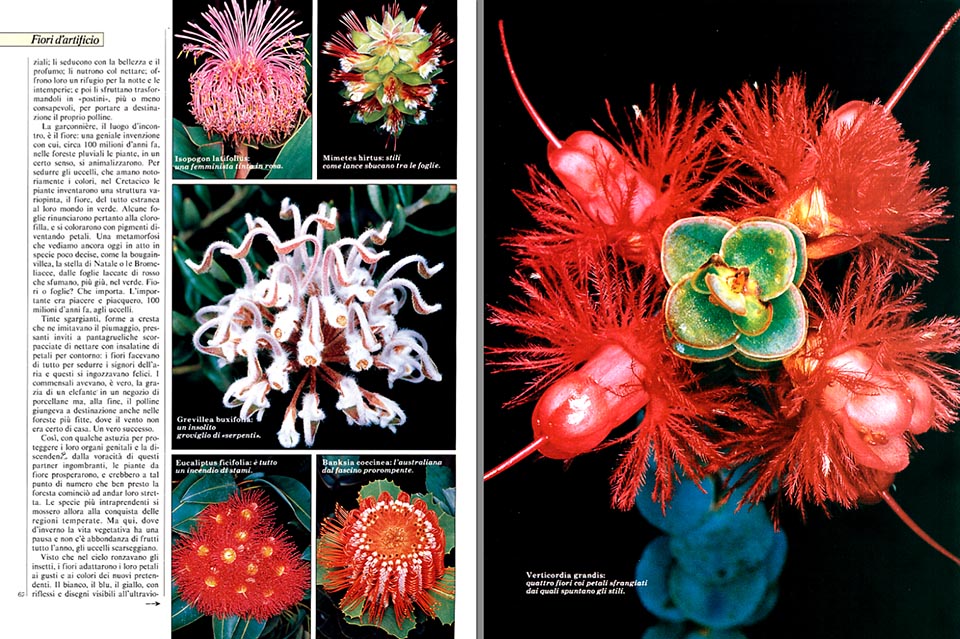

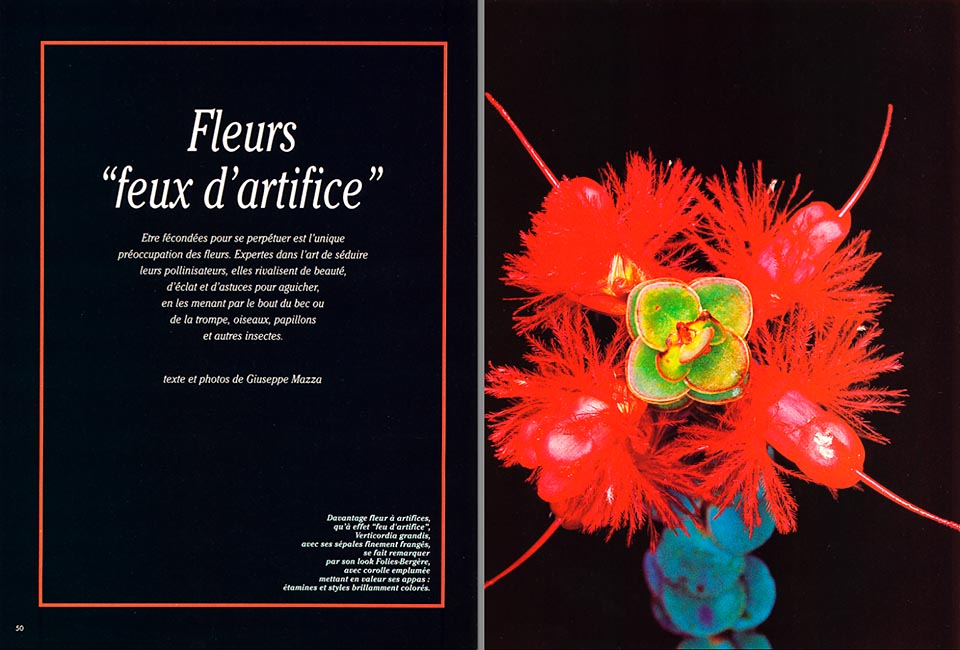

In this way, come to birth the “fireworks flowers”, through often different ways, to seduce often different lovers, but with similar appearance, the one of a small pyrotechnical explosion.

As it is well known, the flowers, even if small, usually group in one sole structure the masculine elements (stamens with anthers loaded of pollen), and the feminine ones (ovary with stigma and style).

Around, the petals, free or united, form the corolla, the advertising apparatus which has the duty to attract pollinators.

But when this is not present, or, like in our case, is negligible, in order to call attention, there is no other solution than to produce some good nectar, and exhibit at the maximum, enlarging it, the little which remains, that is, the sex.

