Unusual bulbous, mostly of South African origin, easy to cultivate in Mediterranean climates.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Classifying plants means simply going through their history, and narrate the adventure of their evolution.

And as the flowers, which are the sexual organs of the Green World, develop more slowly than the stems, leaves or roots, botanists, above all, consider their structure in order to group them.

In this way were born the concepts of gender, species and family, those Latin names often difficult to assimilate, which are used by the students and the passionate people of all the world for understanding each other, and by the taxonomists to set things in order.

In connexion with this, the great Linnaeus had gotten for the first the idea to count the stamens, and to group the plants after their disposition and number; but it was only an inexact approach, just like pretending to classify persons by the size and length of their nose.

Nowadays, even if keeping this as a base, they consider also other elements, like the architecture of the corollas, their position inside the inflorescences, the chromosomes, or the “design” of the pollens, which are typical of every species.

It can happen, therefore, with the despair of the nursery keepers, usually very much conservative, that Latin names do change, and that a plant, or a group of plants, slide, following the opinions, from a family to another one.

It’s the case of the Amaryllidaceae, a much discussed group with hundreds of species, more or less wide depending if the definition of “lilies with lower ovary” is strictly followed, or if exceptions to this principle are accepted, taking in consideration also other elements, such as the umbrella structure of the inflorescences.

So, for somebody, the Allium and the Agapanthus would be by now démodé in the Liliaceae, and the agaves, once undoubtedly Amaryllidaceae, would have now their own family: the Agavaceae.

Here, after having established that philo-genetically the Amaryllidaceae evolve from the Liliaceae, with some characteristics of the Iridaceae, rather than settle the matter, we shall confine ourselves, leaving aside the well known narcissus, snowdrops and amaryllis, to talk about the uncommon species, mainly South African, which appear as “alternative flowers”, and “for amateurs”, in the gardening world.

It is matter always of bulbous plants, or kindred: plants for “difficult habitats”, which overcome the long drought periods with underground structures, made for storing water and food, for short, but intense, vegetative exploits; plants which often disappear for months, losing the leaves, but which are satisfied with a handful of sand in a pot, and recompense for the patient waiting times, with showy flowers.

Depending on the rainy season in their original countries, they can be split in three groups: species with winter growth, which wake up in our countries in October-November; species with a summer growth, moving in March-April, and evergreen species, like the bush lilies, with strong and fleshy leaves, which last long time.

The difficult thing, in cultivation, stays in knowing to which category they belong; but if missing specific information about when watering them, the general rule stands to “leave the plants to decide”.

If, even if watered, the leaves fade, it means that the moment has come to reduce and then to stop watering; and if, without being watered, they come out again, that means that they need water again.

Let us see concretely the different species.

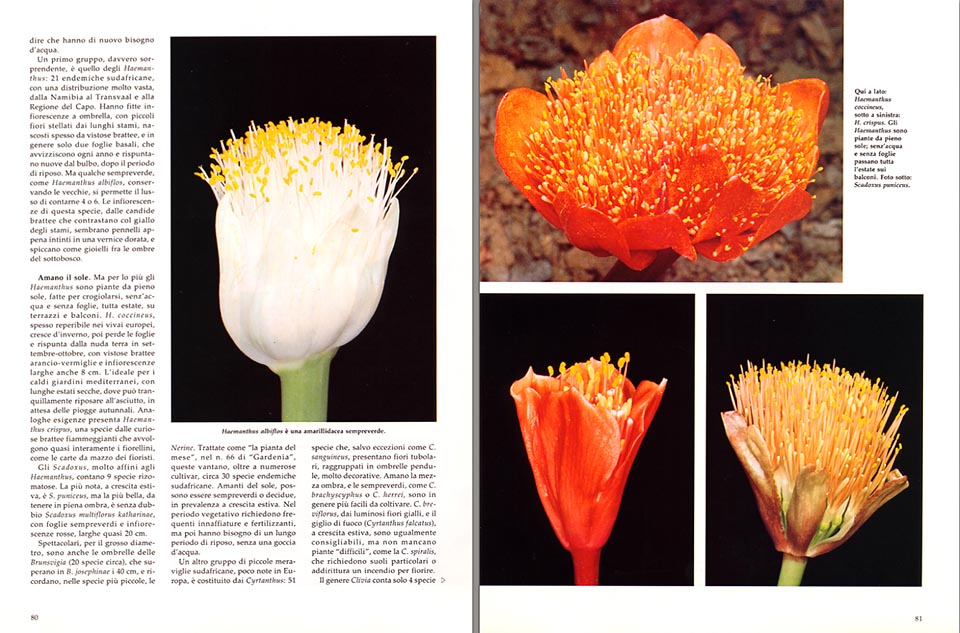

A first group, surprising indeed, is that of the Haemanthus : 21 South African endemics, with a very ample distribution, from Namibia to Transvaal and the Cape region.

They have thick umbrella inflorescences, with small starry flowers with long stamens, often hidden by showy bracts, and usually only two basal leaves, which fade every year and spring up again, new, from the bulb, after the period of rest.

But some evergreens, such as the Haemanthus albiflos, keeping the old ones, takes the liberty to have 4 or 6 of them.

The inflorescences of this species, with the candid bracts which contrast with the yellow colour of stamens, look like brushes just dipped in a golden paint, and stand out, like jewels, among the shade of the under wood.

But, mostly, the Haemanthus are plants of broad sunlight, done for basking, without water and without leaves, for the whole summer, in terraces and balconies.

The coccineus, often easily found in the European nurseries, grows up in winter, then loses the leaves and sprouts from the bare ground in September-October, with showy orange-ruby bracts and inflorescences even 8 cm wide.

Ideal for the warm Mediterranean gardens, with long dry summers, where it can tranquilly rest out of any rain, waiting for the autumnal precipitations.

Similar requirements has the Haemanthus crispus, a species with uncommon flaming bracts, which surround, almost completely, the little flowers, like the papers used by florists to wrap the bunches of flowers.

The Scadoxus, very similar to the Haemanthus, have 9 rhizomatous species.

The best known, growing in summer, is the puniceus, but the most beautiful, to be kept in full shade, is, without any doubt, the Scadoxus multiflorus katharinae, with evergreen leaves and red inflorescences, wide almost 20 cm.

Spectacular, due to their large diameter, are also the umbrellas of the Brunsvigia (about 20 species), which overcome the 40 cm. in the case of the josephinae, and recall, in the smaller species, the Nerine.

These have various cultivars and about 30 endemic South African species.

Fond of the sun, they can be evergreen or deciduous, mainly with summer growth.

During the vegetative period, they require frequent watering and fertilizers, but then they need a long resting time, without any drop of water.

The most rustic species are the bowdenii, used to the frost, and the angustifolia, which tolerates only short-lasting icy weather.