The “girls” of the flowers, are, usually, traditionalist, and discreet: they keep the ovules closed at home, in the belly of the flower, and wait for the pollen, the bridegroom, with a sort of “TV antenna”, the style, which rises from the ovary, and opens on the top, on the “roof”, with large whiskers or a sphere.

But the females of the Leucospermum, in South Africa, and of the Grevillea, in Australia, seen the inefficiency of the males, and that, with a small rag of corolla as dress, already almost naked, decided to show off.

“Enough with the shames”, they told themselves, “enough with hiding, enough with waiting”, and so have magnified their styles, colouring them of yellow, red or orange, with showy heads, the stigmas, which point out with often strong, contrasting colours, the most intimate point of their femininity.

When the flower is still in bud, they grow up beyond measure; push on the miser males, small, stuck on the four lobes of the small calyx,they bend as an arc, and deflower them. They lacerate them, stealing their pollen, and, after having humiliated them, they abandon them below, downhearted, standing up, proudly like stamens, loaded of pollen.

Self fecundation? Incest? No, because our “feminists”, loaded of brotherly pollens, for the moment, are not receptive: they take the “pill”, and only after having dispersed the pollen, flouring duly, birds and insects, resume dreaming, and awaiting, alike all the girls of the world of flowers, their Charming Prince.

The stigma then becomes sticky, receptive, and the pollen coming from other inflorescences, reaches the ovary with a different genetic patrimony. Nature hates consanguinity, and even if, for technical reasons, it often groups the two sexes in the same flower, does its best to avoid it.

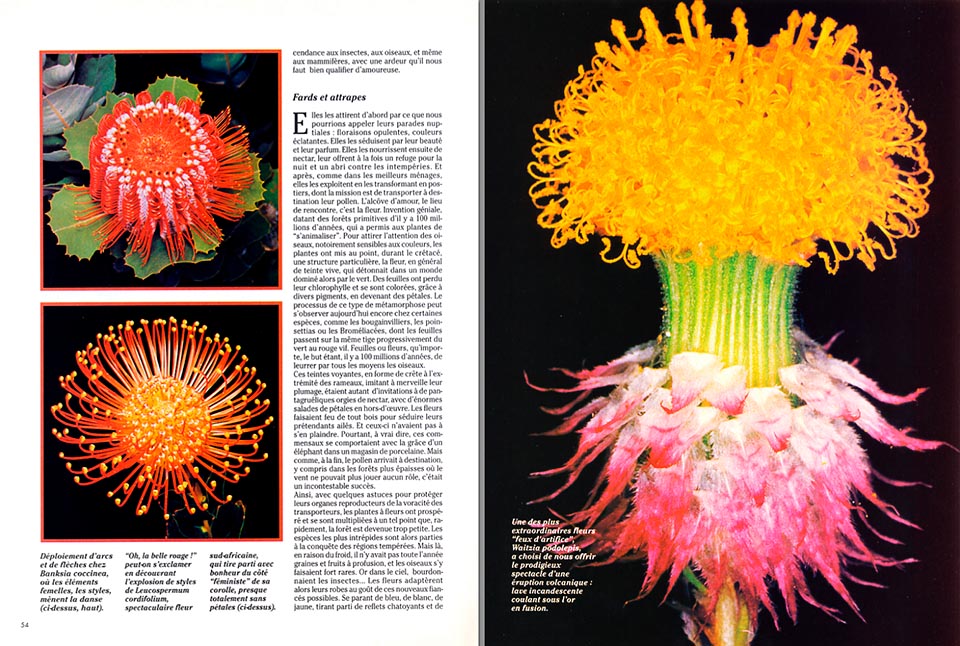

And the males of the small flowers? By sure, they have not remained always idling. In the Melaleuca and the Callistemon, Australian Myrtaceae, have often created structures which are not less explosive.

Here the pyrotechnical trajectories are drawn by the stamens, them too, magnified and very coloured, in genuine sexist associations, where the styles drown in a sea of yellow anthers.

And not even the “soloists” are missing, large, single, flowers, wide even 8 cm., such as the Eucalyptus macrocarpa, the “Mottlecah”. They should have the right to be proud, for having obtained, with just one flower, the effect of hundreds of feminists, but the males of the eucalypts are not satisfied, and, they too, often, place themselves close to each other with spectacular inflorescences. Clouds of red or yellow stamens, a real sexist triumph, as is the case of the mimosas, which, absolutely unaware of representing, in Italy, the women movement, are, in reality, typical phallic flowers.