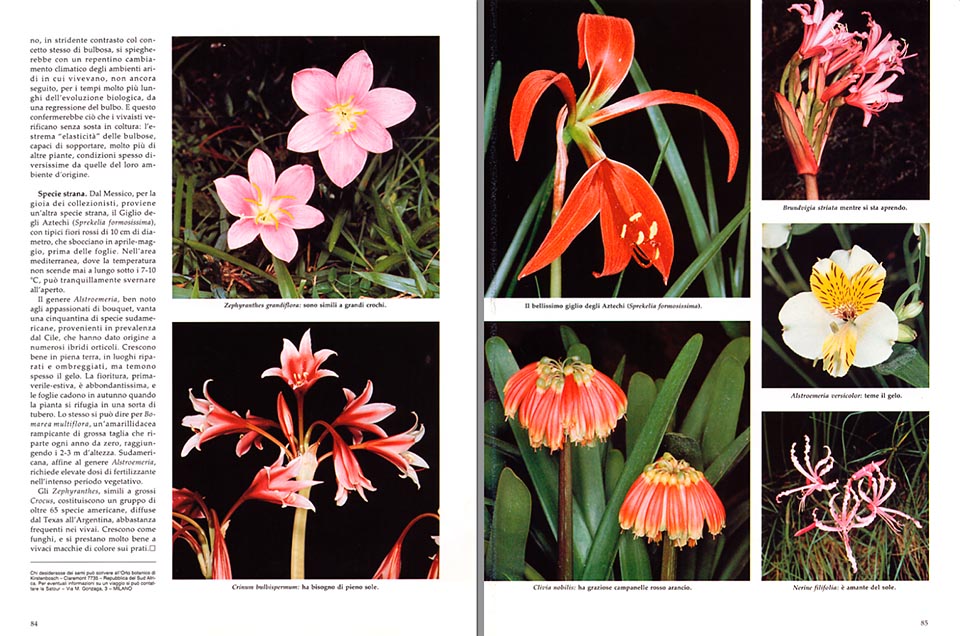

Another group of small South African wonders, little known in Europe, is formed by the Cyrtanthus : 51 species, which, but exceptions like the sanguineus, have tubular flowers, assembled in hanging, much decorative, umbrellas.

They love the mid-shade, and the evergreen, such as the brachyscyphus or the herrei, are usually easier to cultivate.

The breviflorus, with its bright yellow flowers, and the Fire lily (Cyrtanthus falcatus), growing in summer, are also advisable, but there are also “difficult” plants, such as the spiralis, which require particular soils, or even a fire for blooming.

The gender Clivia has only 4 rhizome and evergreen species.

Beyond the yellow variety of the miniata, still unknown in Europe, also the nobilis would deserve a larger diffusion, with its cosy red-orange bells, with green apex, which often appear again in Autumn, after the rich May blossoming.

The Crinum, with the large corollas, white, pink, purple, or changing with the time, have about 130 species, mostly African, spread also in Asia and America.

Usually, they need full sun, abundant watering and manuring adequate to the size during the vegetative period.

The species which grow up for months in flooded soils, tolerate, without any problem, the stagnant waters.

The phenomenon, in violent contrast with the concept of bulbous plants, might find an explanation with a sudden change of climate in the arid habitats where they lived, not yet followed, due to the much longer timings of the biological evolution, by the regression of the bulb.

And this would confirm what nursery keepers see incessantly in cultivation: the extreme adaptability of the bulbous plants, capable to tolerate, much more than other plants, conditions often very different from those of their original habitat.

From Mexico, for collectors’ enjoyment, comes another odd species, the Aztec Lily (Sprekelia formosissima), with typical red “birdy” flowers, with a diameter of 10 cm, which open in April-May, before the leaves.

In the Mediterranean area, where the temperature never drops below 7-10 °C, this plant can pass the winter in the open air without any problem.

The gender Alstroemeria, well known to the lovers of bouquets, has about fifty South American species, mostly coming from Chile, which have originated various horticultural hybrids.

They grow up well in the open land, in sheltered and shaded places, but, often, they cannot stand the frost.

The blossoming, in spring an summer, is very much copious, and the leaves fall in Autumn, when the plant shelters in a sort of a tuber.

The same can be said for the Bomarea multiflora, a creeping Amaryllidacea of large size, which every year starts from zero, reaching the 2-3 metres of height.

South American, similar to the gender Alstroemeria, requires big amounts of fertilizer during the intense vegetative period.

The Zephyranthes, similar to big Crocus form a group of more than 65 American species, spread from Texas to Argentina, rather common in the nurseries.

They grow up like mushrooms, and make lively coloured spots on the lawns.