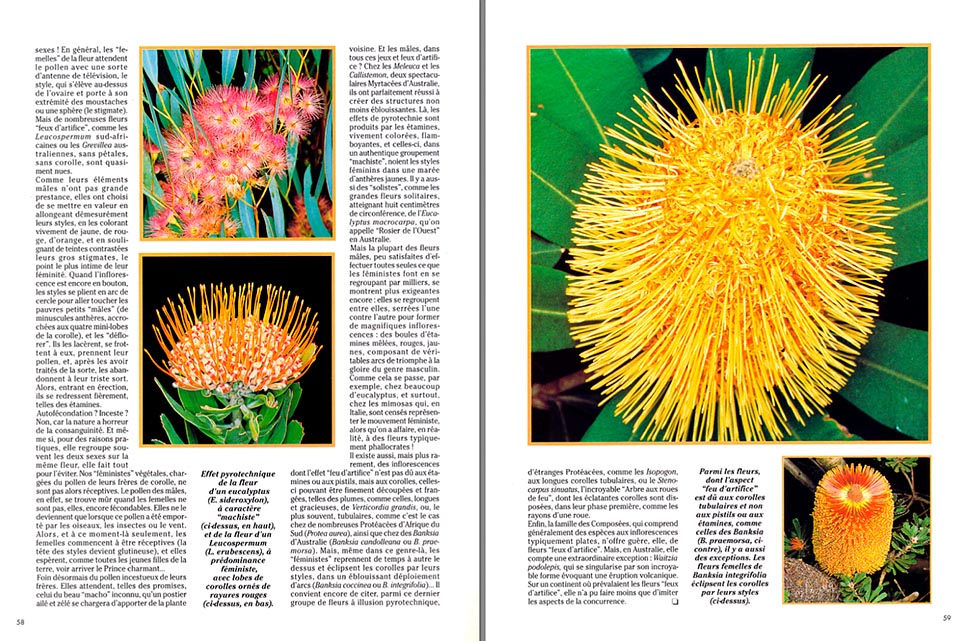

There are also, but not often, inflorescences where the effect pyrotechnical is entrusted to long and thin corollas.

This is the case, in South Africa, of proteas such as the Protea aurea, and, in Australia, many Banksias, such as the Banksia candolleana or the Banksia praemorsa, when like for the Banksia coccinea or the Banksia integrifolia, the feminists show up again, with their styles and the “dance of the bows”. This is the case of odd Proteaceae, like the Isopogon or the Stenocarpus sinuatus, the incredible “Queensland firewheel tree”, with the showy scarlet corollas placed, when young, like the rays of a wheel.

The asteraceae, usually flat, do not offer us many fireworks, but, always in Australia, the Waitzia podolepis, astonishes for the incredible eruptive form. In order to seduce the insects in a country of pyrotechnical explosions, it could not avoid the design of the competitors.

CULTIVATION

BANKSIAS:

Of 73 species of existing Banksias, 58 grow up in the south western side of Western Australia, in dry temperate-warm climate, quite similar to the Mediterranean, and others, which bear better the humidity, along the south eastern coasts of Victoria.

Depending on the species, they flower in all seasons, and some of them are budding incessantly for 6-9 months per year.

In our country, in the Riviera, Paul Wycherley, director of the famous Kings Park Botanic Garden of Perth, confirms to me, they could grow up also in open air.

Most of them propagate by cutting, with small apical branches, of 8-16 cm. It is sufficient to take off the leaves below, and they easily root in a sandy compound, without any need of hormonal treatments. But to start, if we do not find “mother plants”, the only possible way is the one of the seeds.

In Australia, Banksias are sown in Autumn. But in our countries, seen that the small plants do not stand the cold, and unless we dispose of a greenhouse or a not heated veranda, we have to proceed in spring.

The seeds must be scattered in a small case, with a sandy compound, well drained, slightly acid or neutral. Best thing is a pH between 6 and 7. All mountain species (Banksia canei, Banksia saxicola and some forms of Banksia marginata), the seeds of which require a “preventive treatment” of 60-120 days in the fridge, at 5°C, generally germinate without problems, and the first small leaves come out after 3-6 weeks.

Frequent nebulizations, with some addition of fungicide, will let the small plants to grow up luxuriant and healthy, and after about one month, they must be transplanted. They can be cultivated in a pot for one year, or even, placed in the ground, in bright sunshine, on condition to water them and to grant them some protection against winter rigours. In fact, during their first two years of life, the Banksias are extremely vulnerable.

The ground must be soft and well drained. Normally, it is better to take it off for about one metre, and fill up the hole with a sandy compound with a lot of peat, which increases, among other things, the acidity of the soil. It is not necessary this to be rich: in the wild the Banksias live in very poor grounds, and, besides not tolerating the phosphorus, the excess of fertilizers kills them, or drastically reduces their flowering.

They bear, without damages, winter temperatures of -2°, -3°C, but succumb easily to the fogs.

GREVILLAEAE:

Besides the botanical forms (about 250 species), the Australian nurserymen offer several resistant hybrids, often born by chance, such as the Poorinda of Victoria, in the gardens of lovers.

The Grevillea robusta has naturalized in some Mediterranean places; and the Grevillea rosmarinifolia, very rustic, gladdens, since years, the parks of the Riviera.

Each species has its particular requirements. Generally, we can say that these plants need sandy soils, well drained, slightly acid, and poor in phosphorus.

But some of them, on the contrary, love clayey soils.

The winged seeds, one or two per fruit, usually require, for germinating, some minutes of soaking in warm water, and are to be spread, in autumn or spring, on a sandy and friable compound, watered or nebulized several times per day.

The best period for cuttings is the end of summer. The roots, supported by a hormonal treatment, grow up abundant at once, and in order not to break them when the moment of transplant has come, each small branch must have its own pot.

Apart few species in mid-shade, the Grevilleas love the bright sunshine and well ventilated places. The humidity, more than the cold, is often the impediment to the diffusion of these plants in our climates, but at the Botanic Orchard of Canberra, they are grafting, successfully, the most difficult species on feet of Grevillea robusta.

PROTEACEAE AND LEUCOSPERMUM:

Between 1780 and 1820, Prof. John Patrick Rourke, eminent taxonomist of the botanical orchard of Kirstenbosch, South Africa, explains to me, many South African proteaceae were cultivated in Europe.

They were introduced, with success, by the famous Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew, in France, Germany, Italy, and even in Russia. In San Sebastiano, close to Turin, for instance, the marquis of Spigno, had a very rich collection. Then with the arrival of the orchids, and of other exotic plants, the greenhouses, which before were not heated, became warm and humid, and the South African Proteaceae, which need dry air and a long period of rest in winter, with low temperatures, died all, and quickly.

In places like Elba Island, or Sardinia, where the soil is acid and the climate favourable, they can easily be cultivated in open air. Otherwise, we must shelter them, or prepare some “poaches” of acid ground, close to the roots, with peat and sand of quartz. There are hundreds of species available.

They easily reproduce by cutting or by seed, but they need, in any case, winter temperatures of 10°C, abundant watering around the end of winter, and soils rather poor in phosphatus and potassium, with a pH between 4 and 6.

FLOWER EUCALYPTS:

Flower eucalypts, easy to cultivate in a Mediterranean climate, can be already found in the nurseries. But for the most unusual species (there are about 600 of them), we have often to write to Australia.

All are to be sown by the beginning of spring, in small cases full of a sandy and light compound, covered by a glass and some old newspaper.

They must stay at a temperature of 13°-15°C, and only when something begins to come out, after about 2 weeks (for some species even 2 months), the protections can be removed. The case, well exposed to the light, but not to the direct sun, is to be watered by capillarity, with partial immersions in larger basins. After about twenty days, when the small plants show two large leaves and the following ones are growing up, a quick transplant in small pots, is necessary, with allowing the roots to dry up.

The baby-eucalypts are then to be gradually transported to the sun, and carefully watered during the whole summer. In autumn, when they overcome the 15 cm., they can be finally placed in the ground, without uprooting them, with all their “bread of earth”.

Even if some species tolerate the calcareous soils, the ground must be rather neutral or acid. Fertility is not important: it is sufficient that it is exposed, drained, and humid in summer, at least till the plant is not enough big to look for water by itself, with its deep roots.

As a rule, the eucalypts grow up fast (even 5 metres in 3 years), and you will discover that the shape of the leaves and their point of junction on the branches, change surprisingly with the time. The experts mark four stages (germinative, juvenile, intermediate and adult), with four different types of leaves and only when the plant will be adult, with its final foliage, you will see the first flowers coming out.

CALLISTEMON:

Called also Bottle brushes, they are shrubs and saplings endemic to Australia and Tasmania.

They can be easily found in nurseries, and grow up well in open air in the marine places of central-southern Italy.

They accept all grounds, provided they are well drained, and well exposed. They must be scarcely watered in winter, and propagate easily in June with partially woody cuttings.

The “way of the seed” is longer. They must be sown in March, on a warm bed, utilizing a light compound. Then they must be transplanted in small pots of 7-8 cm. They must spend the winter at a temperature around 7°C, and, the following March, must be changed of pot, and another year is necessary for their installation in the final place.

Analogous, but often more difficult, is the cultivation of the Melaleuca.

WAITZIA PODOLEPIS:

It is not easy to find it in Italy, but the seeds can be asked to the Australian nurserymen. It should grow up easily in a Mediterranean climate.

NATURA OGGI + TERRE SAUVAGE – 1989