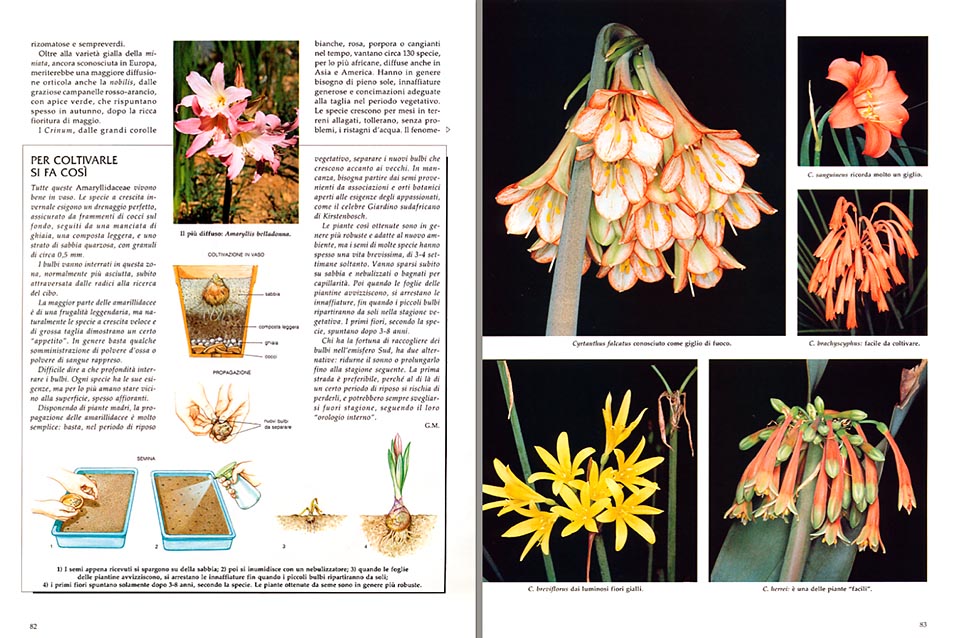

All the Amaryllidaceae live quite well in pots.

A kind of cultivation, which, besides limiting infection risks, permits to shelter them easily, depending on the climates, from the rainy or cold weather.

The species growing in winter require a perfect drainage, provided by fragments of earthen pots in the bottom, followed by a handful of gravel, a light compound, and a layer of quartzy sand, with granules of about 0.5 mm, which spread the sunlight, increasing in the meantime the evaporation.

The bulbs must be interred in this place, normally drier, which is pierced at once by the roots looking for food.

The most part of Amaryllidaceae is very thrifty, but the growing fast and big sized species, reveal a certain “appetite”.

We must be prudent with the nitrogen, and normally, it is sufficient to effect a few administrations of powder of bones or powder of curdled blood.

Generally speaking, it is difficult to say to which depth the bulbs must be interred.

Each species has its own exigencies, but most of them love to stay close to the surface, often coming up to the same.

If we dispose of mother plants, the spreading of Amaryllidaceae is very simple: it is sufficient, during the period of vegetative rest, to detach the new bulbs which grow up close to the old ones.

If these are not available, in order to set up a collection, we have to begin from the seeds coming from associations or botanical gardens open to the requirements of lovers, such as the famous South African Garden of Kirstenbosch.

The plants obtained in this way are usually more robust and suitable for the new habitat, but the seeds of many species, when they do not already germinate on the inflorescence, do have often a very short life, 3-4 weeks only.

They must be disseminated at once, as soon as received, on some sand and nebulized or watered by capillarity.

Later on, when the leaves of the plants fade, watering must be stopped, till when the small bulbs will start by themselves in the vegetative season.

The first flowers, depending on the species, come out after 3-8 years.

He who has the luck of picking up bulbs in the southern hemisphere, has two options: to reduce their sleep or to prolong it till the following season.

The first is preferable, because, beyond a certain time of rest, we risk to lose them, and they might always wake up out of season, following their “internal clock”, with catastrophic results.

The best thing is to get them in the southern hemisphere when they are sleeping from 2-3 months, and push them immediately to germinate, even somewhat late, following the new seasons.

GARDENIA – 1990

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within the AMARYLLIDACEAE family please click here.